Franca Falletti is the Former Director of Galleria dell’Accademia in Florence

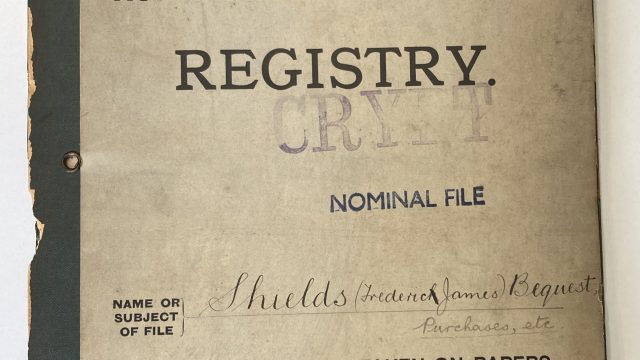

The Granduke of Tuscany commissioned from Clemente Papi a plaster mould and a copy of the sculpture of the David by Michelangelo, on 29 August 1846.[1] Soon afterwards, Papi also made a wax mould in preparation for a bronze copy of the statue, because he foresaw that other copies might be requested in the future.[2] Indeed two plaster copies were ordered immediately. One was donated to the British Government (displayed at the V&A) and the other was used to test options to relocate the original statue of David, since safekeeping concerns had already arose.[3] Papi’s work proved incredibly important, because from then on all the copies (total or partial) of Michelangelo’s David have been made from his plaster mould, which has remained in Florence, at the Gipsoteca of the Istituto Statale d’Arte (fig. 1). This has prevented the original statue from being damaged further due to the making of additional moulds.

Even the making of Clemente Papi’s mould from this Michelangelo masterpiece was not entirely without damaging consequences. We saw proof of this during the conservation work carried out at the Galleria dell’Accademia between 2002 and 2004.

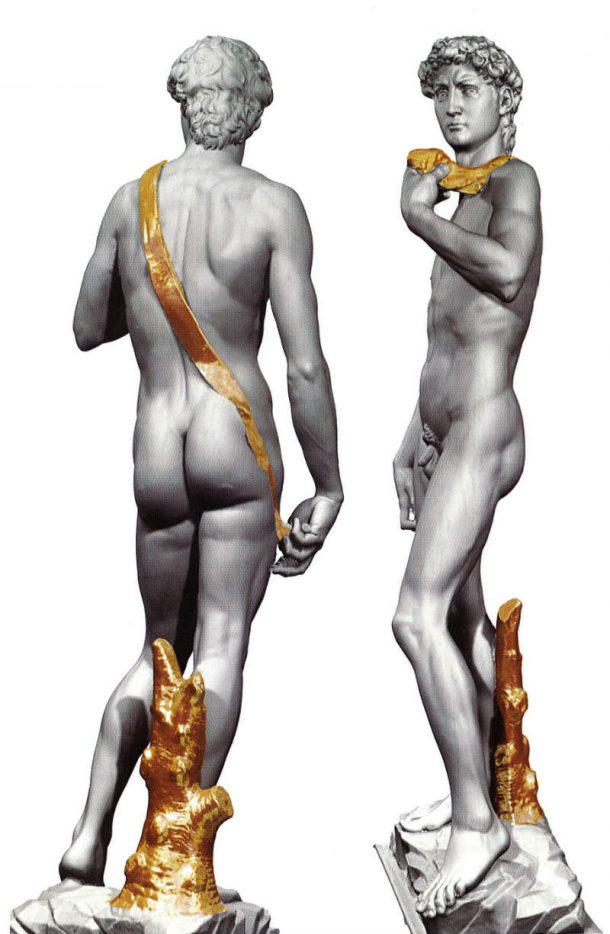

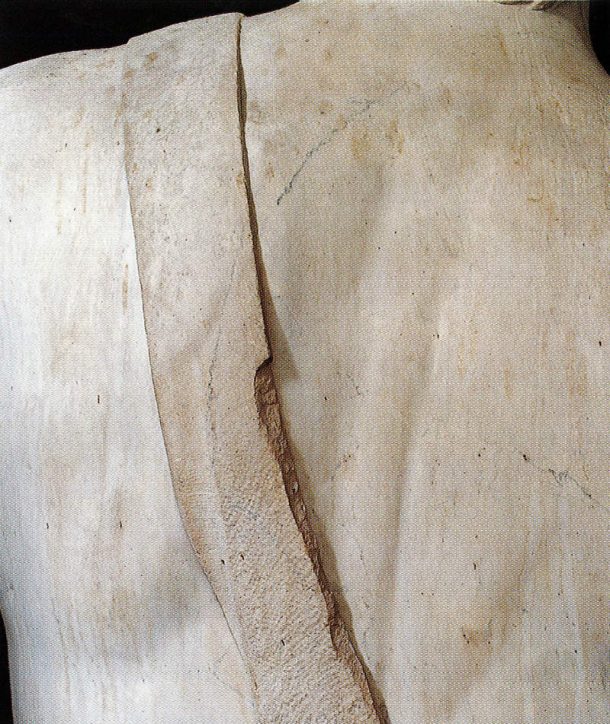

While observing the surface of the sculpture before the conservation works began, visible plaster residues were identified in a few hard to clean spots, for example between David’s toes. Such residues had almost certainly been left from the making of the plaster mould. Other plaster residues were also found on the sling and on the tree trunk. These, however, could be traces of the preparation for an old partial gilding, applied to ‘[…] the sling, the tree trunk and the wreath […]’, (fig. 2), the latter being ‘a thread of brass with twenty-eight copper leaves’.[4] As it is only through payment documents that we know of the existence of a crown wreath, we can assume that a crown had been made. However, we don’t know if this was placed on David’s head, nor for how long it has remained there. No damage resulting from oxidation was found on the head of the statue. This may suggest that the crown might have been there for only a short period of time. The sling and the tree trunk, however, were gilded by Michelangelo. Their surfaces appear rough, as this would have helped the gold adhere to the sculpture. Along the sling a microscopic fragment of tin has been found, which can also be traced back to a gilding. Because this fragment (fig. 3) has been found along a chipped edge, however, it does not refer to the originalgilding. It might be linked to restoration works commissioned by Granduke Cosimo I, in 1543,[5] following damages inflicted to the statue (specifically to David’s arm and left hand) during uprisings that took place in Piazza della Signoria on 26 April 1527, edscribed at length by chronicler Jacopo Nardi.[6]

Abundant residues of beeswax were also found. At times, these can be easily recognised, as the beeswax has condensed into tiny brown-orange droplets. More often, the beeswax constitutes an almost colourless thin layer that seems to cover the majority of the statue’s surface. This thin layer could have a number of origins. On 8 June 1504, the statue of David was carried to the piazza and placed on top the arringario (fenced platform) outside Palazzo Vecchio. Once there, the statue was finished by Michelangelo inside a wooden shed that no one else could access. The David was unveiled only on the following 8 September.[7] There are no records on the technique or the materials used by Michelangelo for the finishing of the sculpture, but it is likely that some protective finishing substance was used. Unfortunately, due to the weathering and the harsh cleaning procedures performed on the statue during the 1800s, it is unlikely that residues of protective substance used originally by Michelangelo could now be identified with certainty. There are also many years in the life of this statue that have gone undocumented. It’s possible, therefore, that the surface beeswax mentioned above could have been applied during that time. Yet we cannot exclude that this might be a residue left from the making of the mould by Clemente Papi. That mould would have necessarily been made with the help of releasing agents, but we do not know their composition. We only know that Clemente Papi was chosen for the commission because ‘[…]he had become famous, especially because of methods he had invented so as not to harm original works, which had until then often been damaged by the poor practice of greasing them with pork fat and with olive oil […]’.[8] Excluding olive oil and pork fat, there are many other materials that Clemente Papi could have used, including beeswax.

The analysis and tests carried out in preparation for the recent conservation campaign also revealed the presence of a few pencil marks, which might indicate some kind of technical information. Perhaps they could indicate cutting points of plaster piece-moulds, and, therefore, might have been drawn by Clemente Papi. As an alternative, they might date to 1873, when the statue was moved inside the museum. In this case they could indicate the grip points of the ropes used to lift the David. Similarly, we think that the deep incision (two straight parallel lines that cross a third line, perpendicular to the other two) visible on the horizontal surface of the base could be interpreted as a technical reference as well.

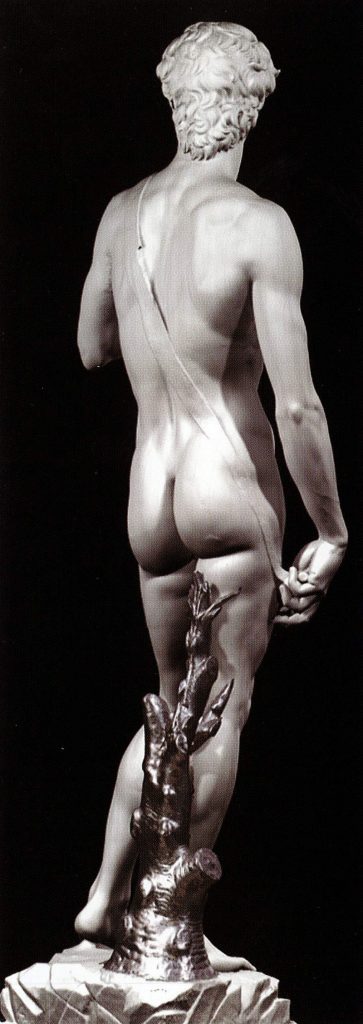

Nevertheless, the most severe damages produced by the making of the mould in the 19th century affected the very structure of the sculpture. David’s ankles and the tree trunk against which his right leg leans show numerous horizontal cracks (fig. 4). These cracks were a major concern throughout the 19th century and they were one of the main reasons why it was decided that the statue should be moved into a more protected location. To this day, the fragility of David’s ankles remains a serious issue, which was tackled but not entirely resolved during the last conservation campaign carried out on the sculpture. Many causes for this particular problem can be identified. The oldest of these was detailed by Jacopo Nardi. He wrote that, when Pier Soderini was exiled from Florence (31 August 1512), there were many signs of disdain from the Heavens. Among these, ‘lightning struck the Palazzo della Signoria[…] the same lightning (or maybe a different one) shifted the marble base, which supported the marble statue of the David, that was near the fence.’[9] According to the chronicler, this was the first and oldest cause of the damages to the base of the statue and of the cracks on its ankles.

The mould made by Papi was surely another cause of stress to the David. The weight from the enormous plaster piece-moulds challenged the stability of the sculpture. ‘The original mould in the many pieces that compose it (and those were no less than 1500, some of which weighed not less than 680 kilograms) is still extant to date, because of the cares provided by Papi […] in the archives of R. Fonderia’.[10]

A letter, dated 31 December 1847, clearly states that the stability of the David would have been challenged by the making of a plaster mould. This letter was sent by the Director of the Regie Fabbriche, Girolamo Ballati Nerli to the President of the Accademia Cav. Commendatore Antonio Ramirez di Montalvo, asking for an evaluation of Papi’s work. One hundred zecchini were proposed as compensation because of the difficulty of the work which had to be carried out outdoors, and on ‘a nearly unstable and enormous’ statue. We must underline the lightness with which this project, full of uncertainties, was carried out. It seems that the enthusiasm brought on by Papi’s skills in dealing with obvious risks overcame all doubts. In his written response, dated 18 January 1848, the President of the Accademia specified that the mould had been made during the summer, as common sense would have suggested, to facilitate the drying out of the piece-moulds, thus reducing to a minimum the amount of time they remained on the marble statue.[11]

The first official document that details the dangers to which Michelangelo’s masterpiece was exposed, including structural issues, is a letter by Antonio Manetti, Director of the Fabbriche Civili dello Stato, to the then President of the Accademia di Belle Arti, Luca Bourbon del Monte, on 24 October 1851.

As an immediate consequence of this letter, Clemente Papi was tasked with carrying out conservation works to stabilize the statue. Papi’s proposed plan was incredibly complex, and so we feel relieved that it was never put into action. It envisioned to encase the tree trunk behind David’s right leg with a metal branching (tinned copper), which would have extended up to the thigh so as to support it firmly (fig. 5). To give further stability, in case the original marble of the thigh seemed too fragile, the plan also proposed new marble should be added in.

Because of increasing concerns, on 3 January 1852, the Accademia di Belle Arti formed a first committee to study the conditions of the David. The resulting report contains an incredibly detailed description of the cracks on the ankles, along with sensible structural considerations.[12]

Fourteen years later, in 1866, a second committee was established, with a subcommittee charged with performing a technical examination of the statue of David.[13] The president of the subcommittee was Emilio Santarelli, who having been part of the first committee back in 1852, was best equipped to evaluate the progression of the damages to the David. The final report describes in minute details the cracks in the statue, some of which we learn have extended further since 1852. Another source of deep concern was the projection forward from ‘the gravitational centre of the statue over the feared breakage […]’ which measure 28 centimetres.

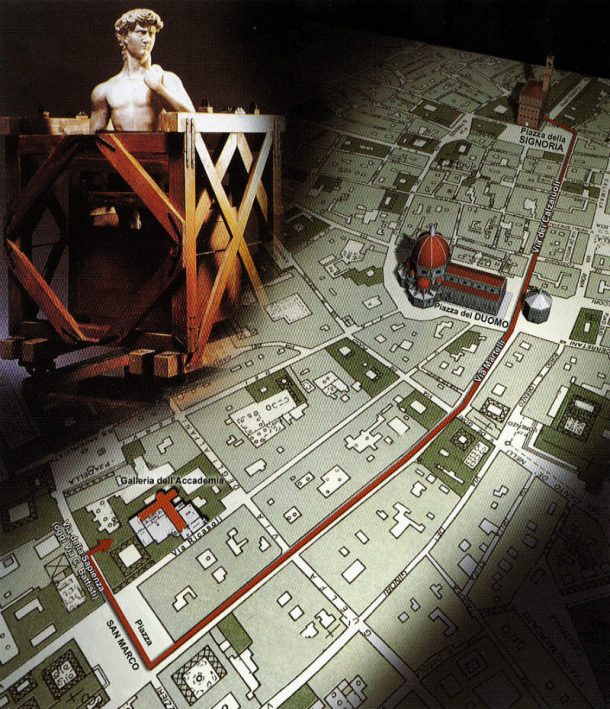

In 1871, Del Sarto, the first Ingegnere dell’Uffizio d’Arte del Municipio of Florence, was tasked with a study on the stability of the David. On 6 January 1872, a new (third) committee was formed, called the Menabrea committee. Following the alarming results of tests and analyses, a first programme of works to consolidate the statue was carried out in situ, in July 1872.[14] Finally, between July and August 1873, the David was moved to the Accademia di Belle Arti (fig. 6).

The Menabrea committee, which remained operational even after the removal of the statue from Piazza della Signoria commented that:

‘Once the debate was open some expressed the opinion that for the reasons discussed for a long time by other committees it would be useful firstly to consolidate the statue as not to give other motives of alarm over its safety. Others believed that the dangers then feared had been greatly diminished by having moved the statue. This is because the damages that had already occurred were related to the statue’s exposure to atmospheric elements, to the frequent transit of heavy carriages in the proximity of the statue, or more precisely to the contact with the pedestal on which it rested on, to the strength of the wind which hit it, and to the frailty of the base and the position of the enormous statue which leaned forward, and therefore they didn’t think consolidating works were necessary’.[15]

We are left to believe that this second opinion prevailed, because no source has reported the use of any supporting beams. People convinced themselves that it would suffice to keep the position of the statue on the new pedestal ‘[…]a little bit behind, without harming (it) in the slight’, (fig. 7).[16]

With regards to archival sources the following acronyms were used: A.A.B.A – Archivio Accademia di Belle Arti; A.S.C.F. – Archivio Storico Comunale Fiorentino.

The document cited in this blog were transcribed and published in AA. VV. Exploring David, diagnostic tests and state of conservation, Franca Falletti, Appendix, pp. 74-95.

Franca Falletti

Franca Falletti was born in Florence, and she continues to live and work in the city.

She obtained a degree in Medieval and Modern Art History from the School of Letters and Philosophy at the University of Florence, in 1974. There she was a student of Roberto Salvini and Ugo Procacci. In 1975 she specialised in the same subject, at the same school. She initially worked as a freelancer, collaborating with scholars and institutions on matters of research, cataloguing and teaching. In June 1980 she was nominated managing officer of the Cultural and Historical Heritage Office of the provinces of Florence, Pistoia and Prato. In December 1981 she became the Vice Director of the Galleria dell’Accademia. She was Director of the Galleria, from March 1992 until 28 February 2013.

As Director of the Galleria dell’Accademia she supervised and/or curated all the exhibitions, displays and restorations at the museum, promoting scientific activities, publishing studies and catalogues. She curated the redevelopment project of the Gipsoteca of Lorenzo Bertolini, as well as the collection of Florentine paintings with gold ground and those of the Museum of musical instruments of the Conservatory of Music Luigi Cherubini.

Moreover, between 2002 and 2004 she directed the restoration project of the statue of David by Michelangelo. She also coordinated the many studies undertaken in that occasion by numerous Italian and European research institutions and universities. She has curated many exhibitions related to the Galleria dell’Accademia, as well as displays and events related to Contemporary Art, such as Forme per il David – Baselitz, Fabro, Morris, Kounellis, Struth in 2004; Robert Mapplethorpe – La perfezione nella forma in 2009, and in 2012, Arte torna arte.

Acknowledgements:

I would like to extend my sincerest thanks to Caterina Tiezzi for the translation of my text, and I would like to thank Silvia Catitti for her generous help in reviewing the translation.

Footnotes:

[1] A.A.B.A. Filza 1846, inserto 85.

[2] This bronze copy is now visible at the centre of Piazzale Michelangelo.

[3] A. Faleni, Notizie storiche del David del Piazzale Michelangelo e cenni biografici del Cav. Prof. Clemente Papi Firenze Tipografia della Gazzetta dei Tribunali, 1875, pp. 32-33.

[4] K. Weil Garris, On pedestals Michelangelo’s David, Bandinelli’s Hercules and Cacus and the sculpture of the Piazza della Signoria, in “Römisches Jahrbuch für Kunstgeschichte”, Band Zwanzig 1983, pp.377-415, p.385; R. Ristori, L’Aretino, il David di Michelangelo e la “modestia fiorentina”, in “Rinascimento”, Firenze, Olschki, seconda serie, volume XXVI, MCMLXXXVI, pp.77-97.

[5] G. Vasari, Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori ed architettori , Firenze, 1568; ed. cons. G. Vasari Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori ed architettori, con nuove annotazioni e commenti di Gaetano Milanesi, Firenze 1906, vol.VII, p.156 nota 2.

[6] J. Nardi, Istorie della città di Firenze, Firenze 1838-1841, vol. II [1838], pp.23-24.

[7] A. Zobi, Del progetto di rimuovere la statua del David celeberrima opera del Buonarroti dal sito in cui sta attualmente, Memorie della Società Colombaria, 30 novembre 1854, Firenze 1854, p.13.

[8] Faleni, 1875, p.22.

[9] Nardi, vol. I [1838], libro V, pag.456.

[10] Faleni, 1875, p. 33.

[11] A.A.B.A. Filza 1848, inserto 6.

[12] A.A.B.A. Filza 1852 n.41A, inserto 98.

[13] A. Gotti, Vita di Michelangelo Buonarroti narrata con l’aiuto di nuovi documentiFirenze, 12 settembre 1875, vol. II, pp.40-48.

[14] A.S.C. F. Filza speciale 5324, Inserto 3, lettera del Sindaco al Menabrea datata 2/3/72.

[15] A.S.C.F., Filza speciale 5324, inserto 5, in data 4/7/1874.

[16] A.S.C.F., Filza speciale 5324, inserto 6, in data 5/7/1874.

Thank you very much for the information I get many references to my educational articles on campus

You have provided an nice article, Thank you very much for this one. And i hope this will be useful for many people.. and i am waiting for your next post keep on updating these kinds of knowledgeable things.

I had been very encouraged to find this website. I desired to thanks with this special study.

Hey,

Great articles. Looks like I am reading after long time but very interesting. Thank you very much.

We can now see that Michelangelo was a master and made this masterpiece that stands until these days, but as everything with time things start to deteriorate, and we can get a taste of what Clemente Papi had to do and the complications he encountered. Great article i love to read these kind of things. Keep up the great work.