At the height of the Covid-19 lockdown in April, I immersed in the online programme of Fashion Open Studio during Fashion Revolution Week, an annual event that brings together the global fashion industry to find ways to conserve and restore the environment – and advocate for safe, fair and dignified labour.

A lot of discussions around sustainable fashion have centred around materials – the types of textiles used, the methods and ethics of upcycling and recycling. Rightly so. We form direct, intimate relationships with a garment’s form and texture through our skin. Yet arguably, the colour of a garment is one of the most dominant components in both the design and manufacturing processes, and an unmissable feature even to the most utilitarian wearer. Colour also conveys multi-layered embedded cultural and psychological meanings. From an environmental angle, textile dyeing is one of the most polluting processes in manufacturing garments. It uses over 5 trillion litres of water per year, along with petrochemical dyes and up to 72 highly toxic chemicals – and accounts for around 20% of global industrial water pollution, rendering textile dyeing the second largest polluter of water after agriculture.

Reflecting on this I was inspired to revisit Simon Garfield’s Mauve: How One Man Invented a Color That Changed the World, which had been a rich source of reference during research for the V&A’s 2018 exhibition, Fashioned from Nature. It chronicles William Perkin’s serendipitous discovery of mauve in 1856, the world’s first mass-produced artificial dye (Perkin had intended to produce quinine from coal tar to treat malaria), and the subsequent unfolding of pivotal turning points across the worlds of medicine, industry and fashion.

His unexpected result revealed the cheap and easily applicable nature of coal tar-derived aniline dyes, and drove the development of a rainbow range of mass-produced synthetic dyes in the UK, as well as in Germany and Switzerland. These artificial dyes completely replaced traditional dyes derived from plants, insects and shellfish in mere decades (though the ethics behind animal-derived dyes remains controversial). The intense purple colour of fashionable dresses made from the late 1850s, such as this ruched dress (T.51&A-1922), owed much to the development of synthetic dyes belonging to the methyl violet and aniline blue families.

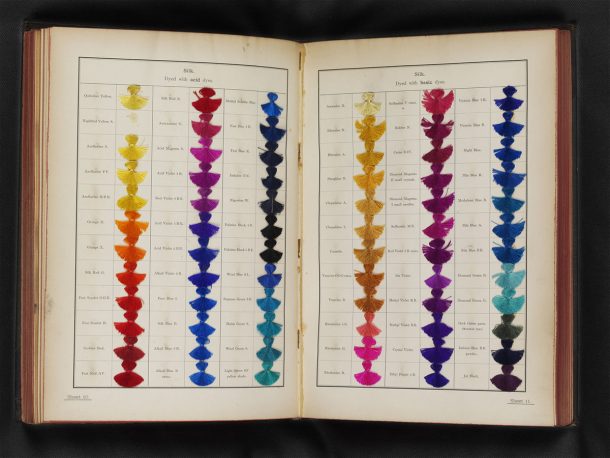

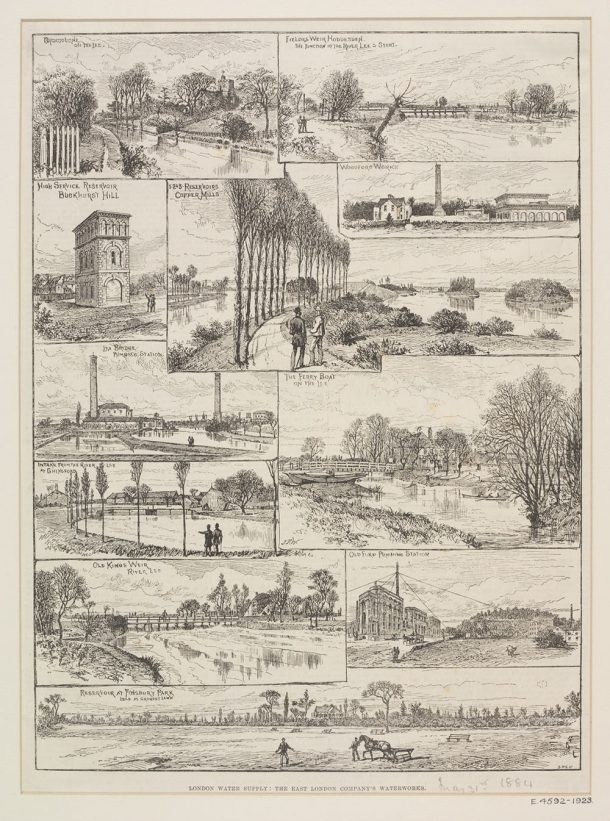

Coal tar derivatives were celebrated as an industrial miracle; dye books proudly titled as Coal Tar Colours were common to be found (T.180-1985). As Perkin’s Wembley dye factory discharged effluent into the Grand Union Canal, it notoriously turned London’s waterways changing colours of purple, green, violet and red. London is connected by waterways – although released locally in Wembley, the pollutants travelled along the canal as far as Birmingham. The ‘lucky’ invention of mauveine accelerated what is now a planetary disaster; Garfield’s book is aptly titled – Perkin did after all invent a colour that changed the world in unimaginable ways.

Having worked on the V&A East project for a year now, I could not help but notice the connection between Perkin’s story to the lineage of East London innovation in textile manufacturing.

What is believed to be the first English dye house was established in Bow in 1643 to make cochineal, the scarlet-coloured dye famously named Bow-Dye. Although his later factory was based in Wembley, Perkin, born and raised in Upper Shadwell, discovered mauvine on the top floor of his Cable Street home, in a laboratory he self-assembled when he was still a 16-year-old student at the Royal College of Chemistry. Thomas Keith, the Bethnal Green-based silk dyer known for his display at the Great Exhibition of 1851, was also a close collaborator. Brooke, Simpson and Spiller of Hackney Wick bought Perkin’s later works on alizarin in 1874 and, within a year, faced claims that the factory was causing irreversible environmental damages.

The magnitude of synthetic dyeing’s environmental damages appeared to be an already known fact in Perkin’s time, and has had a huge impact in his native East London.

Today, working in reverse, local East London makers and collectives are showing considerable effort in developing alternative dyeing systems in line with the principles of circular economy and reviving hand dyeing practice. For example, the Walthamstow-based organic raw denim maker, Blackhorse Lane Ateliers, is growing a plantation of Japanese indigo, as well as various plant fibres in their local Allotment close to the River Lea and the Tottenham Marshes. They also offer a lifetime repair policy that discourages fast fashion and grows the local maker community. The plant-dyed underwear brand Bedstraw and Madder hosts regular plant dye workshops in Hackney Wick to promote greater holistic health by ditching chemical dyes.

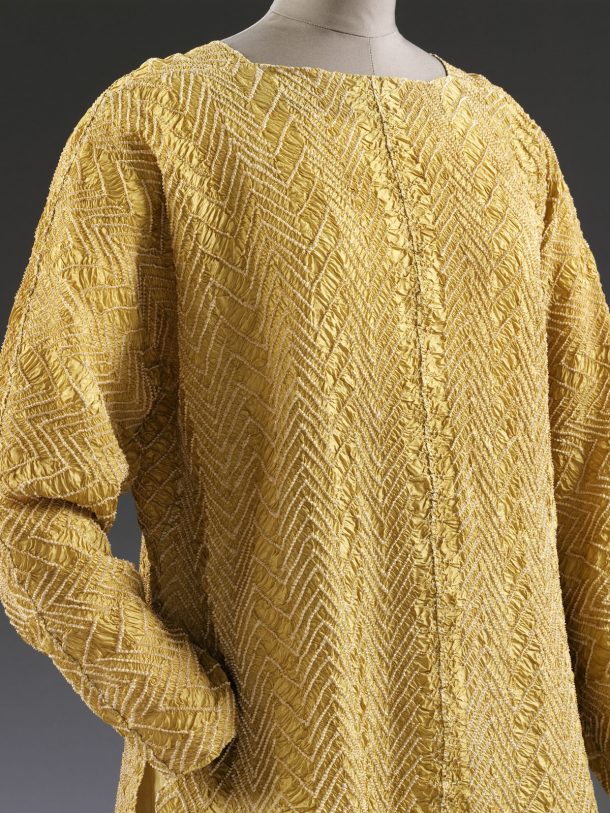

This conscious philosophy towards garment dyeing and production is, however, not new to the fashion world. Asha Sarabhai, married into the prominent industrialist Sarabhai family, an early advocate for natural dyeing and hand-woven fabrics in the face of polluting, substandard mass textile production in the 1970s. She started her much respected studio, Raag, in the city of Ahmadabad after completing her studies in social and political science at Cambridge University, and is still directing the workshop to this day. Sarabhai has been making thoughtful, minimalist garments at small scale for men and women of all ages, and her work has been much loved by those in the arts – her devotees include Robert Rauschenberg, Frank Stella, Frances Partridge, Terence Conran, Issey Miyake, Gita and Zubin Mehta, to name a few. Among the several dozens of Raag’s garments in the V&A collection, this vegetable-dyed mulberry silk blouse is the epitome of modernising traditional Indian dress, but also highlights the craftsmanship of traditional dyeing techniques (IS.13-1995). The Chevron design was realised by tie-dyeing in very fine knots, before washing out the red ochre that once drew out the pattern. The exquisite result demonstrates the beautiful marriage of skilled craft with environmental awareness.

As much as it is disheartening to learn that it was the lack of foresight, not of evidence, that led to exponential water pollution over the span of a century, I am encouraged by the hope injected by waves of creative design and making endeavours. If anything, the pandemic has reconnected many of us to the rhythm and ways of nature. The planet adapts, and if we stay attuned, informed and quick to action, we might be able to preserve our planet before climate change becomes irreversible by 2030.

good information regarding colors and dyes

I was fascinated to read this article as my family owned several dyeing businesses in Glasgow in the 1800s The main business was turkey red and was pretty much destroyed as soon as analine dyes became widespread, although I understand that turkey red dyed thread was still exported to Ireland for Irish linen tea towels until the second world war. I don’t think turkey red was unpolluting though, and I seem to remember that there were complaints relating to chemical pollution of the Clyde in the 1850s.