This post is part of a series called ‘Value Debates’, which highlight objects from the V&A Collection, some of which will appear in ‘Values of Design’, the inaugural exhibition for the V&A Gallery at Design Society. In each post, we will look at objects which propose a different way of addressing a certain value, and what that says about design. This week we look at design’s role in the distribution of goods.

Design has long struggled with the question of how to get goods to the people they are meant to serve. You can make the greatest product in the world, but if it can’t reach a market, what use is it? Distribution, for that very reason, is often at the core of any design strategy. Such considerations stretch back to the early days of global trade and were especially pronounced when markets opened up to Asia in the 17th century, as Western demand for Asian craft objects boomed. Porcelain and lacquer were especially sought after and – because their production techniques were unknown in the West – a huge export economy grew. For the West, there were two problems to this new bourgeoning economy. First: shipping was expensive, driving up the price of goods; and second: local manufacturers were losing out to their foreign competitors. The result was a flurry of activity in researching new ways to imitate and recreate these techniques. Entire economies grew from imitations, such as delftware for porcelain, and japanning for Asian lacquer, in an attempt to keep profits local and shipping distances short.

This hall chair addresses the problem from a different angle. Made in the early 18th century, the backboard and seat-board were first lacquered in China, then shipped to Britain, where the legs were made and attached. The boards were essentially ‘flat-packed’ to save room and cost on the voyage to England, preceding by nearly 250 years the flat-packing phenomenon popularised by IKEA in the 20th century.

Indeed, flat-packing is a common design strategy to address the distribution problem. In the 1950s, American designer Isamu Noguchi, for example, found inspiration in Japanese paper lanterns and began to produce what he called ‘light sculptures’, using the same traditional materials and processes. Over the course of 30 years, Noguchi produced several iterations, pushing the sculptural possibilities of the technique to its limit. Despite creating dozens of different expressive shapes, all of his lanterns could be collapsed into a flat, highly compact form, aiding in their distribution and thus their popularity worldwide.

In 2011, Simon Berry put forward a design proposal for an even more urgent distribution problem: how to get vital anti-diarrhoea medication to young mothers and children in rural Africa. Having worked on public health issues in Africa for years, he was frustrated by the fact that remote places on the continent could get access to popular commercial products like Coca-Cola but not to life-saving medicine. His idea was to create medication packaging that could fit in the leftover space of Coca-Cola crates, piggybacking on the multinational corporation’s powerful distribution networks, and thus getting medicine to the people who needed it.

The distribution question in design has often focused on saving space: making products take up as little room as possible in the shipping process. With recent innovations in digital fabrication however, new initiatives are looking at how to get rid of distribution altogether. Opendesk, founded a few years ago in London, aims to completely change the way we design, make, and buy furniture by operating as a platform onto which designers can upload their designs. The designs are specifically made so that they can be cut by a CNC-router. Consumers who want to buy a design are sent a file and directed to a workshop in their respective locale, which then cuts the pieces and assembles it. Opendesk does not operate a factory, does not own stores, and does not ship any goods. It simply coordinates the sending of digital files to producers and consumers, with virtually no distribution involved.

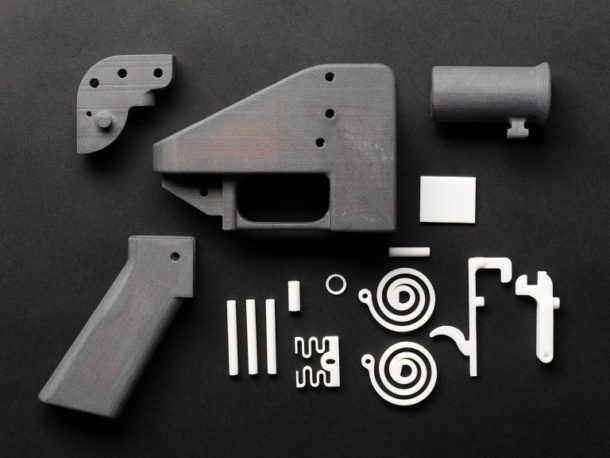

The idea that our goods can be distributed digitally and made locally is an exciting new territory for design. Once the realm of Star Trek fantasy, 3D-printers and other digital fabrication tools are becoming cheaper and more advanced, pushing designers to think about the possibilities they enable. At exactly the point when enthusiasm for 3D-printing was reaching a fever-pitch, however, one product came along which immediately questioned the kind of universal access that such tools promised. The Liberator, the brainchild of a Texan libertarian named Cody Wilson, was the world’s first 3D-printable firearm. In 2013, Wilson published the 3D files for the gun online for anyone to download. Virtually every country has some kind of control on the sale of firearms. The Liberator circumvented those controls by circumventing the distribution channels. Eventually, Wilson was ordered by the US-government to take down the files, but to a certain degree that damage was done. Thousands of people had already downloaded them.

In fact, regulators have been waging battle for years with the kind of access to illegal and counterfeit goods that the internet has enabled. In an ironic twist, many UX and UI designers are now charged with finding ways to control and limit access on the internet, rather than facilitate it. Our current situation prompts the question: how much access is too much access? Even with legally-sanctioned internet content, a certain malaise has set in amongst cultural critics who see a world of instant access (think online shopping, music and movie streaming, 24-hour news) as having negative mental and emotional consequences. While these critiques verge on the nostalgic, it is hard to deny the joy and satisfaction one gets from seeking out the hard-to-find, or owning something unique. In a world designed so that everything is immediately accessible to everyone all the time, rarity becomes the rarest commodity.