In a body of work spanning more than four decades, the Glasgow-based artist Roger Palmer has developed a sophisticated exploration of landscape in photography. Drawing on the legacies of 1960s land and conceptual art, his practice touches on questions of place, journeying, colonialism, migration, and the process of framing landscape as art. Here, for the V&A, he discusses a body of work made recently in South Africa.

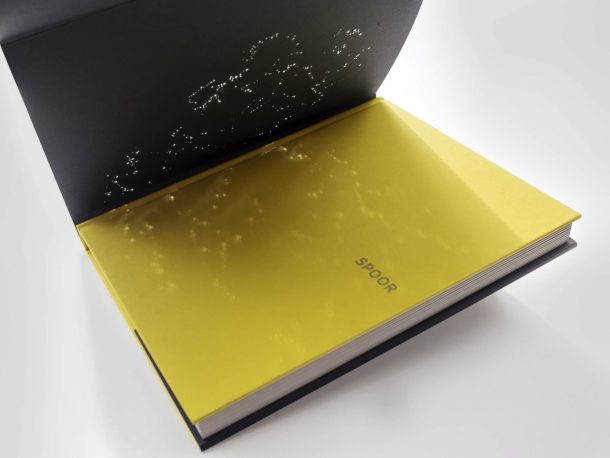

Your most recent publication is SPOOR (2019), in which you map and photograph mostly disused railway lines in South Africa. It’s an elliptical, compelling book – I find it hard to put down. How did the project come about?

The impetus to make new work is usually generated by several factors. In the case of SPOOR these included decades of observing the ways in which the landscapes of South Africa reveal the interwoven histories of settlers and rural migrants. In 2014, on a trip to the Eastern Cape, I spent a few minutes observing daily life at a disintegrating road and rail crossing. Photographs made there prompted my search for similar places. A picture made on the long drive back to Cape Town is included among the eighty-three images in SPOOR.

My approach to photography is inevitably influenced by the work of other artists. In addition to David Goldblatt’s subtle exposures of South Africa as a landscape of inequality, other key references for SPOOR include Lothar Baumgarten’s book, Carbon (1991), in which U.S. railways become sites of erasure in photographs and graphic insertions; Anselm Kiefer’s sculptural books, especially March Sand V (1977); and Jeff Wall’s The Crooked Path (1991).

The title of the book, SPOOR, is the track of a scent of a person or animal. It also refers in Afrikaans to railway. For me, there is also the confusion with the English word ‘spore’, which suggests a sense of dispersal. Such linguistic play is vital to your work – how does it inform the structure of the book?

SPOOR was the first and last of several titles I considered. I hoped its multiple references to different kinds of tracks would activate key photographic themes of the project but I had initial concerns about the visual appearance of a double ‘O’. ‘Spoor’ also serves the map sections of the book, as might ‘spore’, in that place names are dispersed throughout its chapters. Some names have a resonance that outweighs their significance as places – ‘Confidence’ and ‘Mirage’ are little more than trackside signs. Others, such as ‘Caledon’ or ‘Dordrecht’, have obvious colonial references.

A sense of process and location are central to your photography. Can you describe the mapping and journeying that shaped this book?

I rented cars at various South African airports with the intention of following cross-country rail routes. Journeys would last between five and fourteen days, with shorter trips near my Cape Town base. As usual I worked in a haphazard way, stopping frequently and accumulating images, most of which would be discarded.

As I wanted to include maps as part of SPOOR, but not maps that identify my cross-country routes, I devised a structure in which paginated sequences of pictures assumed precedence over particular journeys. Ten such sequences, each of eight or nine images, are interspersed by map pages of a different colour and weight.

On dark blue double-page spreads, silver place names are positioned according to their locations on an otherwise absent map of South Africa; each distribution being determined by the sequence of pictures that follows. I was thinking of night and day, with configurations of place names on dark pages followed by corresponding groups of daylight images on white paper.

The final pair of blue pages contain over 550 different sizes of silver spots resembling a star map. The dots mark all places where I can recall stopping to make pictures. This same distribution is echoed in the dust jacket with its laser-cut holes which was my publisher’s brilliant idea.

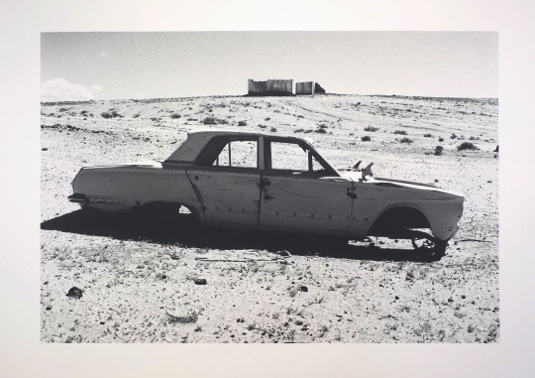

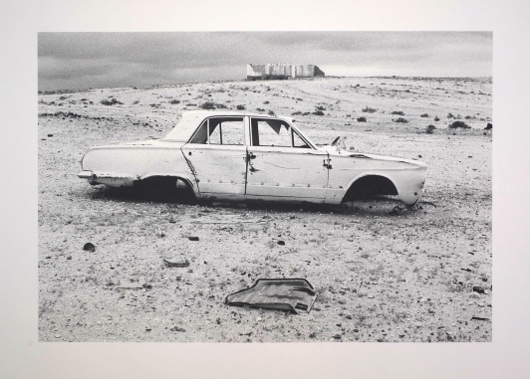

The building of the railways in South Africa is linked closely to mining and the expansion of settler colonialism; also to the migration of black labour, either by train or just as often on foot along the tracks. These are photographs of an industrial trace with a very loaded history.

Many South Africans’ daily travel is in overloaded combi (minibus) taxis or on foot. Twenty-first century rail traffic is concentrated around major cities, or serves mines, forestry, grain elevators, and tourism.

The legacy of apartheid is still evident in the layout of rural South African towns. Derelict stations and disused tracks are often located between what were once exclusively white towns – grids of broad streets, single storey houses, municipal and retail facilities – and the more densely populated townships a couple of kilometres away. As a consequence, many railways now serve as busy footpaths between township and town, home and work.

My interest is in the way that this once optimistic rail infrastructure maintains a faded, subliminal presence in contemporary South African landscapes. A sense of failure is balanced by adaptation, as articulated by a sign scrawled on a battered catering caravan which might once have read ‘ALWAYS INVAL[U]ABLE HERE’.

And in comparison with your earlier work there are many more people in these photographs, evoking this experience of migration. At the same time, your evident distance from them in the image is significant.

If all my photographic work references human activity in the landscape, my periodic use of a digital camera in recent years has enabled me to include people in ways that don’t seem possible with film photography. In SPOOR, figures are sometimes visible at a distance. Their first inclusion was something of an accident. Having waited for some time at a busy crossing I eventually made an image that included four people negotiating their way through a broken trackside fence – a picture that I recognised to be of greater interest than I initially expected.

Keeping my distance is primarily out of respect: I am always aware of my presence as an intruder and doubtless a brief source of curiosity for many. I enjoy the occasional good conversation, and have endured one or two instances of threat, but have no interest in featuring such events in my work.

For me, SPOOR has strong echoes of the work of the American land artist, Robert Smithson, particularly his 1967 essay ‘A Tour of the Monuments of Passaic, New Jersey’. That, too, is an account of a journey, albeit focused less on beauty in the landscape than industrial obsolescence. I’m wondering how Smithson’s anti-romantic conception of landscape, now more than 50 years old, resonates for you today?

A bus takes Smithson from Manhattan to Passaic where he writes about and photographs ‘monuments’ as evidence of industrial entropy along the Passaic River. This essay has been of lasting importance for me in that I’m repeatedly drawn to landscapes that reveal evidence of social change through visible layers of decay. My response has been to pursue a quotidian archaeology using (often obsolete) photography, sometimes in conjunction with other media.

In 2011, I made a 30-day journey across the United States between sites of two key works by Smithson. Beginning in Passaic N.J., I traced a spiral on a map that echoed the shape of Smithson’s Spiral Jetty, my eventual destination on the Great Salt Lake in Utah. The resulting project, Jetty, is an analogue photographic diary of a month on the road that makes several oblique references to Smithson’s oeuvre.

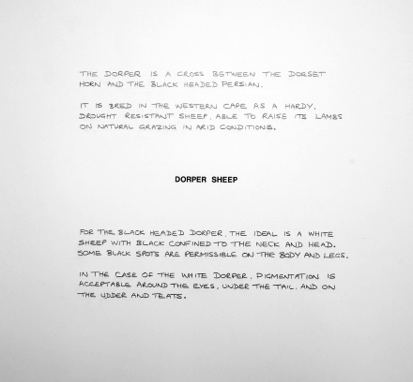

Finally, we have an early work by you in the collection, a triptych from your series Precious Metals made in South Africa in 1985. It’s a fascinating and important work, both in terms of the problem of representing in photographs the racialised landscape of apartheid South Africa, but also doing so as an outsider. The connection with SPOOR, spanning 35 years, seems very strong.

I first visited South Africa in the late apartheid era – a time of intense social unrest and police brutality. British media images inevitably focused on protest marches and accompanying state-sanctioned violence. At the time, the anti-apartheid movement was highly active. As an artist visitor, my attention to South Africa’s politics and landscape would need to be responsible and yet different. I spent a month as a houseguest in a so-called ‘Coloured’ township 300km north of Cape Town. Here and in a nearby abandoned village, I tentatively began to make photographs that reflected my unfamiliarity with the terrain.

Precious Metals was the unexpected product of this visit, my first work made beyond Britain and Ireland. The ten triptychs comprise silver gelatin prints and text panels that invite assessment of indigenous and colonial interactions through references to social structures, flora, fauna and climate. Thirty-five years after making the series, the politics of South Africa may have changed but the problems generated by colonialism are still very much in evidence.

Roger, many thanks. SPOOR is a remarkable book and we look forward to seeing your photographs at the V&A again soon.

FURTHER READING

Selected photo books by Roger Palmer

SPOOR, GOST Books, 2019

Jetty, Fotohof, 2014

Macao, Macau, Blackdog, 2014

Circulation, Fotohof, 2012

Overseas, Fotohof, 2004

‘Remarks on Colour’: Works from South Africa, 1985–1995, Oriel Mostyn and the Collins Gallery, 1995

Precious Metals, Cambridge Darkroom, 1986

Fascinating read and poignant images, the shadow lines across that dune!

Duncan

Delighted to read this and for many reasons.

Roger and I were both initial members of the (GPG) Glasgow Photography Group which we later founded and named Street Level …seems a lifetime ago.

Congrats to Roger (and yourself) all very encouraging and delighted to see this work.

Sending best

David