The ‘rediscovery’ of terracotta as architectural material in Britain goes back to the beginning of the nineteenth century. In this period different firms and individuals conducted experiments around the production of ‘artificial stone’. This was a material that artists could model like clay. However, at least in its early days, they used it to imitate stone. Eventually, around mid-century, the production of ornamental terracotta for architecture took on.

The Beginnings of ‘artificial stone’: ‘Coade Stone’

One of the most successful artificial stones was ‘Coade Stone’. It was produced in Lambeth (London) from 1769. It consisted of a body of fine modelled clay imitating natural stone. Coade stone lent itself to the production of garden ornaments (vases, statues etc.) and architectural details (fig. 1).

Other kinds of artificial stone entered the market over the first decades of the nineteenth century. They consisted of cement binding an aggregate. Examples of this material in use appear in a number of neoclassical buildings. For instance, one of the most impressive is St Pancras Church (1818-22) in London (fig. 2).

Architectural ceramic in Neogothic buildings: 1840es -1850es

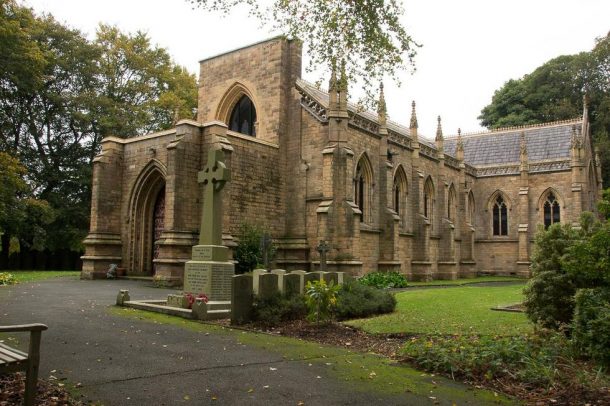

At the 1851 exhibition Messrs. Willock & Co, of Manchester, displayed a number of decorative elements for the home and architectural details in terracotta. They even showcased a complete model of a Gothic church decorated in terracotta. The material was employed, at this time, in churches around the country. Particularly rich are the area along the Welsh boarder and Lancashire (fig. 3).

In many of these buildings the use of terracotta was a means to keep costs down. Generally speaking, people disapproved of openly employing this material in connection with architectural styles that, historically, had not done so.

Terracotta and (neo) Romanesque and Renaissance Architecture: South Kensington

The South Kensington projects broke this ‘taboo’. Indeed Cole and Fowke wanted to recreate the feel of Italian architecture in a cost-effective way. Stylistically, they took inspiration from Renaissance architecture in Northern Italy. This used terracotta extensively. However, they applied this material also to the production of architectural elements inspired by Romanesque and Renaissance architecture originally built in stone.

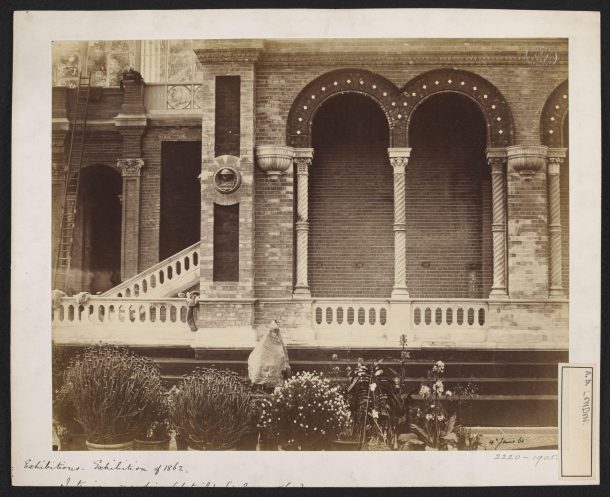

Together with Richard Redgrave, Sidney Smirke and Godfrey Sykes, Cole and Fowke experimented with terracotta for architectural decoration in South Kensington. Particularly, from 1858, in connection with the Royal Horticultural Gardens. This was an elaborate, Italianate garden of more than 80.000 m2 (almost 20 acres). It was between where the Albert Hall and the National History Museum now stand.

The twisted columns in the Horticultural Gardens (fig. 4) are made of terracotta. They are one example of the application of this material to the production of architectural elements that belong to a stone-based tradition. The main historical model that inspired them is the cloister of St John in the Lateran in Rome.

If you want to know more…

This post is an outcome of the Leverhulme Trust funded Project Designing the Future: Innovation and the Construction of the Royal Albert Hall. Read the full story of the Albert Hall’s construction in the forthcoming monograph The Royal Albert Hall: Building the Arts and Sciences.

To find out more about the Royal Albert Hall’s unique characteristics and background see the other posts connected to the project. These include an ongoing series on terracotta. Watch out for the next ‘episode’ coming out in August!