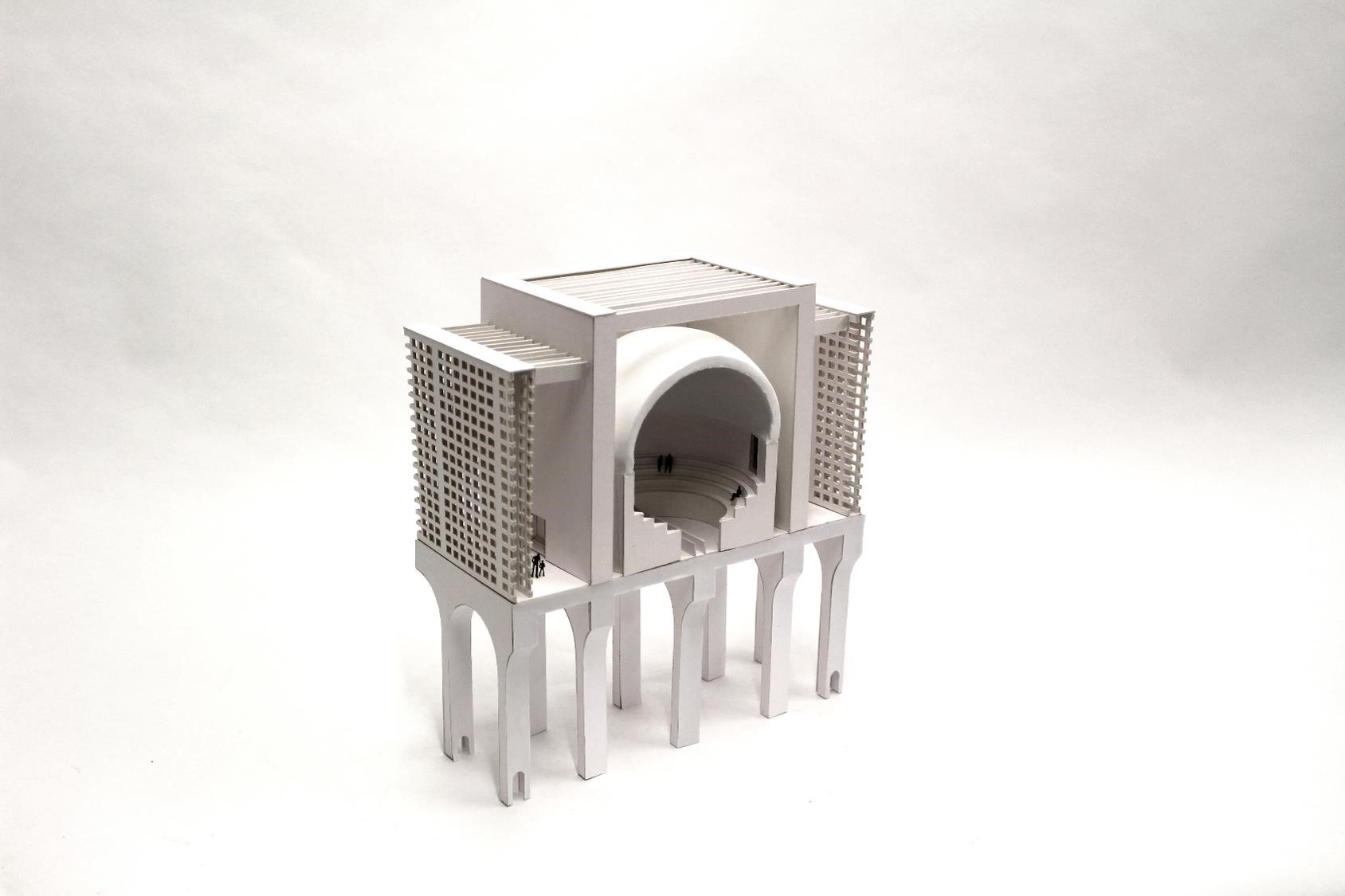

Entering the world of architectural education as a trained modelmaker requires a certain level of adjustment. Commercially, the profession demands a high level of accuracy to meet client needs that range from detailed technical aspects to the high-end aesthetics. When working in education, much like the interaction between the modelmaker and client, the exact output is discussed between Tutor-Technician and student based on the requirements of the task at hand. In contrast to the majority of practice, students then embark on periods of testing and exploration, a luxury that many practicing architects and commercial modelmakers find difficult to implement due to ever tighter deadlines and budgets. In both cases, I have found that many of the questions posed remain the same: how much will it cost? What is the correct scale? What is the appropriate material to choose? What methods should I employ? How long will it take? What is the ‘best’ or quickest way?

The list goes on.

All answers are circumstantial and, given the scope of specialisms that are cloaked under the title of ‘Architect’, can lead students down any number of roads with regards to their exploration and interest. What I notice, and feel is visible in many professions and in everyday life is a desperation, impatience and need for immediacy in the results. Digital manufacturing technology is often recognised as the answer to this and, as a result, has increased expectations of fast paced design work.

In the same vain, it has raised questions about the value of using physical making to the learning process. Recent independent[1] and practice-led exhibitions in the UK[2] and Europe[3] show that there remains a strong wide spread investment in modelmaking. These displays presented the value of recording and communicating these steps of thought alongside completed designs made in a variety of mediums, new and old.

The modelmaking workshop both professional and educational, would undoubtedly be branded outdated if it neglected to employ the use of computer aided design equipment. It presents both opportunity and problems for the development of those wanting to grasp the various aspects of the existing and future built environment. The outputs and accuracy can be extremely beneficial and help to project design ideas quickly and in previously unrealised directions. New students embarking on modelmaking tasks gain a certain satisfaction from observing an idea take shape in the hands of a piece of technology, a process that can be captivating to observe.

From the perspective of an educator, this equipment can also present pedagogical challenges. Laser cutters, additive manufacturing and CNC machines will only produce a product from the design input a user provides. The various machines that deliver on the manufactured concepts rely on good data to deliver quality results. All too often this data is only linked to facts and figures, and less to the experience gained through the human touch of the designer themselves. I see it as essential to ensure that the lure of digital tools remains evenly balanced and doesn’t cloud the value of the broader learning-by-making experience.

Architectural education in the UK is on the cusp of some potentially big changes to its teaching structure, which currently – within the RIBA system – can stand at 5 years taught and 2 years in practice at a minimum, among other routes to becoming a qualified architect. Streamlining the learning process appears to be the vision for the future, with digital manufacture expected to take on the majority share of the workload when it comes to physical outputs.

From my point of view there seems to be less and less provision made for practical learning. Yet, as making remains a popular activity for a huge portion of current and prospective student interests, I firmly believe the retention of this mode of learning is essential in all schools. The missing factor is often an adequate time allowance for students to be truly explorative as submission dates loom, something curriculum planners need to be more conscious of.

As a mode of learning, modelmaking will always involve an expenditure of time, materials, waste and a varying amount of money. Gaining experience of this process can directly inform a better understanding of materiality and working considerations when setting out to design and build at any scale. Time engaged in making can also play a key lesson in raising the awareness of the environmental impacts of construction and its by-products, which can be carried forth into practice.

The true value of modelmaking weighs heaviest during the journey in which collecting skills, both practical and digital, can inform us of the possibilities and equate to a wealth of experiential insights in their own right. This strengthens an individuals’ ability to choose the most appropriate tool, process or medium and discuss ideas with a level of first-hand practical experience. These are valuable skills for any up and coming designer/maker.

When teaching new architecture students in the use of modelmaking, we must therefore instruct on not just what is at the cutting edge of making technology, but also what is established, proven and refined. By doing so effectively, students are able to identify from as wide a net as possible and the best conclusions available in terms of design, end-usability and ever increasingly, environmental impact. As the face of architectural education changes in the UK, tactile cognitive values must be upheld to maintain a well-informed skill set for our graduates. Bridging the gaps between professional modelmakers and tutor-technicians, we should continue to encourage small scale modelmaking to learn the principles of the 1:1, not just in the end product, but crucially through the mistakes made in order to produce them.

To find out more about the Architectural Models Network visit our project page.

For more on the modelmaking workshop see here.

1 – Architecture Prototypes and Experiments (2018) [Exhibition]. The Aram Gallery, London, UK. 2 August – 3 September 2018

2 – Renzo Piano The Art of Making Buildings (2018) [Exhibition] The Royal Academy of Arts, London, UK. 15 September 2018 – 20 January 2019

3 – David Chipperfield Architects Works 2018 (2018) [Exhibition]. Basilica Palladiana, Vicenza, Italy. 12 May – 2 September 2018