A Research Fellowship in Lockdown

In October 2019 I began a Research Fellowship in partnership with the University of Brighton and the V&A Research Institute (VARI). My proposal for the fellowship outlined a practice-led research project entitled ‘Looking for the Matriarchive’. This project aimed to investigate and re-frame the female narratives of domestic photographic materials such as family albums, uncovering the often marginalised memories and experiences of women in the home.

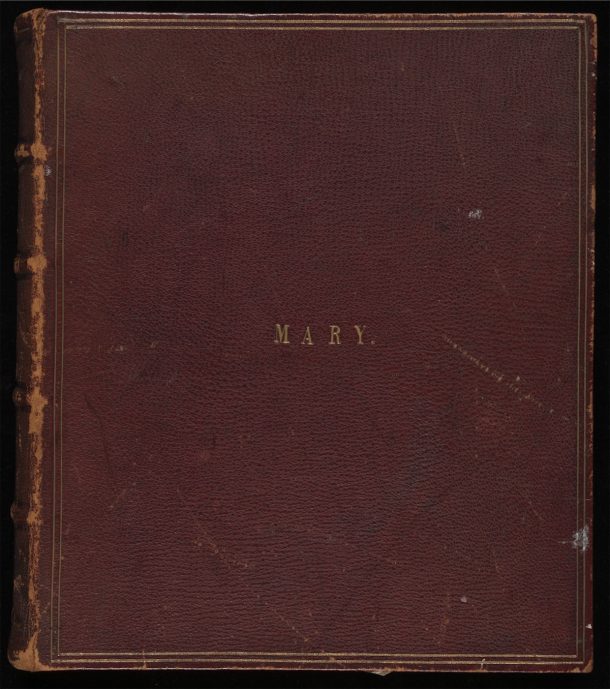

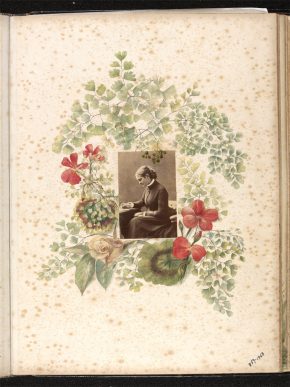

With the support and guidance of Word and Image curators Ella Ravilious and Dan Cox, I began my archival research exploring materials from the Royal Photographic Society (RPS) collection, specifically Victorian photograph albums made by women. The uncatalogued Burnip Album immediately caught my eye, with its leather binding and the name ‘Mary’ embossed in gold on its front cover. On exploring it pages I fell in love with its beautifully hand-painted adornments, photographic collages, and carte de visite portraits.

The carte de visite was patented in Paris in 1854 by portrait photographer André Adolphe Eugène Disdéri as 6.3 x 11.4 cm cards with an albumen photographic print mounted on the front. Their small size, relative affordability and the ease with which they could be produced, sold, and shared meant they became very popular in England during the 1860s; they were also perfect for collecting and displaying in albums. Cartes de visites were almost exclusively portraits of people, usually formally posed full-length photographs taken in a professional studio against a plain backdrop or staged scene. There are many examples of cartes de visites in the V&A collections.

Exploring the Burnip Album

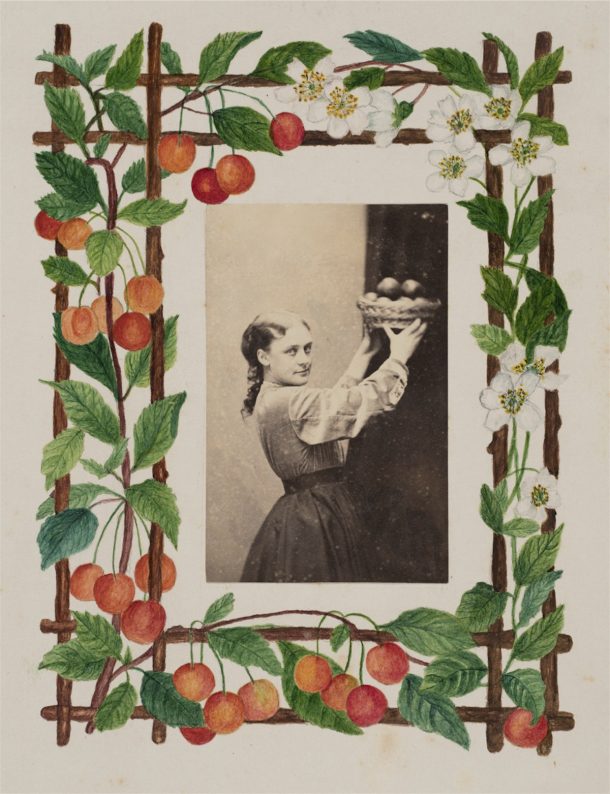

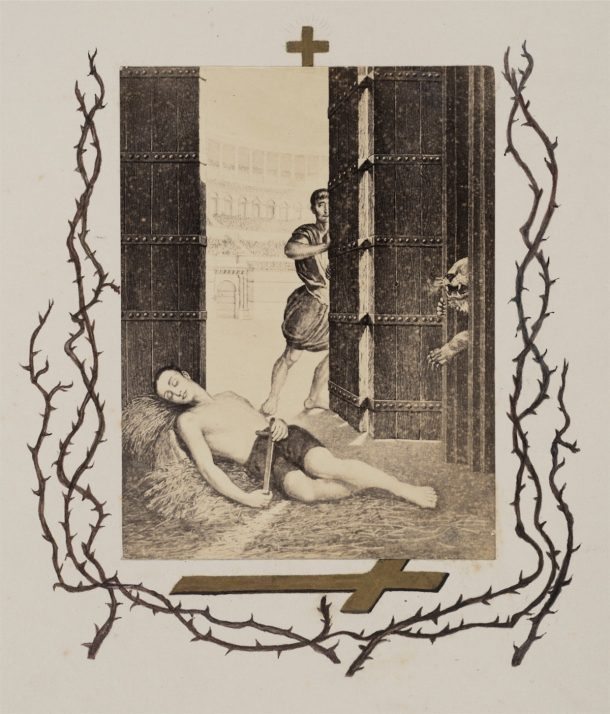

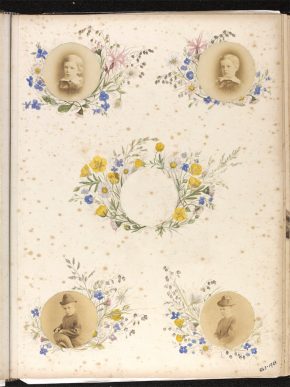

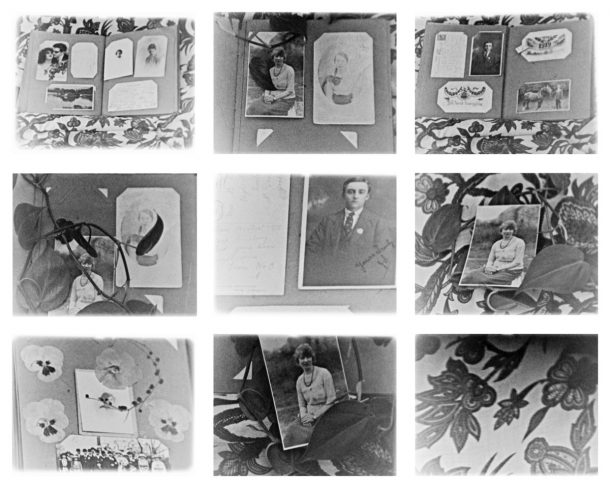

The Burnip Album dates from about the 1860s, and its pages contain a mixture of family photographs, carte de visite portraits and commercially available photographic reproductions of popular paintings. The printed material has been cut out and pasted into the album before being collaged with hand-painted scenes and decorations. Much of the album’s content reflects a traditionally Victorian and feminine style similar to other albums of the same date. Delicate floral borders sit alongside religious imagery and reproductions of paintings that depict morality stories and allegories. Examples of such can be found in the Burnip Album, including the image of a nun holding a crucifix as she stands behind the bars of her convent with a hand painted floral decoration surrounding her. Or the image of what I assume is a Christian man held prisoner in a Roman amphitheatre, the tiger in the edge of the frame perhaps indicative of his fate, the entwining thorns and golden crosses added as a decorative border by our album maker.

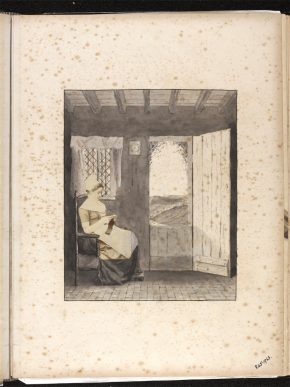

Kate Gough’s photographic album, dated about 1870, also in the V&A’s collection, incorporates a similar style of decoration, indicative of the traditions of album making from this period. In both albums, botanical embellishments and genteel domestic scenes have been painted around photographs to create mixed media collages, which provide insights into the moral ideals of the Victorian era.

Previous

Next

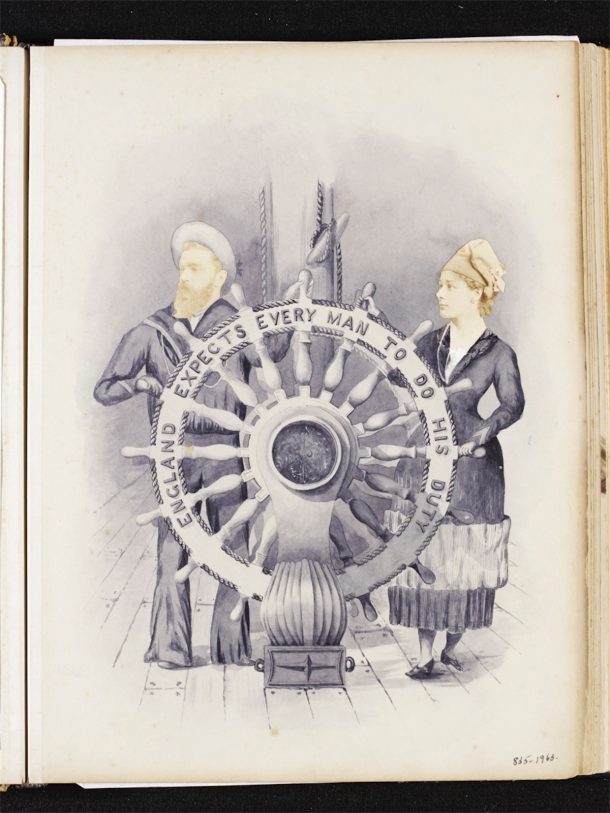

Akin to the Burnip Album, Gough’s album has delicate floral borders and hand-painted scenes encompassing portraits of women partaking in domestic activities such as knitting, reading or writing. There are also images in Gough’s album that pay homage to ideals of duty and honour, similar to the moral themes evident in the Burnip Album. For example, the part painted, part photographic collage of a naval scene depicting a man and woman on the helm of a ship, standing either side of the ships’ wheel – which bears the caption “England expects every man to do his duty”.

Victorian expectations of gender roles are reflected by each album’s content, with women primarily represented in the home and connected to domestic roles. However, some of the scenes created in these albums really surprised me with their creativity and lightheartedness, complicating the stereotype of a formal and oppressive Victorian femininity. As observed by Patrizia Di Bello in her fascinating book Women’s Albums and Photography in Victorian England: Ladies, Mothers and Flirts (page 2, first published by Ashgate in 2007) the domestic or family photograph albums complied during the late 1800s were influenced by an evolving feminine visual culture seen in novels, advertisements, advice manuals, and women’s magazines of the time such as the Lady’s Newspaper (1847 – 1863):

Women’s albums were an important aspect of the visual culture of the time, crucial sites in the elaboration and codification of the meaning of photography…

Bolstered by the commercial availability of photographic portraits in the form of carte de visites which could be collected, shared and curated into albums, a new photographic language emerged, one that spoke not only about women, but to women. The representation of women in commercially available publications and photographs may have been restricted by the social norms of the time, but within personal albums women could create new meanings in their usage of photographic images and mixed media collage.

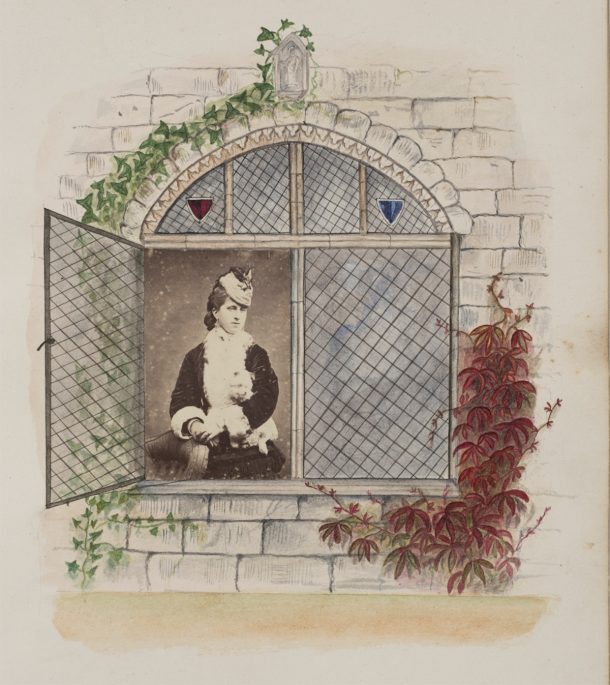

This page from the Burnip album displays a photograph of a well-dressed woman holding a small dog under her arm. The photograph has been placed in the middle of a painted scene of an open window set within a stone wall that has ivy creeping handsomely around it. The ‘real’ photographed woman appears to look out of the ‘imaginary’ painted window, the boundary of painted and photographed becomes blurred and allows a new narrative to unfold. A narrative outside of the usual constrictions imposed by portrait photography, one that is fun and unrestricted.

Other pages in this album also use collage to create imaginative or fantasy-driven narratives. For example, the small child whose photograph has been cut out and pasted on to a painting of lily pads floating on a pond. I became fascinated by the imaginative construction and playfulness of these images. They are interesting not only because they raise questions about the social and cultural roles of photography and femininity during the Victorian period, but because they subvert the traditions of portrait photography.

It is this subversion that allows new meanings to emerge, and that I believe allowed female album makers to create their own identities and tell their own stories. Perhaps the Victorian family album was not only a social tool to display the ideals of womanhood, family values and morality, but also a place for creative expression of private daydreams and subversive humour.

All paths lead home

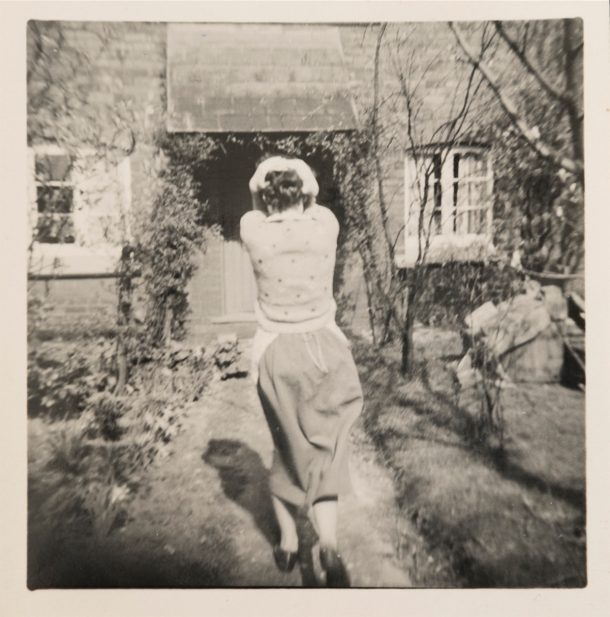

The Covid-19 pandemic and ensuing lockdown changed the way we experience ‘Home’. Domestic spaces immediately became hybrids of home, work, school, gym, creative space, social space and family space. For me, the lockdown meant separation, not only from family and friends, but also from the V&A archival collections I had been working with. Navigating ways to keep my research project moving forward led me to exploring my own family photographs as an alternative.

My work with the Burnip Album ignited a desire to go back to my own family photographs and search for the untold narratives of the women from my past. I began this process by documenting material from my family collections, re-imagining and re-examining the items I keep in my home. Photographs, letters, scarves, pressed flowers, and brooches were all placed before my camera as I slowly photographed each of them against a plain black background. I began to share this new work via blog posts, which also enabled me to stay engaged with my research participants.

As I began posting on my research blog, and exploring these new ideas, I realised the project had evolved in a way I never thought it might – remotely. I didn’t think that sharing the images and stories from my own family collections could work without the human interaction that I had intended for the planned (and currently postponed) research workshops. Yet this digital content seemed to hold a power and level of intimacy I wasn’t expecting.

Interestingly, over the past few months as I have worked within my own domestic space and with my own family photographs, I have begun to see a parallel with the Victorian albums and women that I’ve been researching. Women stuck at home with their photographs sometimes have to get a bit creative, it seems.

This new way of working led me to me producing an entirely new body of work, a moving image piece titled ‘The Unfixed’, that featured my own family photographs and albums. This work was showcased at the recent Brighton Photo Fringe 2020 festival as a collaborative exhibition I undertook with artist Kirsty Thomas as the artist duo ‘Remember what binds you’. The exhibition ran from the 1 – 11 October 2020 at Gallery 40 in Brighton, under carefully considered Covid-19 safety measures. We had virtual and physical visitors, gave artist talks and tours in-venue and online, and even arranged some (very exclusive) socially distanced Private View events.

The Unfixed is an eight minute long, black and white, silent film piece originally filmed on 16mm. It was presented in the gallery space as an installation which also included photographs and objects from my own family collections. The work is an unsettling exploration of a family photograph album and a seaside landscape, all made during the lockdown summer of 2020.

‘The Unfixed’ would not have been made without the unique opportunity offered by the V&A/Brighton Exchange Fellowship, combined with the unusual circumstances of lockdown, interrupting and pausing my research work, thus allowing it to develop and flourish in a new way. I am still desperate to get back to the V&A archives when I can, yet I’m pleased this project has managed to evolve and take on a new direction within the restrictions of lockdown.

For more information about my research and photographic practice, please see the project blog, and exhibition website.

The 19c albums are of interest but need, I think, more historical contextualising. For example, religious and political issues surely are relevant, given two of the pictures in the Burnip album and the call to duty naval picture in the Gough one. Cross-referencing with contemporary family magazines such as Cassells and Fun might be interesting.