In Spain, there are efforts afoot to discover the exact location of the grave of one of the country’s greatest writers, Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra. Despite the instant popularity of his masterpiece ‘Don Quixote’, he died in poverty and was buried somewhere in the Convent of Trinitarians in Madrid, but the exact location is unknown.

Inspired by this, I decided to go on a Cervantes hunt myself to see what copies of this famous work we have in the NAL; I was surprised to find more than 50 from a variety of places and times, almost all with illustrations of the eccentric Don and his adventures. One of the most illustrated works of all time (by artists as wide-ranging as Hogarth, Goya, Crane, Rackham, Dali and Picasso), the depictions of Don Quixote are also interpretations of the text, illuminating how the story has been read and interpreted variously over the years . Here follows a very small selection.

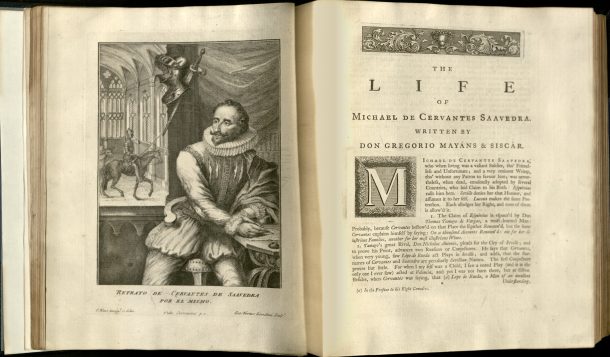

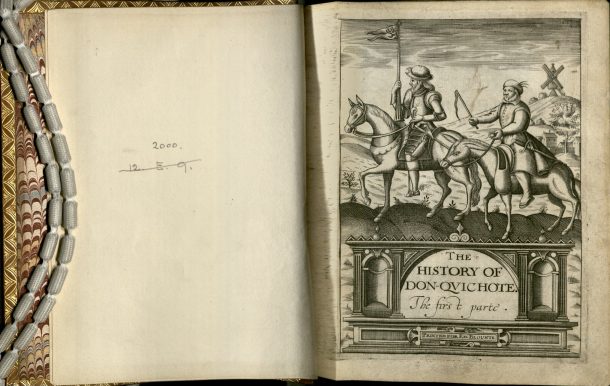

Don Quixote was first published to some acclaim in 1605. It is the captivating story of an aging gentleman too fond of books on chivalry, who fancies himself a glorious knight and embarks on a series of misguided quests that include mistaking inns for castles, empty wine sacks for knights and windmills for giants. The earliest copy in the NAL is an English version from 1620. The frontispiece woodcut shows the already iconic windmill in the distance, while Quixote wears the barber’s bowl he believes is the legendary helmet of Mambrino which makes the wearer invincible. The image is slightly rustic and represents early readings of the work as a popular and carnivalesque collection of stories.

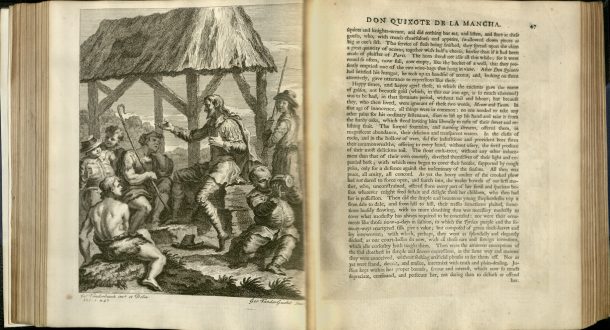

Don Quixote was reimagined in the 18th century, as seen in the lavish deluxe publication funded by Lord Carteret as a gift for the scholarly Queen Caroline in 1738. Richly presented with illustrations by Vanderbank, the story of Don Quixote was aimed at an elite and learned audience interested in classical learning and moral tales. This image of the Don from the NAL’s 1742 copy shows him regaling a group of goatherds with tales of a chivalric golden age. As was the fashion in the 18th century, it is a vision of a sentimental, rather than absurd or unhinged, man.

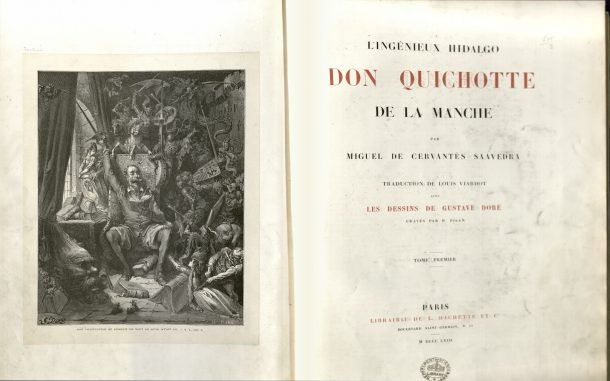

Perhaps the most famous illustrator of Don Quixote was Gustave Dore, whose dark, fantastic 1863 edition of Don Quixote shows the Don as a romantic dreamer. His version became the definitive image of the Don.

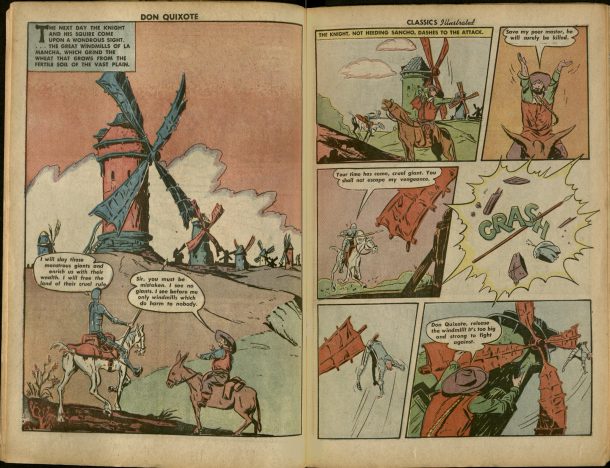

With the explosion of children’s literature in the late 19th and early 20th century, Don Quixote was rewritten as a classic for children, regaining some of its comic and burlesque aspects as slapstick was favoured over satire or sentiment. The NAL’s Renier collection of children’s books has over 20 versions of the story such as this from the Classics Illustrated comic book series, drawn by Louis Zanksy in 1944.

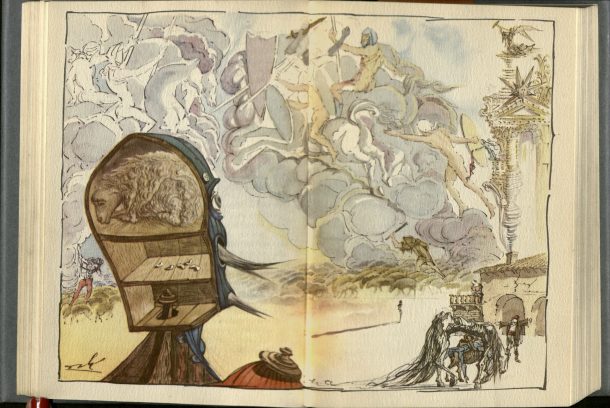

The psychological aspects of Don Quixote are emphasised in this version by Dali, where the Don inhabits a surreal dream-world and we can literally see inside his head as he sees a herd of sheep as army. In the 20th century, critical theories about the Don’s behaviour have included diagnoses of schizophrenia and dementia.

Whilst the final resting place of the body of Cervantes may never be found, he lives on through his ever-popular and seminal work, and on the shelves of the National Art Library. The book can be tragic and comic, funny and thought-provoking, a romp or a satire; it explores reality, deception and madness, as well as recounting the exploits of a wide range of memorable characters. As we have seen in some of the illustrations accompanying this absorbing and puzzling story, it can be read in many ways and has been reinterpreted by each generation. Many have looked inside Cervantes story and found themselves

Hello, thank you for your scans. Is it possible to scan the actual book page where it is written: “Let the dogs bark it is a sign that we are moving forward”?

We’ll thank you for that; I promise it wont be used for commercial purposes.

Thanks in advance,

Moises from Guatemala

Hello Moises from Guatemala,

Thank you for your interest in my blog. If you want a scan of a work in the library please request one using the following link:

http://vam.altarama.com/reft100.aspx?pmi=05ccbankKE

You can find more information about the library’s services here:

https://www.vam.ac.uk/info/national-art-library/

All the best,

Ruth Hibbard