This is a moment of deep crisis for civilised values on the continent of Europe. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has revealed where the awful trajectory of ethno-nationalism and political autarky can take even sophisticated polities. Yet, at the same time, in those very European cities taking in Ukrainian refugees, there is a tangible crisis of confidence as to the nature of the European values of multi-culturalism, the public sphere, and even democracy itself. Unsurprisingly, art, culture and museums are part of this fraught conversation.

How in an age of social justice, decolonization, and anti-racism, should a museum fulfil its function in a credible and purposeful manner?

Enlightenment foundations

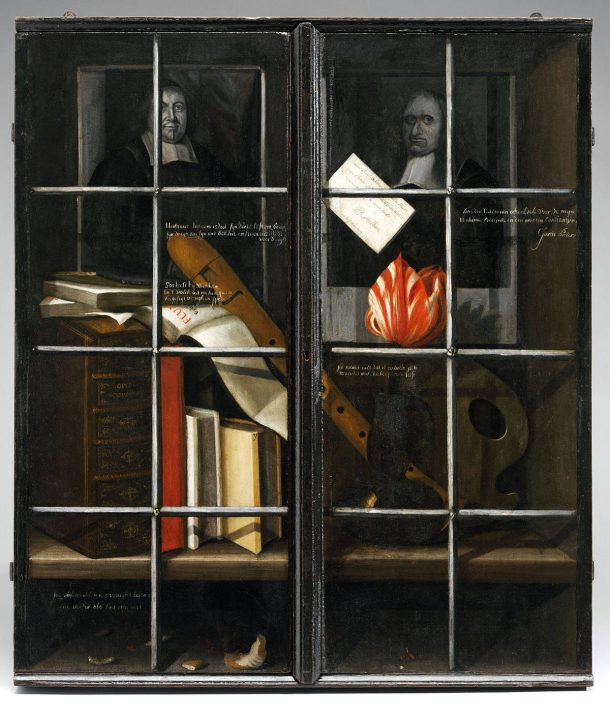

In Paris, London and Berlin, the age of Enlightenment – of reason and knowledge; the challenging of church and monarchy – found its form in the development of public museums.

The Enlightenment museum was a public space dedicated to the diffusion of useful knowledge, whose central advance from the medieval treasuries of the Roman Catholic Church or Wunderkammer of the Renaissance princes was an accessible taxonomy of the natural and artistic world with a hierarchy of understanding. The founding mission of the British Museum and the Louvre was to nurture an educated citizenry towards a more democratic culture of public education.

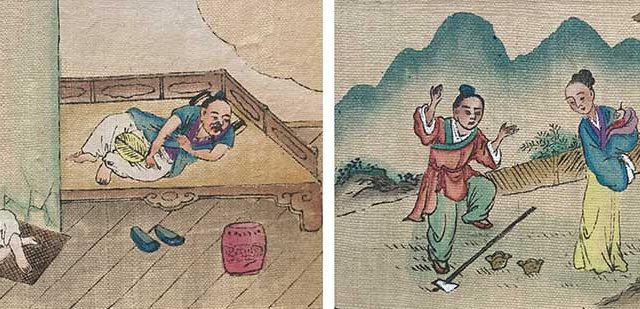

In Berlin, the university and museums founded by the Humboldt brothers on an ideal of Bildung (or ‘self-formation’) followed a similar trajectory. But it was always assumed that it was European knowledge that brought civilisation, progress and prosperity. GWF Hegel, in his Philosophy of Mind, suggested that only those people who were able to establish a state could be regarded as part of historical progress. ‘A nation with no state formation … has, strictly speaking, no history – like the nations which existed before the rise of states and others which still exist in a condition of savagery.’ This provided the intellectual underpinning for Marx and Engels’s philosophy of non-historic peoples, ripe to be swept aside by the tide of socialist progress. ‘Indian society has no history at all, at least no known history,’ Karl Marx wrote of south Asia. ‘What we call its history, is but the history of the successive intruders who founded their empires on the passive basis of that unresisting and unchanging society.’

This racist, Enlightenment conviction in European superiority shaped the construction of knowledge within the public museum. As Gus Casely-Hayford eloquently explains, ‘These men who defined the Enlightenment … looked upon Africa, a well-populated and varied-cultured continent, and saw in its peoples nothing – a void, a cultural tabula rasa – silence. It made colonialism, and the imposition of Western cultural norms, seem like a kindness’. One of the results of the Black Lives Matter movement has been a necessary public interrogation of the racial and cultural biases within museums’ collections, curatorial approach, and management.

Enlightenment in an age of social justice

So, the challenge for museum leadership is to unpick such toxic legacies and then seek to re-imagine the mission of the Enlightenment as an egalitarian, empowering, and transformative project.

First of all, museums should continue to provide a cultural and psychological resource for individuals to transcend inherited identities. The words of the former Getty Institute President James Cuno still resonate: ‘Without encyclopaedic museums, one risks a hardening of views about one’s own, particular culture as being pure, essential, and organic, something into which one is born.’ The material cultures that museums assemble speak to the inevitably tangled, multi-cultural and interconnected nature of our national identity and contemporary community. As Nicholas Thomas, Director of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in Cambridge, has written: ‘communities and individuals adopt and appropriate things; they may sense connection with things, and value things, that are not part of ‘their’ heritage in a reified cultural, ethnic or national sense.’ Museum collections have the capacity – and the calling – to take one beyond one’s self.

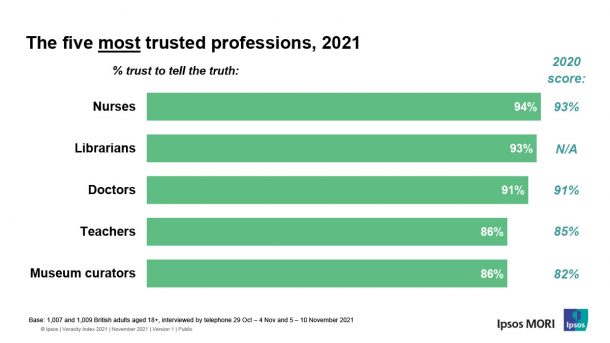

Secondly, they do so from a position of knowledge predicated upon an authoritative understanding of the collection, based upon the expertise of curators, conservators, archivists and scholars. Quite rightly, there is today a growing demand to open up the processes of museum interpretation to lived experience and co-curation. But that should be additive to the essential role of museum curation by experts in the field, whose authority remains widely admired. As so many institutions – from parliaments to media to religious bodies – face a decline in public trust, museums retain the confidence of the public and should be wary of any self-inflicted diminution of that strength.

The public museum of the Enlightenment came into being alongside the ‘public sphere.’ Today, the effects of political division, social media righteousness, the collapse of mass media and rise of algorithmic determinism have reduced the space for meaningful, engaged dialogue. This has helped to undermine the fabric of democracy and ‘public opinion’ as an autonomous and legitimate political entity. I believe our exhibitions, galleries, and civic spaces are part of the ecology of democracy and we need to ensure we are properly open to all citizens, of all colours and creeds, who feel they and their families belong here.

Finally, we need to move from the Universal Museum of the Enlightenment to the Cosmopolitan Museum of the 21st century. The racism of the Enlightenment needs to be replaced by a much richer understanding of how the construction of European identity was always a global endeavour. This necessitates a continued reckoning with the imperial and colonial past and, with it, new strategies around restitution and repatriation based on reciprocity, humility, and shared professional endeavour with colleagues in the Global South. The post-war hierarchies must be dismantled to shape a truly cosmopolitan public sphere.

That is the modern calling of the Enlightenment – which endowed so many superb cultural institutions that have, in turn, transformed so many lives over the years. It still matters. Because the alternative to enlightenment is darkness and Terror, and it is there for us all to see in the bombed-out theatres of Mariupol and ruins of Kharkiv.