Study day celebrating nineteenth-century mosaics

The number of angels flying around shop windows across town seems to increase by the minute, as Christmas is approaching. I would argue that angels are always in season, if only you know where to look: apart from the V&A, of course, St Paul’s Cathedral is an excellent example. A particularly thoughtful specimen of their impressive angelic host has just become the ambassador for their over 100 nineteenth-century mosaics.

If you have yet to get to know this intriguing mosaic cycle, rejoice: St Paul’s Cathedral is launching an online catalogue and guidebook later this week. In addition, the free study day Glories in Gold and Glass: Mosaics and Ecclesiastical Art this Friday, 13 November 2015, will celebrate the mosaics at St Paul’s and the wider context of mosaic making from the mid-nineteenth century onwards: as one of the speakers, I will have the pleasure of giving an introduction to the cycle created by William Blake Richmond until 1904. There are still a couple of places left, so do register and join us for this day of mosaics celebration.

To get you into the mood here are some nineteenth-century mosaics in the Gilbert Collection, angels in (sometimes) gold and (always) glass included.

St Mark’s Basilica, Venice

Venetian mosaicists began to make glass mosaics from around a thousand years ago. The seventeenth-century mosaics on the façade of the basilica, and the stone angels on the finials were repeated in even smaller tesserae on this micromosaic in the Gilbert Collection.

St Peter’s Basilica, Rome

Venetian mosaicists introduced glass mosaics to Rome, and founded the Vatican Workshop. In the seventeenth-century the dome mosaics, visible at the top of Augusto Moglia’s micromosaic were created. Christopher Wren’s son alleged in his book Parentalia (1750) that his father had intended to decorate the dome of Saint Paul’s Cathedral in mosaics

as is nobly executed in the Cupola of St Peter’s in Rome, which strikes the Eye of the Beholder with a most magnificent and splendid Appearance; & which, without the lead Decay of Colours, is as lasting as Marble, or the Building itself. For this Purpose he had projected to have procured from Italy four of the most eminent Artists in that Profession; but as this Art was a great Novelty in England, and not generally apprehended, did not receive Encouragement it deserved. (Wren, Parentalia, p. 292)

The main church of Catholicism remained the benchmark for the decoration of St Paul’s Cathedral in London in the nineteenth-century: either as an example to follow, or as an approach that was entirely out of question.

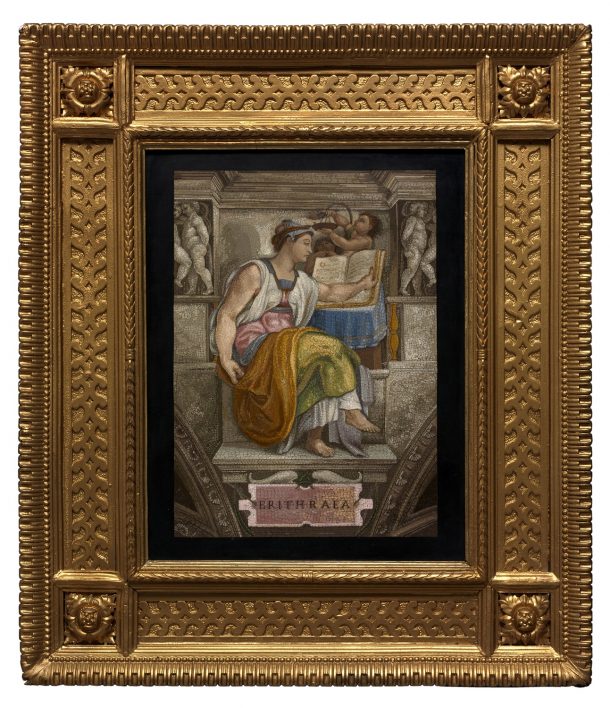

Sistine Chapel: Sibyl

Just as St Peter’s Basilica, Michelangelo’s famous fresco ceiling decoration of the Sistine Chapel, created between 1508 and 1512 became a source of inspiration for future mosaicists. This micromosaic copy of Michelangelo’s Erythrean Sibyl in the Sistine Chapel only measures 25.9×20.3cm. She is, more or less ably, supported by two putti attempting to light a lamp behind the Sibyl’s book. These toddler boys are wingless, and show that the classical motif of the putto (the Latin word putus means boy), not as angel, but rather as playful assistant or mere decorative element, was revived in Renaissance times.

Ancient heritage: putti

This putto is far removed from the gold-infused creations in the basilicas of Saint Mark’s and Saint Peter’s and later St Paul’s: rather than a Christian angel or simple putto he is a depiction of Amor, the ancient Roman god of love and (not only heavenly) desire. Made around 1800, the mosaic emulates the effect of an ancient marble relief in opaque glass. The piece will be on display shortly, in the V&A’s new Europe 1600-1815 galleries.

As this later micromosaic brooch shows, not only swans served Amor, stags were also in his employ. An inscription on the back reveals that the brooch was given to Elizabeth P. Pearson from my aunt A.S.B. 1843. While still drawing upon the same classical imagery, this mosaic takes 1st century AD Roman wall frescoes found in Herculaneum as point of departure: colour has once more returned to the mosaics. And even a bit of glitter appears to have been allowed, as the golden (rather than gold) border shows.