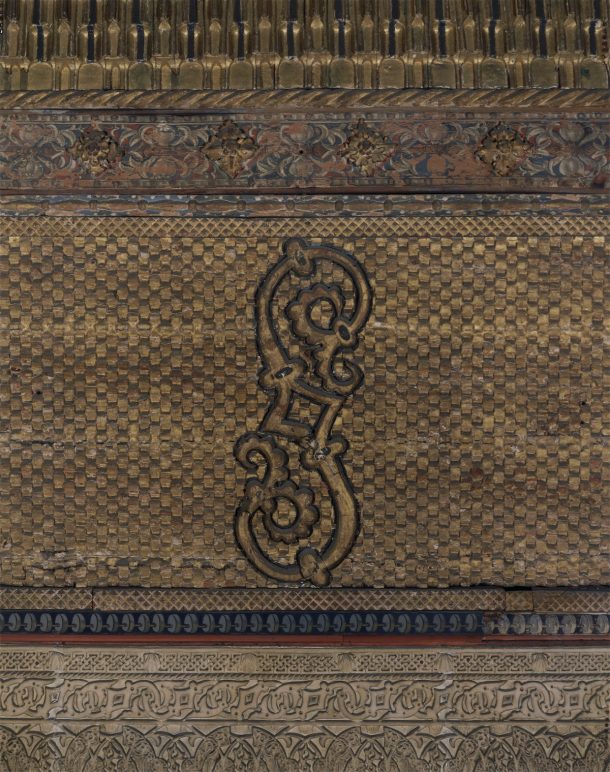

One of the hidden treasures of the V&A’s collection is a spectacular carved and gilded wooden ceiling measuring 6 metres by 6 metres, which came from a palace in the town of Torrijos, not far from Toledo in central Spain.

The ceiling bears the coats of arms of its patrons, Gutiérre de Cárdenas (d.1503) and his wife Teresa Enríquez (d.1529), important members of the royal circle of Ferdinand of Aragón and Isabella of Castile, the Catholic Monarchs. In fact, Gutiérre arranged to introduce Ferdinand and Isabella for the first time, and when asked by the queen which one among a group of men was Ferdinand, Gutiérre replied ‘Ese’, ‘That one’; for this, he was awarded the distinction of adding a floriated ‘s’ (ese in Spanish) to either side of his coat of arms, just as it appears on the ceiling.

Gutiérre and Teresa married in 1490, and the ceiling probably dates to soon after their marriage, making it an early datable example of the type of geometric strapwork construction that was used to create it. It is one of four ceilings that came from the palace the couple constructed in Torrijos. Built around a courtyard, it had four corner towers, inside each of which was a ceiling of this kind, all different though sharing the same stylistic elements. The all-over design of eight-pointed stars, emanating from a muqarnas boss at the centre, is combined with more Gothic elements, in particular the spikey plants inside the geometric framework. These also provide the background to the coats-of-arms in the corner ‘squinches’, and are probably thistles, punning on the name Cárdenas, which relates to the Spanish word for thistle.

The ceilings’ aesthetic is telling of the taste for Islamic styles among the elite of Iberian society, during a historical period which coincided with the campaign against the Nasrid sultanate of Granada – this eventually surrendered in 1492, bringing an end to more than eight centuries of Islamic rule on the Peninsula.

By 1900, the Torrijos palace was in a ruinous state. A Spanish publication of 1902 presents a walkthrough of the building and its richly decorated interiors, describing the four ceilings and other precious elements still in place. The article explains that the present owners have put the palace’s ‘cupolas and paintings, as well as its beautiful patio, up for sale’, and that ‘distinguished persons and aristocrats have rushed to acquire these ceilings and adornments’. Indeed, it urges ‘lovers of antiquities not to miss this occasion on which for a very low price they might display in their homes jewels of such merit and antiquity as those described in this article’. Regrettably, the palace was eventually demolished in 1917.

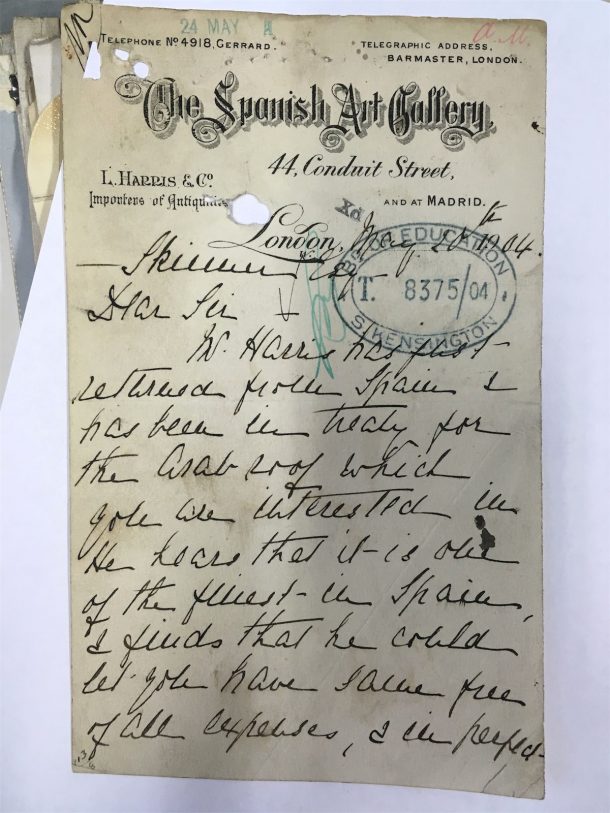

One of the ‘distinguished persons’ who ‘rushed’ to procure a ceiling was Lionel Harris (1862 – 1943), proprietor of The Spanish Art Gallery, an antiques dealer based in London and Madrid. He sold many Spanish works of art to the V&A during the early decades of the 20th century, and in 1904 he approached the museum with the offer of a ceiling from the Torrijos palace. From the limited documentation that survives in the museum’s archives, it seems he had already invested in the cost of transporting it to London, as well as ‘repairing all defects’.

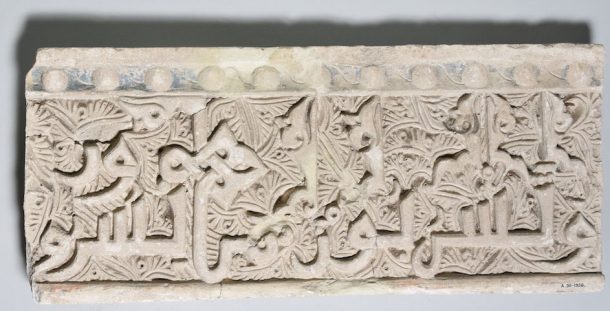

The ‘reasonable price’ being asked for the ceiling was £480, but almost the same again in order to recoup the shipping and other preparation costs, totalling a purchase price of nearly £70,000 in today’s terms (calculated according to the National Archives’s currency converter). The museum’s acquisition committee inspected the ceiling in person in December 1904, and the art adviser Walter Crane declared it ‘a truly magnificent specimen’. The plaster frieze that ran around the walls below the ceiling was still in place at that date, being too fragile to extract from the wall, and the V&A requested that moulds be taken so that it could be reproduced by plaster casts. Nevertheless, there are four sections in the V&A’s collection that seem to be part of the original frieze – two of these may have been the ‘portions of plaster work presented by Messrs. L. Harris on 30th July 1909’ according to the museum’s documentation.

Over time, the other three ceilings came to be acquired by the Museo Arqueológico Nacional in Madrid; the Château Villandry in the Loire Valley, France; and the Museum of the Legion of Honor in San Francisco. These will all be the subject of future blogs in this series. The V&A’s ceiling was accessioned under the museum inventory number 407-1905, and installed above the apse end of the Raphael Cartoon Gallery – where the great Altarpiece of St George stands today. This end of the gallery was separated off by a curtain, creating a small lecture theatre behind. One former V&A curator recalled attending Union meetings in that room, and gazing up at the Torrijos ceiling during the boring bits! If you remember seeing the ceiling when it was installed in this location, please do let us know by posting a comment below or sending us an email – we would love to gather your memories!

It may have taken until 1910 for the ceiling to be installed, because when it was next dismantled – in 1993 – two newspaper fragments were found wedged between the timbers of its support structure: The Sporting Life, dating from Thursday 31 March 1910, and The Racing Specialist, 12 April 1910, giving an insight into what the museums’ technicians were reading on their tea-breaks in 1910!

The ceiling was removed from display and packed into 40 large crates, and it has remained in storage until now. Excitingly, the Torrijos ceiling will soon see the light of day again, as it will be one of the large objects displayed at the new V&A East Collections Research Centre in Stratford, east London. The ceiling is currently being conserved to stabilise its surface area (approximately 100 square metres), and to clean it for reinstallation. This provides us with an unprecedented opportunity to study it up close for the first time and to gather as much information about it as we can before its various parts are reassembled 10 metres above our heads.

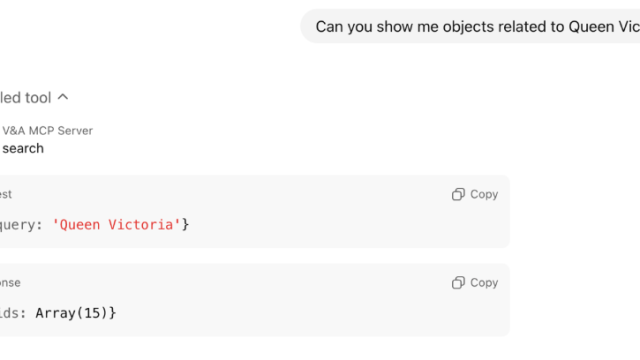

The ceiling’s re-emergence has provided the impetus for the research project we are now undertaking, generously supported by a British Academy/Leverhulme Small Research Grant. This gives us the chance to bring together an international and interdisciplinary group of experts who work on different aspects of these ceilings and their historical and artistic context, and to share and pool information to enhance our understanding of the objects and explore new ways to interpret them for the museum’s publics. We launched the project on 29 April, with an online workshop bringing together colleagues from Spain, Germany, and the USA: curators of the two other ceilings that are in public collections (in Madrid and San Francisco), conservators who have worked on these ceilings and related ceilings in the Alhambra, the Museum für Islamische Kunst in Berlin and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and conservation architects who are experts in the construction of strapwork carpentry.

We shared images and film of our ceiling in advance and were able to livestream from the conservation studio, to zoom in on particular aspects. It was a full and intense afternoon, which was followed by more focused conversations in smaller groups. All of this information we brought back to the conservation studio a month later, to look closely at the ceiling with all these questions and suggestions in mind, and to think carefully about all the issues this object raises. This will be an ongoing task for as long as we have this privileged close access to the ceiling!

Over the years, work has been done independently by the different institutions that hold the four Torrijos ceilings – for example, curators and conservators from the Museum of the Legion of Honor in San Francisco came to study the V&A’s ceiling before it was removed from display, to inform their own project to conserve and redisplay their ceiling in 1998. Now, as we plan our own reinstallation, we are resuming the conversation, to learn from their experience. Local historians in Torrijos have researched the buildings constructed by Gutiérre and Teresa, and we hope to better understand their local knowledge and how it relates to the ceilings and the circumstances of their dispersal. We plan further workshops on different themes, and – Covid-19 travel restrictions allowing – a visit to Torrijos itself, to meet members of the local community and understand the impact that the absence of this building has on them.

There are many questions we are asking and things we are starting to learn. There is evidence of various interventions and repairs to the V&A ceiling – when did these occur? On the back of some of the construction beams we found careful notch marks – what do these mean?

Our expert collaborators usually study ceilings in situ, where the backs cannot be seen – we will have to document these marks carefully as we examine other panels, and map them to the front, to see if they relate to particular aspects of the decoration. Our colleagues who specialise in strapwork carpentry ceilings have suggested that gilded mouldings which emphasise the eight divisions between the inner sections could have been added to conceal losses in the structure that can only have occurred when the ceiling was moved. But these mouldings are datable stylistically and technically to the late 15th century, the same date as the ceiling.

How might this have come about? Was the ceiling originally conceived for one room of the palace – or for another palace altogether – and moved soon after to a new location? There is evidence of the reuse of timbers from other carpentry projects, possibly other ceilings – was this normal practice in a busy carpentry workshop?

What pigments were used in its decoration? We have taken samples that will be analysed. The four plaster panels which might be part of the original frieze – are they? How does their material composition relate to what we know of earlier architectural plasterwork in Islamic Spain? Are the inscriptions legible? Did the other ceilings also have them originally? The plaster casts were created by the V&A, and pencilled on the back of one is a name, apparently ‘Bill Legge’ or ‘Legget, Foreman’. Can we trace him in the museum’s archives?

We want to consider the four ceilings together. Why are they so different, not just in their ornament, but also in size and shape? The ceiling in Madrid, for example, is a dome – where did this fit in the original building? How do they relate to other buildings commissioned by the couple, such as their palace at Maqueda which still stands? Or to other buildings commissioned by noble families in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries? Indeed, what do we know about the patrons of the palace? What documentation exists in Spanish archives about the original palace and the removal of its contents? Where did the other decorative elements and portable objects from the palace go?

We will use this blog series to share some our thoughts and discoveries along the way so please follow and post your own comments and questions below!

Thank you for preserving this magnificent work of art! I just have one question. Was this ceiling perhaps crafted using the art of Intarsia, also known as Kündekari art? I’m asking because I couldn’t find information about this in the article!