Since 2017 the Gilbert Trust for the Arts has presented generous development opportunities for V&A staff to work on exciting projects. Remarkably, I was offered the last of these – an 18-month secondment to work on an exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA): Eternal Medium: Seeing the World in Stone.

The show is a collaboration between LACMA and the V&A (The Rosalinde & Arthur Gilbert Collection), curated by Rosie Mills, The Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert Foundation Associate Curator at LACMA. Visitors will see a spectacular exhibition of stone and other artefacts from the V&A’s and LACMA’s collections, and from several other lenders including The J. Paul Getty Trust and Fine Art Museums of San Francisco, on display in the Resnick Pavilion from now until 11 February 2024.

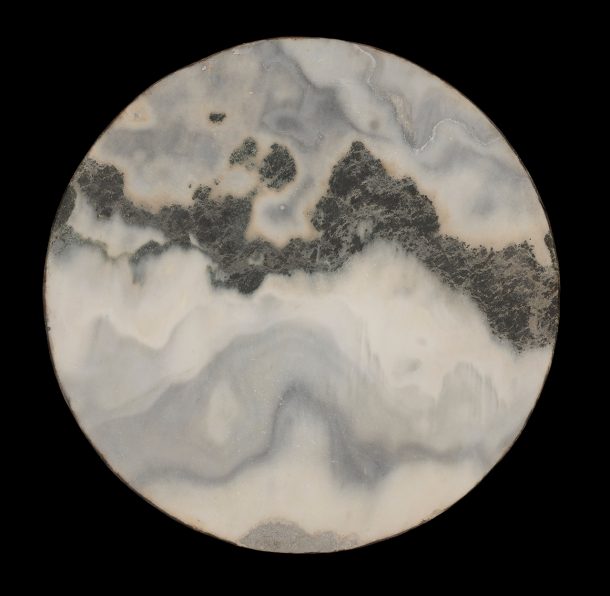

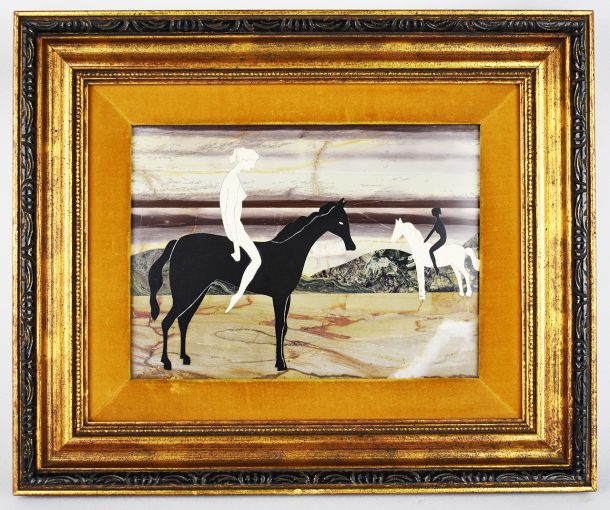

The show aims to bring together diverse works that utilise the natural features of stones, displaying them in the context of other mediums. The V&A is lending 49 objects, mainly from the Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert Collection. Among them are pieces of furniture decorated with hardstone mosaics set in ebony or ebonised wood, tabletops and pictures using hardstones and a vast number of snuff and decorative boxes embellished with gemstones and other ornamentations. The loan includes ceramics, ancient stone carvings, paintings on amethyst and works of art on paper.

These objects were originally collected by Sir Arthur Gilbert and his wife Rosalinde, British-born entrepreneurs and philanthropists, who supplied fashionable clothing, designed by Rosalinde, to London’s prestigious department stores. Relocating to Los Angeles in 1949, Arthur built a profitable business in real estate and furnished their Beverley Hills home with antiques and exquisite ornamental objects. When Rosalinde died in 1995, Arthur donated the entire collection of around 1000 objects to the British nation, and since 2008 it has been on long-term loan from the Gilbert Trust for the Arts to the V&A, where several pieces are on display in the Gilbert galleries (Rooms 71 – 73). You can read more about the Gilberts on our website.

The first part of my responsibilities was research-based. A vast number of objects needed studying and photographing for two new publications. Some also needed cleaning and conserving beforehand. Since many of the objects were carved from stone, or were decorated with colourful hardstones, precise identification of the stones was essential. We invited external specialists Thomas Greenaway and Lola Cindric, who both studied at the prestigious Opificio delle Pietre Dure in Florence, Italy, to help us identify the different stones. They were also able to explain where the stones came from and how they were polished.

We learnt about the art of stone mosaics (also known as ‘commesso di pietre dure’), an ancient Italian mosaic technique in which small pieces of precisely cut semiprecious stones are fitted together, like a jigsaw, to form incredible images which look almost like paintings. The skill needed to create them is mastered only by a few. The art of creating pietre dure panels was at its height in 16th-century Florence, where the state-sponsored Grand Ducal workshops produced them for the elite. They were so popular that numerous palaces and houses were furnished with them across Europe. They are still popular with collectors more recently including in the UK – the singer Freddy Mercury owned a Florentine table with pietre dure stone mosaic, and it’s no wonder that Arthur Gilbert fell in love with them.

Once we’d gathered enough initial information about our objects, curators Alice Minter, Sophie Morris and I embarked on a study trip to Florence. We spent three days visiting churches and palaces where we saw vast number of objects and interiors decorated with marble and stone inlays. We also visited three of the city’s pietre dure workshops, where we were able to speak to the artisans and watch them work. At Scarpelli Mosaici we watched craftsmen carefully transferring the designs from paper to the stone surfaces, then cutting them in an angle using a bow saw moistened with carborundum paste.

Next we toured the conservation labs and galleries at Opificio delle Pietre Dure, where we saw stunning pieces decorated with hardstones and an enormous collection of stone samples covering the walls of several rooms. They also had a wonderful display of historic workbenches and tools.

At I Mosaici du Lastrucci I was able to talk to the craftsmen about a mysterious ‘blooming’ that we’d noticed on one of the tabletops which I was preparing for the loan. There were peculiar white patches on its surface, especially visible on the green verde d’arno leaves. I suspected that humidity or some biological reaction might have caused it. Surprisingly, none of the craftsmen had seen anything like it, but I was told that this limestone was incredibly sensitive to moisture which might explain the reaction. In the end I couldn’t remove the mysterious substance from the surface for risk of damaging the object, but hopefully its cause can be investigated in the future.

When back from Italy, the next phase was to assess and treat all 49 objects and prepare them for travel and display. Since Los Angeles is a seismic region, they all needed mounts that would keep them safe in the event of tremors, but of course the mounts also needed to look elegant and discreet. The heaviest objects required clips and shelves, and these were mainly produced in-house. The smaller objects such as snuffboxes had specialist brass mounts produced by an external mount maker. The objects were weighed, measured and photographed, and detailed condition statements were produced which carefully noted any weaknesses and provided recommendations for handling and display. To ship the objects to the US we were also required to produce CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) statements for any objects that comprised endangered species such as ebony, ivory, pearls, shell, coral, and tortoiseshell.

Once the objects had been packed and crated, we were ready to transport the shipment to the US, and travel to LACMA to oversee their installation. LACMA invited us to observe their team carefully unpacking and installing the objects which we had spent so long preparing. Once all the objects were on their plinths and cases, we were able to take a deep breath and let them complete the installation, set the lighting and finally welcome visitors in to enjoy the show.

Eternal Medium: Seeing the World in Stone is on now at LACMA until 11 February 2024.

Discover more objects from the Gilbert Collection.

I would like to extend my sincerest thanks to all my colleagues at the V&A and at LACMA who supported me during this amazing project. I would also like to thank all the external experts including Ilona Regulski, Curator: Egyptian Written Culture, The British Museum; Ross Thomas, Curator: Department of Greece and Rome, The British Museum; Yannick Chastang, private conservator specialising in veneered furniture and gilt bronzes, and Francis Brodie, Horologist.