This blog is part of a series on Henry Cole’s travel diaries, three of which are in the V&A’s collections.

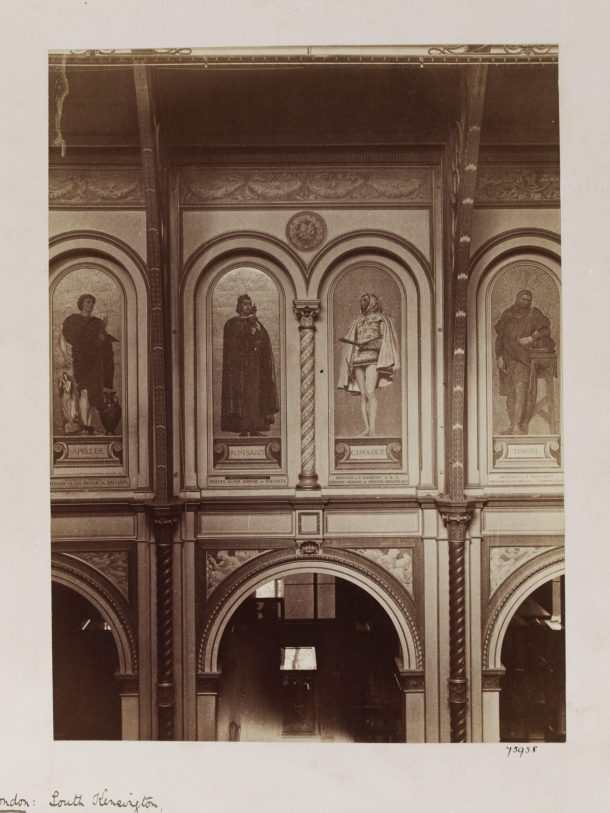

In the history of the V&A, no one looms quite so large as its first director, Sir Henry Cole. His memory is inscribed into the very fabric of the building, notably by means of a mosaic portrait on the landing of the Ceramic Staircase, installed in 1878 to pay homage to the contribution he made to the formation of the South Kensington Museum.

As part of his official duties, Cole travelled extensively around Europe, documenting these voyages by means of detailed handwritten accounts. Previous blog posts in this series have offered insight into his diplomatic mission in Vienna in 1851 and the quest for reproductions in France and Germany in 1863. We’re picking up the thread of this story five years later, as the tireless Cole embarks on yet another trip: this time going on a nine-and-a-half-week tour around Italy in the company of Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Scott.

‘To Palermo and back’

From an institutional perspective, the purpose of the 1868 journey was twofold: to prepare ‘a plan for illustrating in the South Kensington Museum the history of the art of mosaic working’ and to ‘supply by the illustrations thus obtained part of the decorations of the new buildings’. It was only appropriate, then, that Cole should be accompanied by Scott, the director and designer of the new buildings.

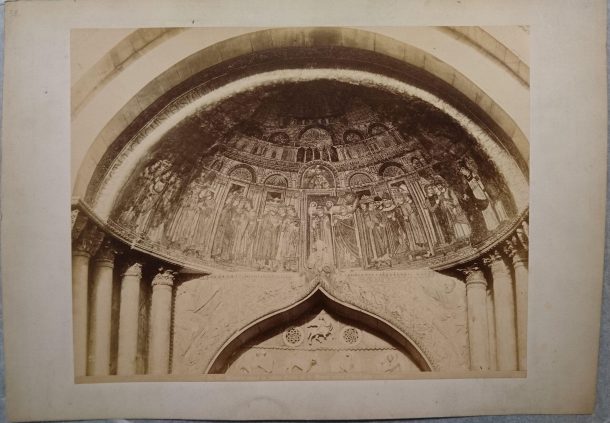

As Cole and Scott were on the lookout for examples of mosaics, Italy was an obvious choice of destination. A paper presented at a meeting of the Royal Institute of British Architects by Sir Austen Henry Layard in 1868 is evocative of the late-Victorian perception of Italy in this regard. According to Layard, a seasoned globetrotter himself, it afforded ‘the best school for the investigation of the subject’. He also singled out four examples that he ‘particularly’ recommended for ‘imitation’ in Britain: the Basilica of San Marco in Venice, Monreale Cathedral, the Capella Palatina in Palermo, and the basilicas in Ravenna, all of which formed part of Cole and Scott’s itinerary. Layard himself, as we will see, accompanied Cole and Scott on their visit to San Marco, which he considered to be ‘the most perfect example of internal decoration in the world’.

Not only did Italy have a rich tradition of mosaic decoration, it was also leading the way in its European revival. This was spurred by Antonio Salviati, a former lawyer who had made it his life’s mission to reinvigorate the craft in Venice. Salviati established his first workshop in 1859. A year later, he met Layard, who became the firm’s champion and subsequently one of its British shareholders. The relationship with Layard proved extremely beneficial for Salviati, leading to several high-profile commissions, such as the Royal Mausoleum at Frogmore and the Albert Memorial. Salviati was also involved in producing mosaics for what became known as the ‘Kensington Valhalla’ – a series of portraits of celebrated artists commissioned by Cole between 1862 and 1871 to decorate the South Court of the Museum.

The diary

Cole and Scott’s journey is recorded in a travel diary, which is a curious jumble of handwritten notes, leaves torn out of a sketchbook, and printed reports of Cole and Scott’s findings appended at the very end. As an object, it is also somewhat deceptive: although the title page introduces Cole as the author, very little of the diary has actually been written by him.

Cole’s notes make up a mere twenty-one pages and offer a very fragmentary account of the trip. The party had set off on 9 October 1868 and returned to London on 14 December. Out of these nine weeks, Cole’s section of the diary covers just fourteen days and ends abruptly on 19 November. Additionally, some of the later entries offer little to no information about the journey, consisting of brief remarks marking its progress, as well as to-do lists on which Cole ticks off tasks, such as picking up correspondence or ordering photographs.

Such sloppy record-keeping is unusual for Cole, who is otherwise a conscientious diarist, faithfully recording his day-to-day activities – which he did over the course of the trip in his daily diary, the transcript of which can be consulted in the National Art Library. As the journey went on, perhaps he decided it wasn’t worth keeping two separate accounts; or maybe the task of notetaking was simply delegated to Scott, whose records make up the bulk of the volume.

Scott, the unacknowledged author whose name is conspicuously absent from the front page, offers an exhaustive account of the pair’s tour around Italy, complete with an index itemising places of interest and notable works they had observed throughout their travels, as well as lists of objects to be copied in different media. Thus, reading the diary, we see the trip chiefly through Scott’s eyes. Even so, Cole’s presence is still asserted through frequent references to objects ‘H. C.’ considered worth copying or purchasing, which speaks to the immense personal influence he exerted over the shape of the Museum’s early collections.

Cole and Scott at San Marco

There are a few places in which Cole and Scott’s account overlap, making it possible to compare their distinct perspectives. The visit to San Marco, which they toured in the company of Layard, offers a compelling example. Cole’s notes, which consist of a list of mosaics it would be ‘desirable to consider the cost of executing’, suggest that his mind was set firmly on choosing the best examples to be copied. Scott’s account reveals that the process of selection was more collaborative than Cole lets on, with Layard playing the role of advisor, though Cole did not always ‘fancy’ the examples Layard proposed as ‘characteristic specimens’ for the Museum.

Scott himself seems to have been more interested in the technical side of mosaic application. As an officer of the Royal Engineers who had successfully experimented with the production of selenitic lime (a type of cement), he could bring an informed view to bear on the subject. At the time of their visit, the mosaics in San Marco were being repaired by Salviati’s firm, a process which Scott details in his notes. One of the things that Salviati prided himself on was the use of the original formula for the cements, which he managed to replicate by studying old Venetian chronicles; in Salviati’s view, this was the key to securing the mosaics in a way that would stand the test of time. Scott, however, was sceptical, considering the use of the original mortar to be ‘a mistake’.

The double perspective that the 1868 diary offers makes it unique in the corpus of Henry Cole’s travel writing, highlighting the importance of his interactions with figures such as Scott or Layard and raising questions about their potential influence. While Cole may have become virtually synonymous with the South Kensington Museum – and not without reason – behind his larger-than-life figure is a vast professional network, which further research into the diaries can help us uncover.

This blog post is part of a series reflecting on several travel diaries composed by Henry Cole in the second half of the nineteenth century and which are now being transcribed and contextualized by researchers and PhD students as part of the V&A’s Doctoral Placement programme.