For me, of all the challenges the pandemic has presented, living in a flat without a garden or a balcony has been the toughest. In many senses I’m lucky – I live alone and near a large park, which has stayed open during the crisis – but for many a lack of outside space coupled with the restricted use of public space has proved unbearable. The UK is experiencing ‘a tale of two lockdowns’ to borrow the words of writer Lynsey Hanley, whose recent article on the divided experience of Covid-19, struck a chord with many.

For Hanley, ‘space – how it’s apportioned, how it’s governed, how it’s made available to some and denied to others – is always political’, and our society now splits according to our spatial assets: those with gardens and spacious homes (sometimes with another tucked away in the countryside, or by the sea) with room to work from home; and those, typically the urban working class, living cheek by jowl in flats with little room to live, let alone work.

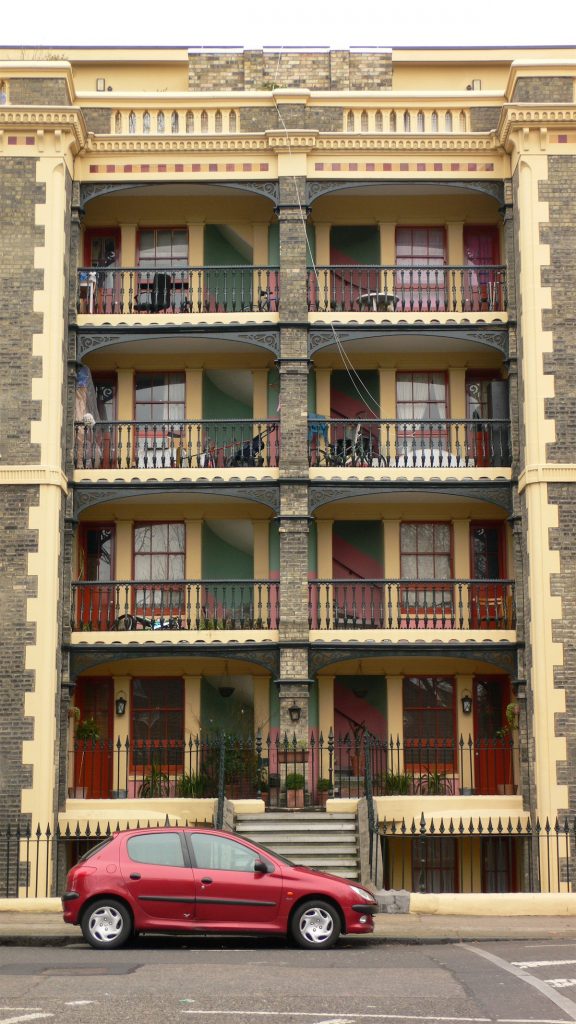

The balcony, then, has taken on a new, potent meaning. This cantilevered patch of private/public outdoor space has become a desirable and reactivated middle ground in the time of crisis. And it provides a new perch for many forms of everyday activities usually conducted elsewhere: from exercising and dancing to early evening civic gathering space. What we are seeing is a kind of vertical passeggiata (the Italian evening ritual of taking a post-dinner stroll), if you will, a necessary-yet-entertaining urban spectacle when life on the street has all but disappeared. Wandering the streets of London on my daily hour of government-sanctioned exercise I became captivated with balcony life. In Britain we tend not to use balconies as fulsomely as we might. We do sit outside on compact garden furniture or the occasional deck chair, but most urban balconies are used as an extra outdoor room. Here, we park our bikes, hang out the washing or store boxes that won’t fit inside; sometimes we create mini-oases, boutique gardens of delight, that provide a pleasant green prospect from one’s window – but not one to sit within. Occasionally you see people spilling out from a party to smoke a cigarette or sitting reading a book, soaking up the sun.

The balcony as a new and necessary site of public daily life has been thrilling and heart-warming to see: impromptu hi-energy exercise sessions, neighbours nattering or cheering the NHS from above and below; and, in the case of the Italians who entered lockdown earlier than the UK, serenading one another from Juliet balconies. La passeggiata is a beautiful Italian tradition, where residents take a leisurely stroll through their central town square, stopping to talk to friends or for aperitivo before dinner. It comes as no surprise, then, that one of the most delightful ad hoc inventions of the pandemic is the balcony toasting stick. This simple length of bamboo is fitted with a hoop at one end into which one slots a flute of Prosecco. The drinking-rod is then cast out over the balcony to bid ‘salute!’ to neighbours who cast their own rods from across the narrow street. Happy hour continues in the pandemic by any means necessary. (The safety of this method, and potential transmission of virus, has not been tested.)

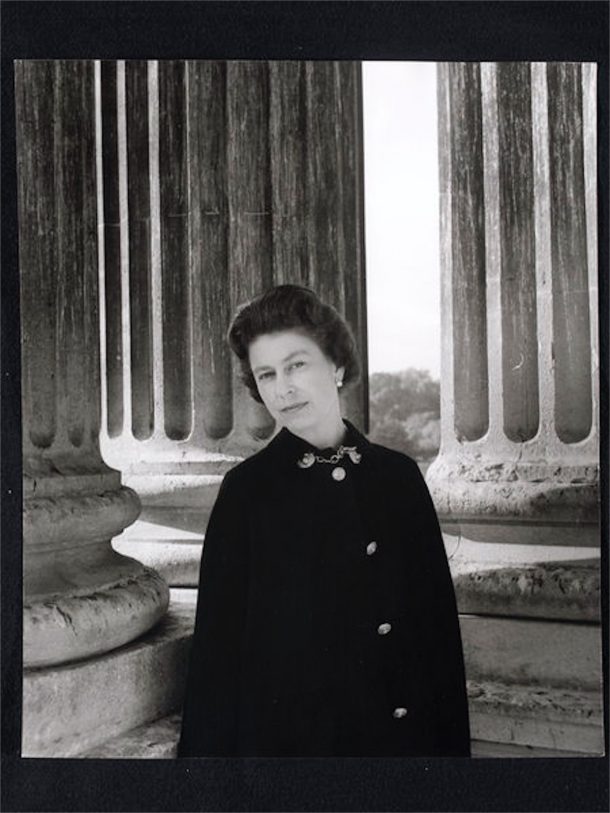

The balcony has many architectural forms and uses depending on where you are in the world and when the building was made or updated; and the V&A’s collection is a treasure trove of balcony histories – as built, or as captured in artistic imagination. In one of Cecil Beaton’s many photoshoots of the British royal family throughout the 1950s and 1960s, he captures Queen Elizabeth II against the neoclassical grandeur of one of Buckingham Palace’s balconies.

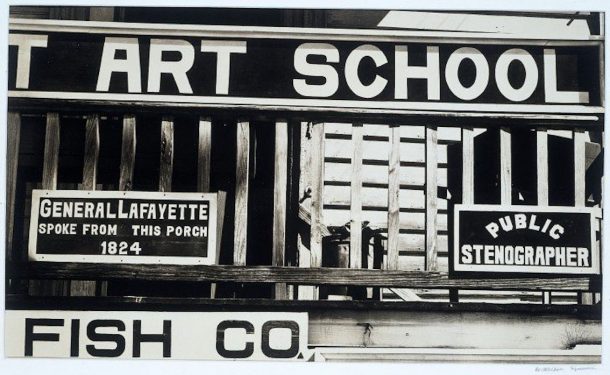

It is an intimate and surprising portrait, distinct from the prevalent, mediatised image of the royal family formally greeting their public from the Palace’s splendid central, east-facing balcony. In contrast, Walker Evans, the great photographer and chronicler of American life spent two years documenting rural communities of the South for the Farm Securities Administration (FSA) as part of the New Deal programme to combat poverty in Depression-era America. Evans’ tightly-framed shot of hand-painted signs hung on a balcony is testament to his interest in the language of vernacular architecture and roadside signs, but also tells us another story about the role of the balcony as platform for oration; here, the sign proclaims, General Lafayette spoke in 1824. As we face a global recession, the documentary photographic works of Evans and his peers such as Dorothea Lange feel pertinent.

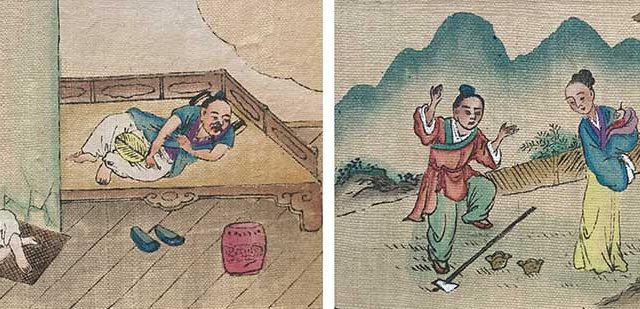

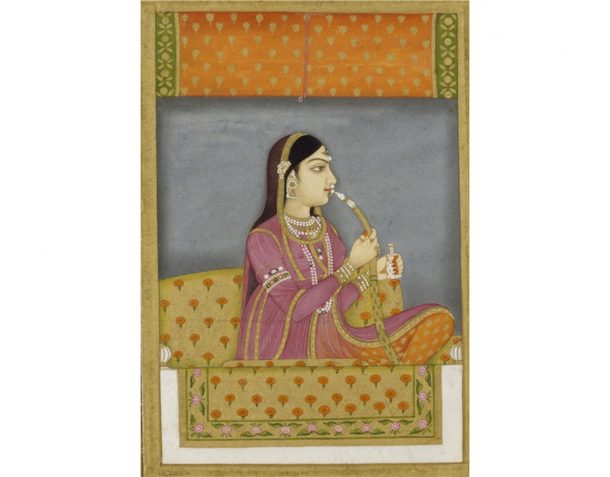

Going back further in time, this exquisite Mughal Empire painting made in Lucknow around 1750 depicts an elegant, bejewelled woman smoking a huqqa while sitting on a balcony lavishly hung with decorative, patterned fabrics. A simple activity played out on the most visually sumptuous of environments.

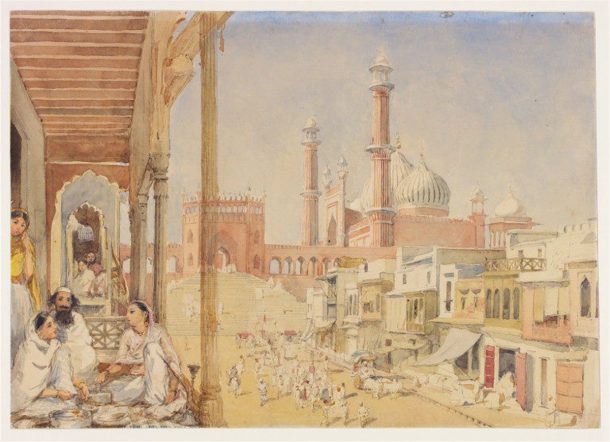

Staying in India but some hundred years later, this watercolour by English artist William Carpenter shows a view of India’s largest mosque, the Jami Masjid in Delhi, as seen from the carved wooden balcony of a grand house, where members of the Muslim household are taking refreshments. Although very different in style, composition and technique, both tell us much about building design, furnishings and lives lived in this semi-outdoors.

In Europe, the fashion for cast and wrought iron building elements, used particularly for balconies, grew in the second half of the 18th century as the Industrial Revolution increased the possibilities of working with these materials. The V&A’s collection includes a wide variety of decorative balcony fronts, panels and railings, from Robert Adam’s inventive use of cast iron for balconies at the Adelphi development by London’s River Thames, built in the late 1800s, to a recent example by jeweller Shaun Leane, whose striking design for an apartment block in Kensington sees bronze leaves and branches creeping across the building façade and balcony railings to dramatic effect.

The balcony, when you look closely, is rich in design history and full of life. Let’s hope post-pandemic urban living continues to play out on the balcony as much as the street.

Further Reading

Lockdown has laid bare Britain’s class divide, Lynsey Hanley, the Guardian, 7 April 2020

‘Balcony churches: Kenyans find new ways to worship in lockdown‘, Neha Wadekar, The Guardian, 29 June 2020.