Object pitch day 2 took place on 12 September and was another successful event showcasing a wide range of objects put forward by members of staff and featuring very different reasons for pitching these objects for the ‘A history of an OBJECT in 100 worlds’ project. This was also a very ‘meta’ session including a lot of self-referential reflection on the methods and aims of the project.

Bill Sherman opened with a reminder about the origin of the project in the context of recent emphasis on object-based research across cultural institutions: rather than looking at objects as a vehicle for global history, the emphasis here is on what a particular object is and does, and the aim is to unpack the different stories that an object holds and can tell by looking at it from as many perspectives as possible.

OP2/01

Andrew Lewis, content delivery manager in the Digital Media department, explained that in order to choose an object that could give the number of stories required he started by defining a brief:

The object had to 1) be indicative of the breadth of Museum’s collections; 2) be linked to cultural memory, the ways in which we record it and the implications of these methods; 3) be an object that has mass impact that touches lots of people throughout their lives (as opposed to a big iconic art object that doesn’t really affect people in their everyday lives).

This suggested an imaginary object that he called ‘the personal memory machine’, which he felt would encapsulate “many themes of many exhibitions that have been shown here”; and he found an object in the collection that fits the bill: the Kodak Brownie box camera.

- ‘Popular Brownie’, camera, Kodak, Eastman Kodak Company, 1950-1959. Museum no. B.12-2004 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

This mass-produced object exemplifies the transformation of photography from the exclusive domain of a few trained experts to an activity that anyone could engage in, and its box shape, Andrew proposed, symbolises all the different worlds it can open up.

These include the metal and leather trades because of the materials from which it is made, and take in the history of image-making, from various techniques of realistic representation before the advent photography to the transformations in visual communication and graphic design made possible by the technology. But its biggest impact, he argued, is in the field of product design, as it progresses through many incarnations, including Polaroid’s self-developing instant film cameras (allowing for the rise of the “dual selfie in dodgy act”); the slick 1960s Brownie ‘Vecta’ model, a beautiful object that is also part of the V&A’s collection; the first digital camera – with a cassette! – invented by Kodak in 1979, which at the time didn’t really take off because it’s essentially a large computer-shaped object; all leading to contemporary digital technology’s most ground-breaking development: the ubiquitous tablets and phones that are pocket cameras and computers for anyone who can afford them.

a beautiful object that is also part of the V&A’s collection; the first digital camera – with a cassette! – invented by Kodak in 1979, which at the time didn’t really take off because it’s essentially a large computer-shaped object; all leading to contemporary digital technology’s most ground-breaking development: the ubiquitous tablets and phones that are pocket cameras and computers for anyone who can afford them.

Andrew neatly illustrated the social impact of these devices by comparing two photographs by Associated Press of the last two papal coronations (2005 and 2013), the latter showing a sea of glowing camera-phones held up by spectators who are now also documenting the event in real time: these technologies have changed the ways we witness things!

In order to highlight their impact on the ways in which we communicate, he then gave the example of his children sending to each other pictures or videos of themselves laughing – a whole new technology-enabled visual culture.

Such objects, Andrew argued, are nevertheless very much linked to their ancestors, as shown by the example of a handheld stereoscope of the kind typically found in Victorian homes whose function has recently been emulated by Google’s ‘Cardboard Project’ virtual reality technology, the combination of an open software for smartphones that allows users to produce 3D panoramas, with a cardboard headset through which they can then experience them as environments by just moving their head around.

- Stereoscope, underwood and underwood, 1901. Museum no. E.27-2000 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

This is how he produced a panorama of the installation of the Disobedient Objects exhibition , which he could then ‘watch’ (as demonstrated in the photograph below) through his DIY cardboard headset.

Such technologies bring up questions about authorship and ownership: “if everyone can take a photograph who is actually curating? Who is the artist? Is it Horst, or people working with things of his that they’ve got?” “For all of these and many other reasons”, Andrew concluded, “this is the object that I have chosen!”

OP2/02

Geoffrey Marsh, director of the Theatre & Performance department, chose an object from Word & Image: a very large seventeenth century oil painting that goes under the extraordinary title of ‘The Ommeganck in Brussels on 31 May 1615: The Triumph of Archduchess Isabella’. The object has recently been restored by the Conservation department and will be going on display in the new ‘Europe 1600 – 1800’ galleries due to open in April 2015

- ‘The Ommeganck in Brussels on 31 May 1615: The Triumph of Archduchess Isabella’, Denys van Alsloot, Belgium, 1616. Museum no. 5928-1859 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Rather than going through detailed information about the object that one can easily look-up online, Geoffrey said he would like instead to discuss “the nature of this thing as a fragment, a figment, and as the unicorn that is in it”.

This project, as he sees it, is about ‘what is truth?’ The V&A, he explained, has traditionally held the view that there is one truth about an object, which is represented on a label in its case, whereas this project suggests having a hundred labels in the case or possibly more, raising all sorts of intellectual issues about the role of curators: “are curators the people who know the truth and tell it to the visitors – who are not allowed to comment – or are we moving, as Andrew has just illustrated, into a world where everybody’s opinion counts and in fact the role of the curator, in that traditional sense, is coming to an end?”

This painting is the fifth in a sequence of six paintings commissioned by the Archduchess Isabella for her palace in Tervuren, each depicting a section of the 1615 Ommegang procession in Brussels in honour of the crossbowmens’ guild.

sometime in the past; the third and fourth are lost; and the sixth, representing the city fathers and magistrates followed by the religious orders and the clergy escorting the miraculous image of Notre-Dame du Sablon, is also held at the Prado.

Geoffrey listed some of the things this particular section, showing the Archduchess as the central figure of the procession, touches on, including period iconography, the nature of power, Renaissance themes, classical mythology, local ceremony, imperial prestige, religious tradition, civic space, performance and street entertainment, amongst many others.

The detail he chose to pick on today is the image of the unicorn because of its symbolism in the Medieval and early Renaissance, particularly in Christian iconography, which has to do with the nature of truth – think “Quid est veritas?” (John 18:38) or “But is the unicorn a falsehood?” (Umberto Eco, ‘The Name of the Rose’).

![‘The Ommeganck in Brussels on 31 May 1615: The Triumph of Archduchess Isabella’ [detail], Denys van Alsloot, Belgium, 1616. Museum no. 5928-1859 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London](https://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Omm2_4882a86d96f0c084637daded368ddeef-610x458.jpg)

- ‘The Ommeganck in Brussels on 31 May 1615: The Triumph of Archduchess Isabella’ [detail], Denys van Alsloot, Belgium, 1616. Museum no. 5928-1859 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

This Unicorn is a wicker-work figure, a traditional performance form from the area, straddled by a dwarf. To make his point, Geoffrey drew our attention to two wicker-work camels preceding the unicorn in the procession, then to four live camels in the foreground of the scene: “so what did people think at the time? They can see the real camels and the wicker-work camels and they see a wicker-work unicorn. Did they really believe in it?” This, he felt, went to the nature of what this project was all about: “What do we actually believe in about all the stuff we collect? Is it all fiction? Are we just entertaining ourselves and a few of our friends who come here or do our collections have any meaning at all?”

![‘The Ommeganck in Brussels on 31 May 1615: The Triumph of Archduchess Isabella’ [detail], Denys van Alsloot, Belgium, 1616. Museum no. 5928-1859 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London](https://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Omm3_18688cea1b1413ed62a7dcee28722dcb-610x457.jpg)

- ‘The Ommeganck in Brussels on 31 May 1615: The Triumph of Archduchess Isabella’ [detail], Denys van Alsloot, Belgium, 1616. Museum no. 5928-1859 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

![‘The Ommeganck in Brussels on 31 May 1615: The Triumph of Archduchess Isabella’ [detail], Denys van Alsloot, Belgium, 1616. Museum no. 5928-1859 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London](https://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Omm4_9706a11507932e3c5ed7ec131a0c83b0-610x457.jpg)

- ‘The Ommeganck in Brussels on 31 May 1615: The Triumph of Archduchess Isabella’ [detail], Denys van Alsloot, Belgium, 1616. Museum no. 5928-1859 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Geoffrey then moved to a ‘bigger picture’ case for the object: it is absolutely unique even in its fragmented state, it has unquestionable global status, it touches on every section and department in the V&A including conservation who have just been restoring it, it offers the opportunity for a completely interdisciplinary approach (he actually produced an excel sheet listing a hundred essays that can be written on it!), it has a significant anniversary coming up in 2016, it is fascinating in terms of the revival of traditional parades (like Lord Mayor shows) that have become part of the modern tourist industry, and it is very much about the making of modern Europe with Brussels’ current status as the power-base of the European Union.

His main reason for choosing it, Geoffrey ended by saying, it that “this painting, more than any other object in the V&A, explains why we, in this room and in this country, are where we are at today. So it’s great that from April we’ll be able to see it every day!”

OP2/03

For the third pitch of the day, Sonnet Stanfill, fashion curator in the Furniture, Textiles & Fashion department, said that her strategy was to propose an object that is ubiquitous in its function but that is rendered, through its design, a quintessential V&A object: the pair of Oliver Goldsmith ‘Jester’ Sunglasses.

- ‘Jester’ Sunglasses, Oliver Goldsmith Eyewear, Britain, 1954. Museum no. T.243C-1990 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

This object, she argued, is an example of design that encompasses the moment when eyewear went from being a medical necessity for vision to becoming an item of fashion that still fulfilled this function with prescription glasses and sunglasses. The story of this particular pair, she continued, touches on a wide range of themes and approaches.

The story of the Oliver Goldsmith company is interesting in terms of business history: founded in the 1926 by a family of Jewish immigrants, it is an archetypal ‘family business’ of London manufacture spanning half a century across three-generations from founder to grandson. The business is still family run and is still selling its spectacle and sunglasses frames around the world.

The Goldsmith family set up shop on Poland Street in Soho, where they remained until the company closed in the 1980s. Its location, no 20 Poland Street, Sonnet informed us, in now a mozzarella bar. Such thinking in terms of civic progression, tracing the transformation of the shop-front over time, suggests a changing view of London as part of the story.

This pair was made under the aegis of the ‘middle’ Goldsmith and exemplifies a trade that is now lost: the hand-crafting of eyewear. The company manufactured entirely by hand until the 1970s, all in the Poland street workshop.

- Photo of the workshop where the frames were made by hand. In this photograph, taken in 1966, you can see the stacks of orders waiting to be processed.

The Oliver Goldsmith company archive is part of the V&A collection and was donated by the grandson of the founder in memory of his father, Charles Goldsmith, who designed this pair. It consists of around 70 pairs of eyeglasses, including reading spectacles and sunglasses, as well as family photos of the various members involved in the business.

“Another bucket” that Sonnet suggested we could “dive into”, is the history of plastics in terms of technology and as a conservation problem due to the difficulty of keeping them viable as museum objects. The ‘Jester’ sunglasses were made in 1956 at a time when tortoise-shell and wire-rimmed frames were becoming a thing of the past, and eyewear companies were starting to embrace plastics because of their lightness, the scope for whimsy that they presented as shown in this design, and the myriad colour possibilities that they offered. This pair was cut by hand from a slab of clear plastic to which colour laminate was then applied. The company experimented with different ways of achieving such fanciful results and the different styles produced are testament to the enthusiasm that plastic as a material was generating, particularly in the years after the war.

A medical history perspective on these glasses would include developments in optical science and the evolution of the optical trade resulting from the medical profession’s improvements in the testing of eyesight. Another rich avenue to explore would be the themes of vision and perception, moving away from a literal interpretation of the object to something more thoughtful and poetic, perhaps, Sonnet suggested “by asking writers, poets and playwrights to discuss these themes in relation to this pair of sunglasses”.

Confessing that she had probably “forgotten a few buckets”, Sonnet concluded by saying that these sunglasses “are so charming and so whimsical, they were reproduced in all kinds of marketing material, and they represent a larger collection of Oliver Goldsmith eyewear held in the V&A. So vote for me!”

OP2/04

The image was greeted with giggles before Jo Norman, curator on ‘Europe 1600-1800’ in the Fashion, Textiles and Furniture department, even started speaking about the object she was pitching –

- Statue of the head of an ox on a tree trunk, Italy, 1650-1700. Museum no. 60-1882 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

“Your responses are pretty much why this is my object”, she explained, “it is just so weird and it is the kind of thing that either draws everybody to it or repels everybody”. But, there were other reasons for choosing it.

The statue will be the first object to greet visitors of the new ‘Europe 1600 – 1800’ galleries, placed within a context of collecting, specifically in relation to collectors’ cabinets, the forerunners of museums. It therefore seems, Jo suggested, “to be absolutely at the heart of what we do”.

The piece was acquired in 1881 for two reasons. First, Jo explained, as a piece of fine Italian sculpture of that period: the combination of carved marble – the head of the ox which is just about life-size – with carved and painted wood – the peculiar stand representing a tree trunk with the skin of an ox wrapped around it – is a clear testament of its unknown maker’s virtuosity.

The main reason for its acquisition, however, is its status as a natural curiosity. Its story, which came up when it was acquired, dates back to the 17th century. In the 1660s, a monastery bought two oxen to be fattened up and eaten. One of them didn’t fatten up as it should have, and when it was eventually sent for slaughter in the monastery’s kitchens, a growth was discovered inside its head and was thought at the time to be a petrified brain. Various scholarly articles were written about it between 1670 and 1710, the latest disproving the theory that it was a petrified brain and suggesting instead that it might be a boney growth. The object has remained the subject of scientific and intellectual debate throughout its museum history. It was examined by the Natural History Museum in the 1930s, confirming that the growth is organic and was probably part of a whale or an elephant or some other larger mammal; and it has recently been examined again as part of the conservation process.

In this way, Jo said, “it encapsulates the closeness of the relationship between art and science, both as part of the classification of knowledge in the 17th century and as something that is still very much active today”.

![Statue of the head of an ox on a tree trunk [detail], Italy, 1650-1700. Museum no. 60-1882 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London](https://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Ox2_ef28d0b9fc0de548fa6cbf6be6a7300c.jpg)

- Statue of the head of an ox on a tree trunk [detail], Italy, 1650-1700. Museum no. 60-1882 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Finally, as Jo demonstrated by pointing at the detail photo, it is absolutely filthy; and the reason it is filthy is because so many visitors come through the gallery and stroke it. “It is something that inspires revulsion, that sense of it being a freakish thing that nobody quite understands; it inspires a huge amount of curiosity and it inspires quite a lot of affection as well.” This way in which it draws together different responses, both intellectual and emotional, is the reason she’s chosen it as her object.

OP2/05

Beth McKillop, deputy director of the Museum, said that for her pitch she wanted to talk about an object that had long intrigued her, an object that “reverberates in different worlds”: the Luck of Edenhall.

- ‘The Luck of Edenhall’, beaker and case, probably Great Britain, possibly Egypt, possibly Syria, c.1350. Museum no. C.1 to B-1959 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

It is a glass beaker with enamelled decoration in stunningly pristine condition, it is contained in a custom-made snug leather protective case, and it is one of the star objects of the V&A’s Medieval and Renaissance galleries.

Beth wanted to talk about it, she explained, “because it seems to bleed very naturally into multiple worlds, multiple thought systems, multiple histories… multiple magic really.”

The name ‘Luck’ comes from a local tradition whereby placing it in a house called Edenhall in Cumbria was believed to bring protection and good fortune to that house. “This takes us”, Beth suggested, “into a world of non-religious belief, perhaps superstition, of the imbuing of a distant and exotic object with special portent qualities; and it touches in that way on a facet of human interaction with museum objects which we sometimes forget and underestimate”.

It is also an object that speaks about race, about peoples and about identity because it is believed to have been brought to Europe by a Crusader and therefore carries with it that sense of a time when noble ideals were the means of mediating conflict between people of different religious beliefs.

It also holds a number of very obvious worlds in its physical presence: “its delicious glass with its bubbles and its lucid and bright qualities is just a marvel, and the enamelled coloured decoration is also something that lifts the spirit”.

It also leads into the world of logic: how do we know where it was made? How do we know why it was brought back to Europe? How do we know whether the people who believed that it conferred a special protection on Edenhall were correct or otherwise? Logic says if it came back to Europe during the 14th century, then it is a crusader object; but as we all know, in museums we can do analyses, we can date things, we can use the physical qualities of the object to give us an answer with a certain amount of variation for true doubt. “The story that we tell about this object is posited on a set of logical assumptions and I would love to test those and to see people from different worlds colliding and debating where this amazing object came from”.

- ‘The Luck of Edenhall’, beaker and case, probably Great Britain, possibly Egypt, possibly Syria, c.1350. Museum no. C.1 to B-1959 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The beaker’s leather case is itself impressively multi-layered both literally and figuratively. It carries upon it, for example, the Jesuit ‘IHS’ Jesuit moniker, adding a Christian Catholic layer to an object from the Middle East. It speaks of war and conflict in the place with which it’s associated, but also indicates that glass vessels rather than more precious metals were used in church and sacrament in that area.

There’s finally a delightful poetic dimension to the object that Beth evoked by reading lines from Longfellow’s translation of a 19th century ballad by Johan Ludwig Uhland [Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Ballads and Other Poems, 3rd edition (Cambridge: John Owen, 1842), pp. 48-52.]:

As the goblet ringing flies apart,

Suddenly cracks the vaulted hall;

And through the rift, the wild flames start;

The guests in dust are scattered all,

With the breaking Luck of Edenhall!

In storms the foe, with fire and sword;

He in the night had scaled the wall,

Slain by the sword lies the youthful Lord,

But holds in his hand the crystal tall,

The shattered Luck of Edenhall.

Following this reading, she concluded her pitch by saying: “it is a literary object, it is a religious object, it is an object of fantastic physical presence, it has religious, regional and superstitious belief elements to it and I think it would make a fabulous subject for a hundred worlds to come together”.

OP2/06

Terry Bloxham, assistant curator in the Sculpture, Metalwork, Ceramics & Glass Department, brought along her object to support her case: a humble dish, or is it so humble?

With the dish safely propped up on the table, Terry began her pitch: “All peoples, cultures and nations of all ages are united in their use of clay to form vessels for culinary, ritualistic and decorative purposes – so clay is what unites us all”.

This dish, she explained, represents the spread of different cultures over a number of centuries.

It is immediately recognisable visually as a form of Hungarian Germanic decorative ceramic.

It was made in the Tara Barsei region in the province of Transylvania in Romania in the 18th century.

It is fashioned from a light-coloured clay body, covered in a white slip of watered-down clay and freehand-painted in very thickly applied cobalt blue impasto.

Transylvania has good quality clay beds and had, at the time, a large number of family-run pottery centres, each carrying their own centuries-old traditions of decorations. Much of the cobalt used for decoration was mined in Saxony, and the tulip in the middle of the dish reflects an interest in that flower which, as far as we can determine, was first imported in the 16th century from Turkey through the Romanian regions.

This thick blue-on-white decoration is particularly associated with people known as ‘Szeklers’, Magyar settlers who moved into the region in the 12th century when it was absorbed into the kingdom of Hungary. Over the centuries, immigration from different groups continued but each retained their particular culture and language. This also led to cross-cultural influence in their decorative arts, fashion, furniture, and in ceramic decoration. The blue decoration is very characteristic of that Szekler/Saxon intermingling in the Transylvanian region.

When the region came under Romanian communist control in the 20th century, the number of family-run ceramic-making centres decreased and they were replaced by larger centres for mass-produced products. This characteristic blue on white pottery is still proudly produced today, though there is very little handwork going on any more and the blue slip is painted on very thinly so that it looks very flat.

The Village Museum in Bucharest showcases examples of traditional Romanian Szekler and Saxon homesteads, along with their original contents, including decorative dishes such as this one which were displayed high up on the homes’ walls.

To bring this closer to home, Terry concluded, Prince Charles has been supporting endeavours to preserve these craft traditions since his first visit to Romania in 1998, and this particular dish is an example of the richness of this traditional culture on display at the Museum for all to see.

OP2/07

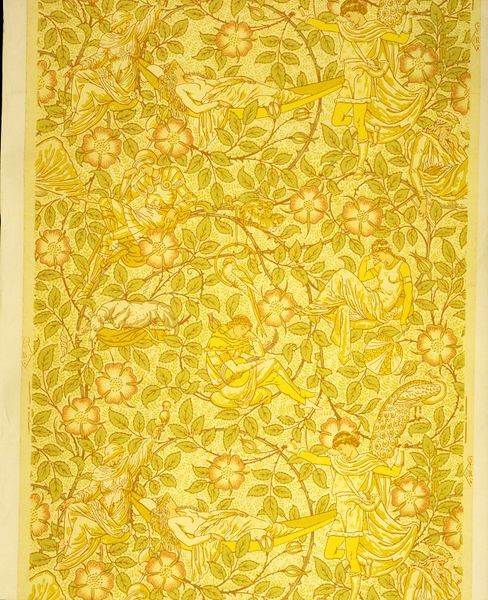

Jo Banham, Head of Adults, Students & Creative Industries in the Learning Department, chose an object that, rather than geographical worlds, touches on worlds of “who used things, who made things, who bought things, and… Sleeping Beauty”: a wallpaper designed by the artist Walter Crane.

- ‘The Sleeping Beauty’ Wallpaper, Walter Crane (designer) Jeffrey & Co. (manufacturer), Britain, 1879. Museum no. E.60-1968 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

This object, Jo explained, is on one level standing in for almost any wallpaper from the V&A’s collection – one of the largest collections of wallpaper in the world, which very few people know about – and a type of thing that few see as a precious object that a museum would collect.

But it is also something that some of us have used in our own homes or will find in many of the houses that we have lived in or visited.

This wallpaper dates from 1876 and reflects changing methods and types of production in the 19th century. It is an object of mass-production even though it is designed by an artist, and it illustrates how something that up until the 1840s was a hand-made luxury product gets progressively taken over by machine production in the 1850s. “To give you an idea of the impact of that change”, Jo said, “production rose form about 1.25 million rolls prior to 1845 to 2.5 million rolls by 1874; and, concurrently, prices fell for the cheapest of machine prints to about a farthing per roll.”

In that way, it was quickly becoming a commodity that almost anybody with any surplus income could afford.

It is a nursery wallpaper produced specifically to be used in the nursery room. The designation of objects for particular room of the home is very much a Victorian phenomenon. It is allied to a host of arguments about the increasing specialisation of areas in the home and the increasing application of gender, age and class differentiations, amongst others – a whole world that can be looked at in relation to this object.

The nursery and childhood are very much inventions of the mid- and late-Victorian period. Prior to this time, children were considered to be to a large extent smaller versions of their adult parents and cohabitants. From around the 1850s and 1860s, objects begin to be produced specifically for the nursery. These are specifically aimed at consumer parents with enough money to spend on things for their children. The associations in these objects would typically be those of innocence, youthfulness and naivety, as well as education and learning. Most of the objects that you will find in the nursery room, will have a huge aesthetic appeal, but will also hold a moral or educational lesson.

This design is based on the well-known Sleeping Beauty story, a very appropriate tale for a nursery, something to help the children go to sleep with. It is by Walter Crane who at the time was the artist most associated with childhood and this new area of the nursery room. He had been producing children’s books for years, and was incredibly successful and popular with this new artistic audience that was interested in children’s cultural and artistic education. Crane began producing wallpaper in the 1860s and by the 1870s was well into his stride as a pattern designer. This allows for talk about the aesthetics of childhood and related objects.

The paper is machine-produced, which is usual for nursery wallpaper because they have a high turnover and need to be replaced pretty quickly. All wallpapers are subject to a lot of discussion about wear and tear and dirt and so on, and for the nursery in particular, it is extremely important to maintain high levels of cleanliness and hygiene.

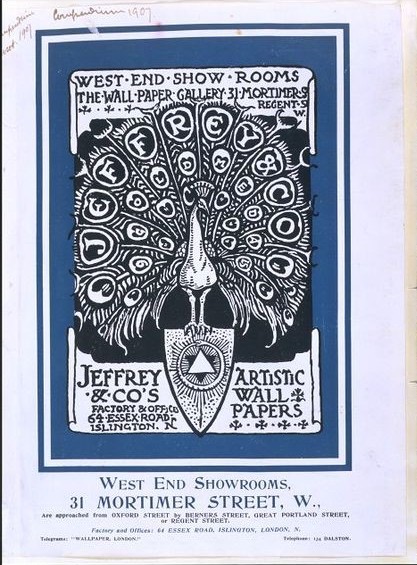

This wallpaper is one of several marketed that year as part of Jeffrey and Company’s artistic range.

- Jeffrey & Co. Album, Jeffrey & Co. (compiler), Britain, 1838-1915. Museum no. E.42A/2-1945 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

As this advertisement image shows, it was part of a new the artistic range of non-arsenical wallpaper! “You not only need to have a clean nursery”, Jo said, “you also have to prevent, if you can, to poison your children”. Producers and manufacturers got on to that very quickly. There was a lot of discussion at the time, in journals and newspapers such as Punch and The Times, of children and invalids who had been badly affected by the decorations around their room, so this introduction of patent non-arsenical hygienic paper was very important and a good selling point. Jeffrey had invited a well-known professor of chemistry to come and test his papers and he proudly declared them all free of any of these noisome substances.

- ‘Jeffrey & Co’s Artistic Wallpapers’ Advertisement, Jeffrey & Co. (manufacturer), Britain, c.1907. Museum no. E.42A/3-1945 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

A final aspect that Jo wanted to point out is that this wallpaper was made by a designer who trained as an artist, and is in that way part of a movement in the late 19th century that sought to involve artists in objects of fairly modest domestic consumption, objects like wallpapers. It is, she concluded, exemplary of the porous nature of the arts, crafts and design at that time, “a fairly fleeting period where for the first time and perhaps the last we get some of our greatest artists and designers involved in producing some of our most humble objects”.

***

Seven pitches putting forward, once again, very different objects and raising new questions around them. Is the best object for this project a common product with mass impact or a unique artefact of exceptional physical presence? What kinds of questions would we like it to pose about the role of museum collections and of the people who work there? Which objects of design are particularly eloquent about the moment or region or circumstances of their making? What parts do intellectual and emotional considerations play in our relationship to museum objects?

Watch this space for the next report on Object Pitch day 3!

![‘The Ommeganck in Brussels on 31 May 1615: The Triumph of Archduchess Isabella’ [detail], Denys van Alsloot, Belgium, 1616. Museum no. 5928-1859 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London](https://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Omm4_9706a11507932e3c5ed7ec131a0c83b0.jpg)