In the summer of 1962, Danny Lyon, a young history student from the University of Chicago, hitchhiked 390 miles south to Cairo, Illinois, to join the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the youth wing of the civil rights movement. Fired by the romantic spirit of the Beat poets, he took his camera with him – and immediately found himself documenting one of the most important struggles for democratic participation in the history of the United States. Lyon’s photographs would soon be circulated in their tens of thousands, icons of nonviolent resistance against a regime of brutal, sometimes murderous, white supremacy.

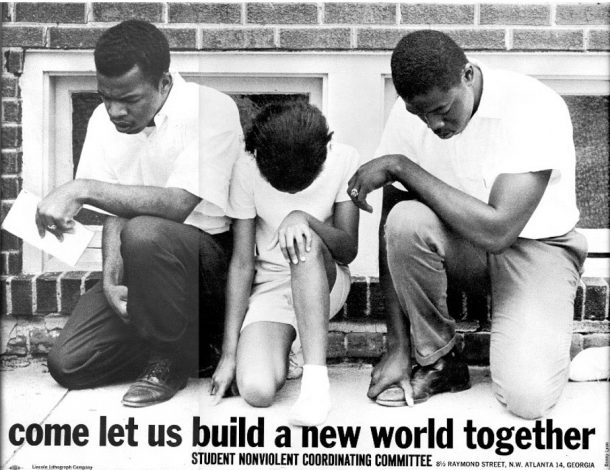

Lyon joined the SNCC as its needs for visual representation were becoming ever more apparent. One of his earliest photographs showed three demonstrators on bended knee praying in front of Cairo’s racially segregated swimming pool. The following year it was reproduced as a campaign poster under the slogan ‘come let us build a new world together’. On the left of the photograph was John Lewis, who has died recently at the age of 80, a leading figure within the civil rights movement and soon to become the SNCC’s chairman.

Since the SNCC’s founding in 1960, Lewis and his colleagues had been challenging day-in and day-out – through lunch counter sit-ins, freedom rides, demonstrations, and voter registration drives – the entrenched racial segregation of the American South. Rooted in a commitment to nonviolent civil disobedience it was unforgiving work, marked by the constant tension of deadly violence. Lyon, a Jew from Queens in New York, joined a small team of largely African American organisers, committed to an egalitarianism forged by Southern black communities in the shadow of slavery. With its members averaging just 21 years of age, the SNCC was close-knit and fiercely autonomous, a self-described ‘beloved community, a band of brothers and sisters, a circle of trust’.

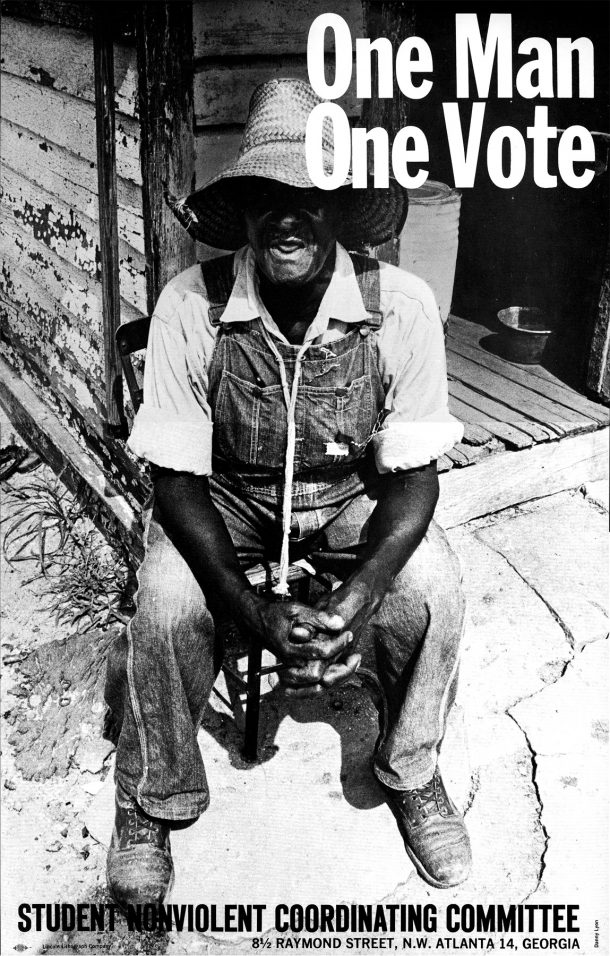

Printed in a run of 10,000, the poster sold at a dollar apiece, mainly to supporters in the north of the United States, a consciousness- and fund-raising tool. It quickly became an iconic image of the movement, defined by its anti-hierarchy and the determination with which the bowed figures grounded – literally through their poses and gestures – the moral authority of their actions. The message of the poster, deliberately stated in lowercase letters by the designer Mark Suckle, heralded the progressive interracial alliance that was then the ideology of the SNCC. This would eventually force the compliance of the Federal Government in the form of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. SNCC posters were history in the making.

E.2740-1995 © Image Victoria and Albert Museum, courtesy of Danny Lyon

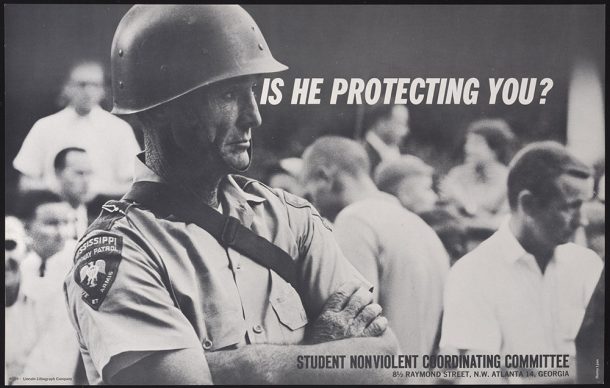

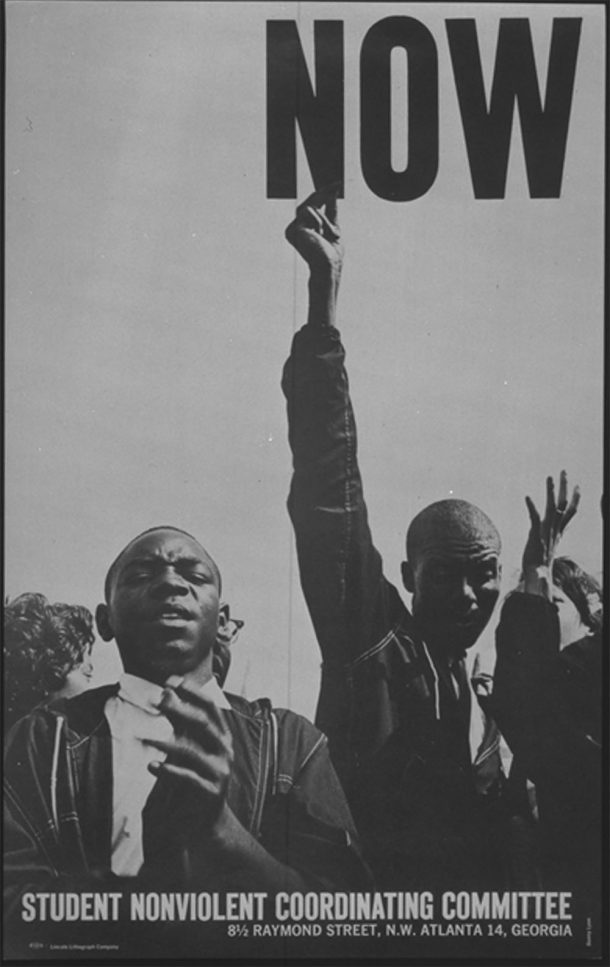

Lyon worked informally for the SNCC for a year while he finished his studies before becoming a full-time employee in June 1963. He travelled around the South according to the needs of the organisation’s Communications Department led by Julian Bond. Photography served multiple functions within the SNCC, directed at making the racism of the South visible. It supported the identity of the SNCC as a grassroots organisation, documented its protests, voter registration drives, and public meetings, as well as the violence targeted against activists. Photography also put a face on the organisation, aiding in the vital task of fundraising, especially among middle-class communities in the large northern cities. SNCC pamphlets, posters and photographs worked to counter racist coverage in the mainstream media. They spurred Federal intervention to protect African American human rights, a constant battle.

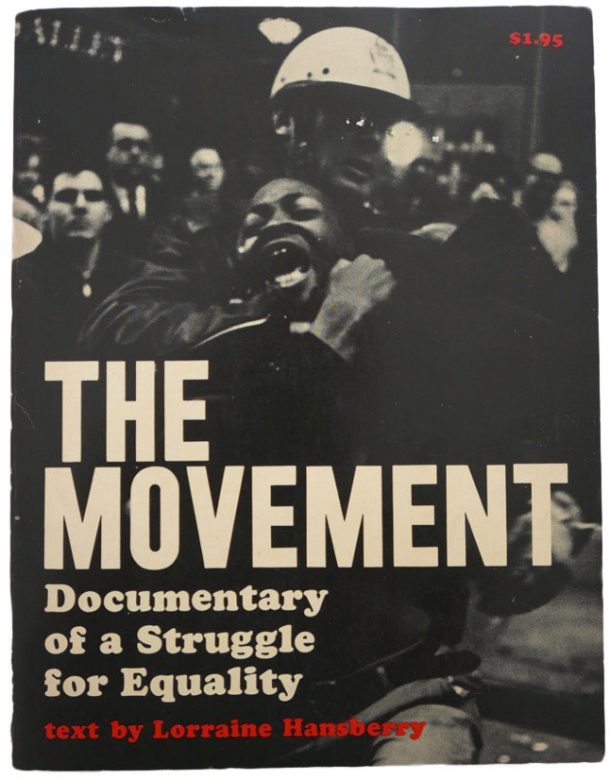

As it grew, the SNCC’s Communications Department built darkrooms throughout the South, recruited and trained photographers, the majority African American, and in 1964 instituted its own picture agency, SNCC Photo. It also produced exhibitions in 1965 and 1967, and published a superb photobook in a large print run, titled The Movement, written by the playwright, Lorraine Hansberry. The department also developed educational materials for use within the organisation and the communities it worked alongside. SNCC photography reframed African American resistance in a manner unprecedented in U.S. history.

Danny Lyon left the SNCC in the summer of 1964, reluctant to become further embroiled in its fraught internal politics. That year the SNCC staged a major voter registration drive, the Mississippi Freedom Summer, which involved an influx of volunteers into the organisation, undermining its discipline and close-knit ethos. Its youthful leaders came under intense pressure, especially in the wake of the historic reforms achieved in 1964 and 1965. Was the SNCC just a protest organisation, committed only to extending the civil rights struggle? Or should it tackle the pervasive economic and social inequalities that electoral legislation alone could never eradicate? Such questions inevitably had implications for the SNCC’s uses of photography.

John Lewis remained chairman of the SNCC until 1966, one of the most fearless among a cohort of deeply courageous men and women. He was arrested 40 times, took part in many of the SNCC’s defining protests, and was frequently beaten senseless by the police and racist vigilantes. He was the youngest speaker during the famous March on Washington in August 1963. As Lewis described it, his purpose was to ‘get into trouble, good trouble, necessary trouble’. He survived to repeat his message to a new generation of activists in June this year as, shortly before his death, he visited the Black Lives Matter Plaza in Washington, D.C.

Further reading

Danny Lyon, Memories of the Southern Civil Rights Movement, Twin Palms Publishers, 2010

John Lewis with Michael D’Orso, Walking with the Wind: A Memoir of the Movement, Simon & Schuster, 1998

Manning Marable, Race, Reform, and Rebellion: The Second Reconstruction in Black America, 1945–1990, University Press of Mississippi, 1991

Leigh Raiford, Imprisoned in a Luminous Glare: Photography and the African American Freedom Struggle, University of North Carolina Press, 2011

Iris Schmeisser, ‘Camera at the grassroots: the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the politics of visual representation’, in Patrick B. Miller, Therese Frey Steffen and Elisabeth Schäfer-Wünsche (eds.), The Civil Rights Movement Revisited: Critical Perspectives on the Struggle for Racial Equality in the United States, LIT, 2001, pp.105–25