What links Dickens with Dalmatians, the Bauhaus with Britain, and a famous four-poster with an infamous chair?

Don’t answer just yet.

Last year we announced our plans for a new Collections & Research Centre in the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park. Preparations are now well under way, and my job is to help make our objects ready for the move. This means I get to work across our different collections and see connections and stories emerge. As was the case with Heal’s.

Originally a bed store, Heal’s have been trading on London’s Tottenham Court Road for over 200 years. Innovators from the start, they took out full-page advertisements in the serialised novels of Charles Dickens, and were early adopters of brand identity. Their distinctive store sign picturing a four-poster bed became such a well-known landmark that Londoners would arrange to ‘meet under the four-poster’.

Ambrose Heal joined the family firm in 1883, as new approaches to design were challenging the revivalist styles of the day. With his maxim, ‘if in doubt, innovate’, Ambrose was grounded in Arts and Crafts ideas but later embraced both French Art Deco influences and the Modernism of Germany’s Bauhaus design school.

Two objects from our Furniture & Woodwork collection illustrate this nicely: a chair made in 1922 as part of the refurbishment of Winston Churchill’s home at Chartwell and an overtly modernist design from 13 years later.

As well as demonstrating a talent for adapting continental styles to British tastes, the Roman Chair has a museum number showing that the V&A acquired it in 1935, the same year it was made. It was clearly recognised as example of good contemporary design.

The 1930s also saw some interesting pieces of bedroom furniture, both for retail – and a notable one-off commission.

The wardrobe was made for Dodie Smith, perhaps best known for writing ‘101 Dalmatians’, who was employed at Heal’s as a toy buyer for ten years. A lively presence in the shop, she had an affair with Ambrose Heal that she delighted in keeping secret from her colleagues. Their relationship seems to have ended amicably, as he subsequently designed a full suite of bedroom furniture for her new London apartment, all of which is now in storage at our Blythe House store.

The Second World War and its immediate aftermath presented understandable challenges to British furniture manufacturers, but also opportunities in the shape of the Utility Scheme –material-saving, Government-approved designs. Facing similar constraints, Heal’s newly formed textile business responded by using small pattern repeats, so as not to waste fabric, and a limited colour palette.

At the Clothworkers Centre in Blythe House we are fortunate to have examples of the vast majority of Heal’s furnishing fabrics – over 1000 pieces spanning four decades. Most of these were given by the Heal family along with their complete business archive, the latter is now stored in our Archive of Art and Design.

Over the last few months I’ve had the chance to examine all of these textiles as part of an audit and research exercise. This brought to light enough stories for a future post, not least Heal’s support for female professional designers and the ever-changing tastes in home furnishings.

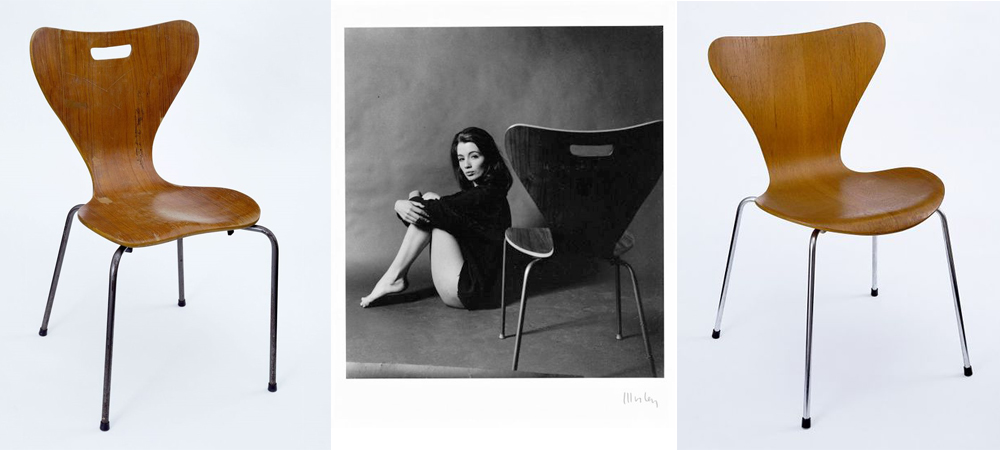

Finally, no account of Heal’s would be complete without mentioning a peripheral, and disputed, connection to 1962’s Profumo sex scandal. Lewis Morley’s iconic portrait of protagonist Christine Keeler shows her sitting on an equally iconic 3107 chair designed by Arne Jacobsen. Except it’s actually an early imitation. Morley was later to claim that it was bought ‘at a Heal’s sale … for fifty bob’, but this is doubtful as we understand that Heal’s only sold the genuine article made by Fritz Hansen – as they still do today.