Constructing a canonical history of the architectural model is problematic, not least due to the often ephemeral nature of the materials used and their iterative role within the design process, with a corresponding lack of value placed on their maintenance and storage. While prestigious display models are more likely to be spared the vicissitudes of preservation, working models by means of which the “thinking through” of the architect(s) might be accessed often meet an inconspicuous end. These losses, along with the disparate valuations of models in different cultures and practices, create lacunae in the scholarly record and have led to the architectural model being ascribed a place primarily in the annals of western modernity. While it may be agreed that the practice stretches back to antiquity, those belonging to the Islamic East have largely been consigned to the margins because – despite textual references to their existence and use in the Ottoman Empire, at least – they have left no immediate material traces.

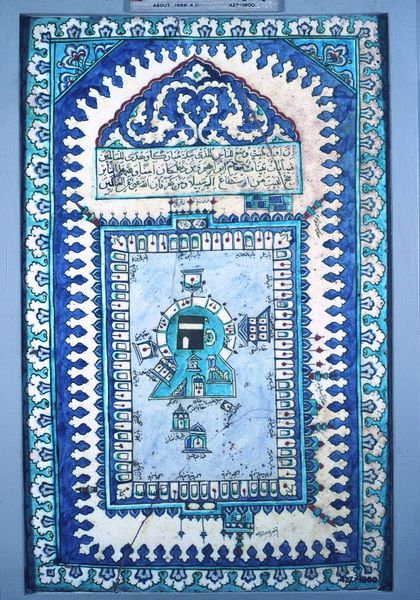

In 1611-12 a 1:1 model of the Kaʿbah was constructed to test a golden drain ordered by Sultan Ahmed I to replace an older silver one, before it was sent to al-Masjid al-Ḥarām in Mecca. This instance, recounted by the 17th century historian Naima, is one of a number of textual references to the use of architectural models in Ottoman design. Within these textual accounts architects seem to work at different scales, such as the Grand Vizier’s use of a wooden model installed in an emptied pool in the gardens of the Topkapı Sarayı in Istanbul to demonstrate to Sultan Mahmud I, in 1740, the layout of the Castle of Belgrade. Early 16th century expense registers seem to reference materials purchased to make architectural models and later documents discuss models intended both to inform construction and to secure approval from the sultan, such as the plan and model for the Fortress of Izmail (Ukraine), both of which were presented by the master of works, Seyyid Numan, in 1793-4. Such textual references seem to imply not only varied scales but differentiated roles for models within the design process and presumably different levels of finish. Gülru Necipoğlu-Kafadar has suggested that thinking three-dimensionally was perhaps a more naturalised way to conceptualise and communicate design among Ottoman architects and builders, given the conventional strictures of two dimensionality that were often applied to drawing and painting equally, including architectural renderings.

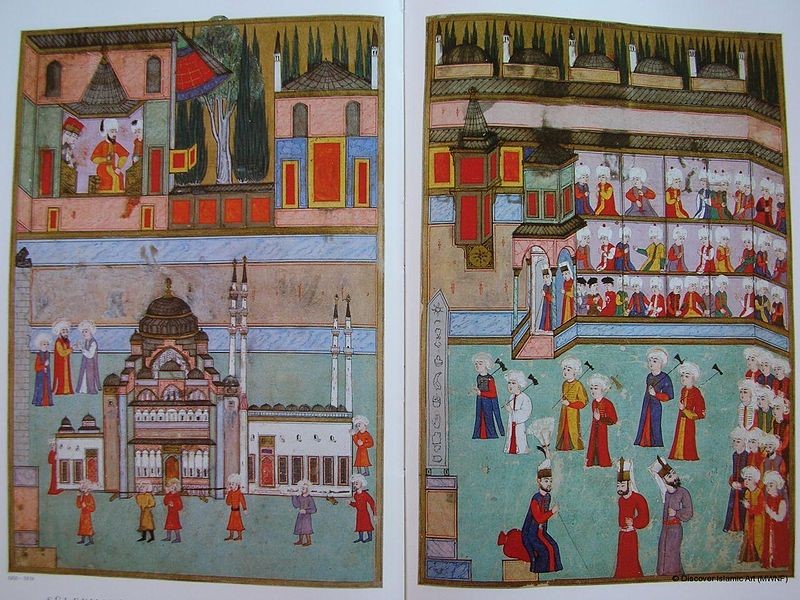

In 1530 Matrakçi Nasuh was tasked with creating two paper castle models for a royal circumcision ceremony in Istanbul. Such references, along with tantalising descriptions of Ottoman garden pavilions made from sugar for festive occasions, insinuate a culture conversant with ephemeral three-dimensional renderings of architecture to convey ideas and impact the onlooker. The large model of Süleymaniye Mosque carried in procession by guild workers for the circumcision festival of Prince Mehmed, son of Sultan Murad III, in 1582, and now represented in the famous Surname-i Hümayun in Topkapı Sarayı, has often been considered evidence of architectural model making. While a commemorative function for the model is likely, it seems reasonable to suggest that similar models in more humble media were made in advance of large projects at this date also, to explain those things that the two-dimensional nature of Ottoman drawings could not.

Wider evidence of thinking through making can be observed in Ottoman objects and texts. The use of micro architecture on objects such as Quʿran boxes and minbars speaks to the high esteem placed on the symbolic use of miniature architectural forms in the Islamic world, and also a practical dialogue between craftsmen and the built environment. Architectural elements in reduced form in stone or wood within larger buildings, such as the bird palaces found on Ottoman mosques, speaks to a culture conversant with developing ideas in three dimensions and with architectural experimentation through kinetic learning. The forms employed were not often commemorative in nature but rather partial and metaphorical, providing a space for unusual patterns and combinations and unresolved structural forms.

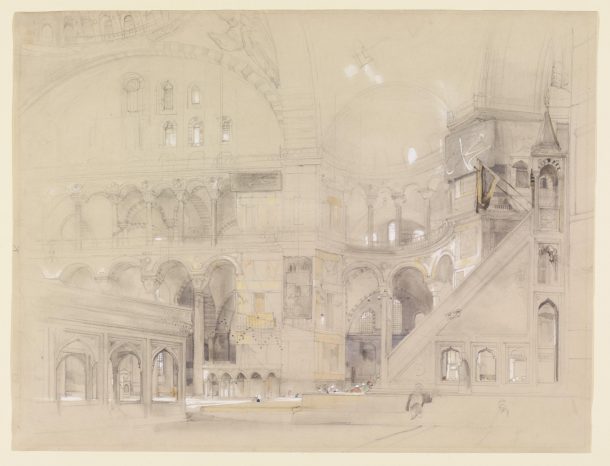

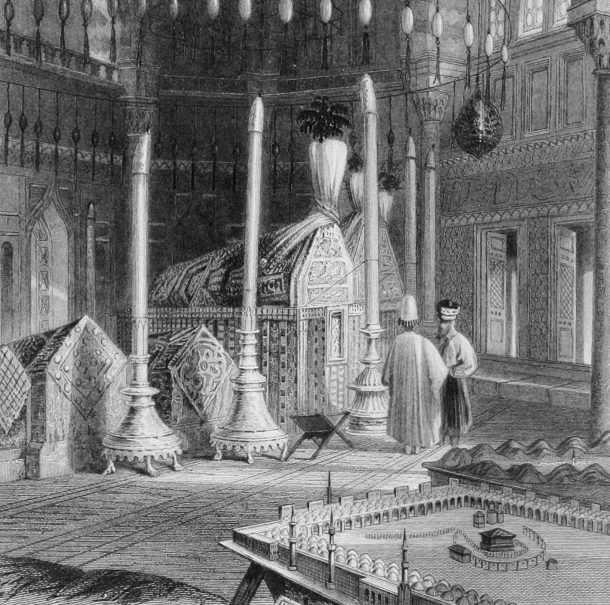

Commemorative architectural models of holy shrines were the most widespread type for the duration of the empire, however, such as the maquette of al-Masjid al-Ḥarām in William H. Bartlett’s sketch of the interior of the Mausoleum of Sultan Suleyman. In the later Empire, increased material evidence survives for the commemorative use of architectural models in the luxury versions given as gifts to sultans, such as the silver model of the Izmir clocktower which was presented by the municipality of Izmir to Abdülhamid II to celebrate the 25th anniversary of his accession to the throne. Textual references to architectural and festive models, along with highly proficient commemorative models, all indicate a culture conversant with thinking through models and with the technical expertise to do so.

The visceral response that microcosms of the built environment engender in their viewers and handlers has meant that architectural models have remained popular: the emotional appeal of the presentation model still persuades today. Scholarly priorities privilege the process of seeing, knowing and creating on the part of the architect. Physical models and the indexical traces of the architect and creative process that they retain are without question decisive – but perhaps historical traces of architectural modelling in texts, objects and buildings should be elevated in terms of their scholarly weighting for a consideration of the development of architectural model making on a more global scale.

To find out more about the network visit our project page.