Harry Dougall recently graduated with an MA in Curating the Art Museum from the Courtauld Institute of Art. His dissertation Alexander Barker (1797-1873) and the South Kensington Museum: Private Serving Public in the Victorian Art World offers the first attempt to understand and situate the collector Alexander Barker within the context of the mid-Victorian art-world. In this guest blog, Harry highlights Barker’s activity as a significant lender, seller, adviser and donor to the South Kensington Museum and explores his disrupted legacy.

I came across the name Alexander Barker primarily in relation to the significant purchases made by the National Gallery at his first posthumous sale which took place at Christie’s in 1874. Among the thirteen pieces acquired many still rank among the best-loved works in the National Gallery, including Piero della Francesca’s The Nativity (1470-5) and Sandro Botticelli’s Venus and Mars (1485). However, the latter only represents one element of Barker’s activity, ignoring his involvement with decorative arts and his relationship with the South Kensington Museum. Thus, his influential role in the mid-Victorian art world had yet to be fully explored.

Whatever I have is the best, were I to have a jackass, it would be the best jackass in England.

This declaration by Barker highlights his genuine belief in his own taste and judgement for works of art. This belief is attested to by many of Barker’s contemporaries, activities, and acquisitions. His network was vast incorporating continental dealers, aristocratic collectors and leading museum officials. Equally his activities fluidly blurred boundaries, not only between collector and dealer, but also private and public. He came from humble beginnings starting out as an apprentice bootmaker in his father’s shop; but by 1850 he had established a reputation as a leading collector residing at the grand residence of 103 Piccadilly, and by his death in 1873 his estate was valued at a vast £160,000.

Records in the V&A Archive provide an insight into Barker’s relationship with the Museum and its leading officials such as Henry Cole, J.C. Robinson and Richard Redgrave. While Barker was never employed by the Museum to the degree of some of his contemporaries (e.g. John Webb and C.D.E Fortnum), he was actively involved in developing the Museum’s collections through lending, selling, and advising. Barker was not unique in this capacity; the Museum had an intimate and mutually influential relationship with a community of collectors that helped not only sustain but develop the collections. However, Barker was at the heart of this community; alongside J.C. Robinson he was an original member of the Fine Arts Club (1857) and founding member of the Burlington Fine Arts Club (1868), he regularly contributed objects for discussion and hosted/attended meetings. With decorative arts knowledge still in its infancy, the latter society was fundamental in shaping the parameters of taste, allowing an exchange of information and expertise that subsequently benefited both private individuals and the Museum.

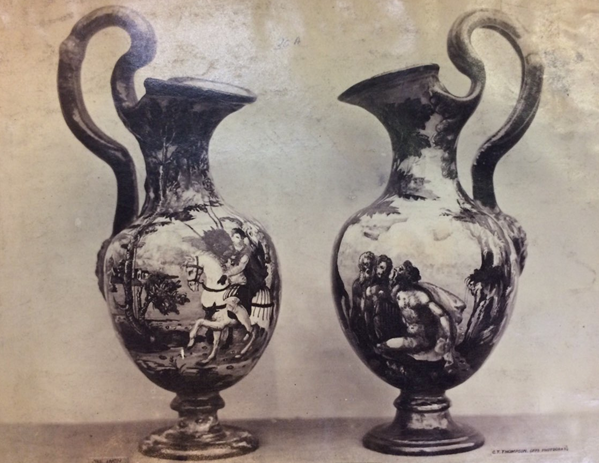

Barker was a regular member of exhibition advisory committees, a role offered by invitation to ‘noblemen and gentlemen eminent for their knowledge of art’. At the South Kensington Museum, he was on committees for numerous loan exhibitions including the series of National portrait exhibitions (1866, 67 and 68), Portrait Miniatures (1865) and the Special Loan Exhibition held in 1862. Lending to these exhibitions allowed collectors to develop public taste and fulfilled their public role; indeed, to the latter exhibition Barker lent a total of 55 objects including a Louis XVI cabinet, ivory carving, Venetian glass, Crystal work, and 32 pieces of majolica. Furthermore, in 1862 he was sent by the Museum to select works for the said exhibition from collections known to him in Paris and conducted this task at his own expense.

This crucial public role played by private individuals in relation to temporary exhibitions also extended to the development of museum collections. While loaning to exhibitions was common-practice, the use of collectors’ loans within a permanent collection was pioneered by the South Kensington Museum. Independent from his loans to exhibitions, Barker lent around 500 objects to the Museum between 1859 and 1867 a number of which remained until his death in 1873. While most collectors’ loans generally lasted two or three years, Barker’s lasted anywhere from one to seven years at a time, as Cole’s diary entry for 26 June 1857 states:

Mr Barker said we might keep his ivories as long as we liked.

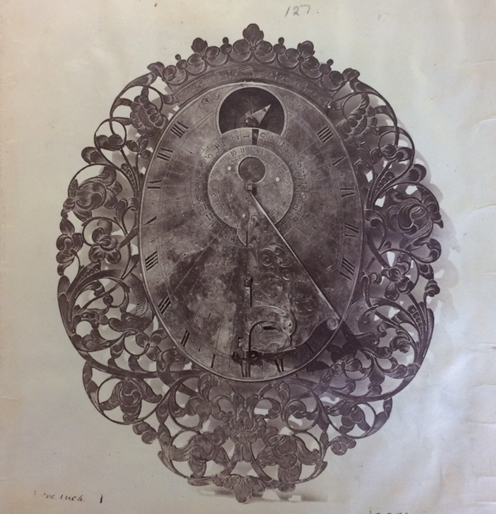

In 1859 alone Barker lent 257 specimens to the Museum, including majolica, bronzes, crystal, glass, triptychs, daggers, and carved ivories. While the material lent generally followed the areas of interest in the applied arts formulated by the Museum, it was also diverse. Barker’s loans included objects such as a Large Coconut mounted, Sundial with compass, Bucket with serving handle, and Russian wooden crosses.

Loans were an effective way for private individuals to fulfil their public role, but museum acquisitions from collectors also contributed to the development of collections. Overall the South Kensington Museum acquired 20 objects from Barker (excluding his bequest); 14 pieces of French porcelain (Sèvres and Niderviller), 3 panels of Flemish sixteenth-century stained-glass, two Plaster Casts from biscuit, and a French eighteenth-century writing table by the celebrated David de Lunéville.

However, given the amount of loans accepted by the Museum from Barker the number of acquisitions made were comparably small. An explanation for this can be found in a pre-sale report by one of the Museum’s Art Referees Matthew Digby Wyatt in which he states:

To buy out of this collection is not to buy at the break up of any historical series of accredited and well authenticated art-treasures but to set the wits of those comparatively unacquainted with the dodges of the current trade, against those of one who passed much of his life in studying how most skilfully to so combine old and new as to hide the latter as far as possible.

While Wyatt raises an important issue, the activity of ‘improving’ objects was common practice among both dealers and collectors throughout the nineteenth-century, and the question of genuineness was viewed very differently from today.

This reputation of nineteenth century dealers/collectors for vamping up their objects arguably influenced the questionable decision of Ralph Edwards (V&A Keeper of Woodwork and Furniture, 1937-54) to dispose of Barker’s museum bequest of eighteenth-century Venetian furniture in 1952. Out of Barker’s vast collection 1,811 objects were sold posthumously at auction, but he chose one specific set of furniture to bequeath to a public institution, which included six Venetian chairs, a sofa/state-bed, a pair of corner-cupboards, and six curtains with their valances of Genoa velvet. In 1875, the Art Journal reacted to the display of the bequest in the Museum stating:

As illustrations of the high-class furniture and decoration of a period more noted for a love of display than of elegance, this gift is a notable one.

The positive reception of the bequest is affirmed by the fact it remained on display from 1875 until at least 1920. In the disposal files relating to the bequest Edwards and his colleagues on the Board of Survey recommend selling on the basis that all items were ‘Bad 19th century Reproductions’. Validation that the set was arguably not ‘Bad 19th century reproductions’ came as recently as the 1990s, when curator Clive Wainwright stated that ‘Barker left some splendid Venetian furniture to the Museum’.

Indeed, Barker’s chairs are exactly similar in design to a pair currently in the Wallace Collection bought by Redfern for the fourth Marquess of Hertford at the Stowe sale (1848). The chairs also match a pair displayed in a 1983 exhibition at Colnaghi. In both the Wallace and Colnaghi catalogues the chairs are considered to have been part of a suite of furniture created for the Doge of Venice, Paolo Renier (1710-89). According to Henry Rumsey Forster’s Stowe Sale catalogue, this suite of furniture and ‘other superb specimens from the Doge’s Palace at Venice’ were brought to London in 1834 by the Italian dealer Gasparoni. Barker’s bequest of a Venetian boudoir was symbolic, constituting the only objects he bequeathed to any public institution. It is an area of decorative arts which the V&A are currently lacking and had these remained his legacy would arguably be more pronounced.

I’m conducting research on Alexander Barker and would love to be in touch with Harry Dougall. Would the V&A have contact for for him?