Halloween as we know it today came to us from Irish and North American traditions. Besides from making turnip and pumpkin lanterns, dressing up in scary costumes and trick-or-treating, one of the popular festive activities previously associated with Halloween in Ireland was divination rituals and fortune-telling practices carried out as part of the celebration. These practices were associated with the Gaelic Samhain (summer end) festival which marked the end of the harvest season and beginning of winter or ‘darker half’ of the year.

An important aspect of Samhain is the temporary connection it opens to the ‘other world’. This has always made it a time to communicate with the deceased. Because of the transient quality of this period, it was also considered an excellent time for divination. In Halloween, fortune-telling methods were used by means of traditional Samhain symbols such as apples and nuts, in order to tell the future and seek answers of the unknown. During the 20th century these divination methods became party games which were often related to questions around marriage and love.

Divinatory practices were also extremely popular in the Middle East. However, these practices were carried out all through the year and the practitioner was often guided by astrology in order to find the most suitable time for his practice.

My display in the Jameel Gallery of Islamic Art which opened in June includes a selected number of objects that associate with amulets, talismans and fortune-telling in the Middle East. Among the objects on show there is an astrological plaque with a set of dice. I thought today would be ideal to introduce this object since it relates so perfectly to the theme of the day.

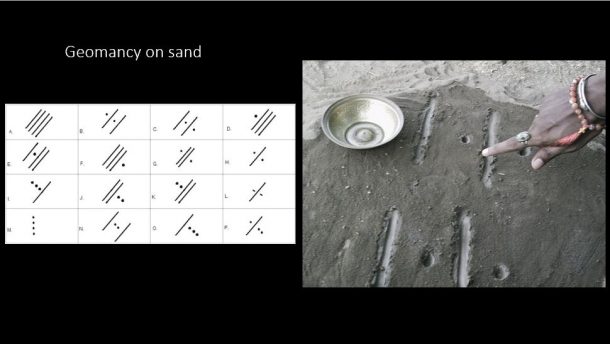

Of all divinatory practices used in Islamic cultures, it seems that only astrology was more popular than what is known in Arabic as ‘ilm al-raml (‘the science of the sand’), which came to be known as geomancy in medieval Europe. The origin of the distinctly Islamic art of geomancy is uncertain, but it appears to have been well established in North Africa, Egypt and Syria by the 12th century. Unlike astrology, geomancy did not require astronomical observations and calculations. Instead, divination was accomplished by forming and then interpreting a design, called a geomantic tableau, consisting of 16 positions, each occupied by a geomantic ‘figure’.

The figures occupying the first four positions were determined by marking 16 horizontal rows of dots on a piece of paper or a dust board (takht), a tablet covered with fine sand on which numerical or other calculations could be made and then easily erased. Geomancy had its own distinctive literature, with numerous manuals. The practice tended to give answers to more specific questions than astrology. Popular questions were ones relating to the outcome of an illness, outcomes of pregnancy, and finding love and fortune. This method can also tell you about unseen events such as the fate of distant relatives, the location of lost or buried objects or a person’s unspoken thoughts.

Fortune-tellers and the use of ‘ilm al-raml are a common feature amongst illustrated manuscripts and stories from around the Middle East. One of the stories in The Thousand and One Nights, for example, describes Prince Qamar al-Zaman, pretending to be a fortune-teller to gain access to princess Budur in the king’s palace. Qamar carries as tools of his trade ‘a set of instruments, as well as a [geomantic] divination tablet and an astrolabe of gold’. He calls out, ‘I am the scribe, the calculator, the astrologer. I am he who calculates, who knows what is hidden, who divines the answers, and who writes charms. Where is the Seeker?’

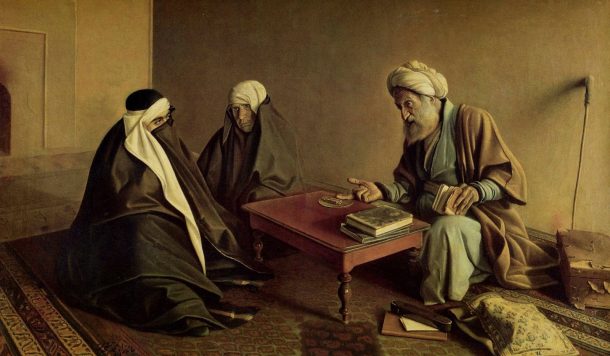

In Iran the term raml is applied to two types of divination. One type is the traditional form of geomancy described above. The other, frequently described by European travellers, involved the throwing of brass dice strung together in groups of four. Only four sides of each die are numbered, while the other two sides are pierced to allow the spindle to pass through. Although these are commonly called ‘geomantic dice’, their markings do not produce a geomantic figure. Divination using such dice is a form of lot-casting known as fa’l in Persian, rather than true geomancy.

The plaque on display in the Jameel gallery and the accompanying sets of dice were made to predict the future as discussed above. A diviner would throw the dice, and then interpret the results with the aid of the astrological designs on the plaque as seen in the painting by Kamal al-Mulk. The engraved designs include the signs of the zodiac, along with various Quranic inscriptions.

Fascinating post and topic. Where can I see this object?

Thanks for this blog, it was so intresting!

Thank you, Mary. This object is on display in the Jameel Gallery of Islamic Art in the V&A (gallery 42).