Last October, my sister and I used the mudroom at the back of our home as a staging area for a Thanksgiving meal. Though public health officials in Toronto had advised hosting no more than 25 people outdoors, our group was capped at ten. Guests proactively adorned in masks and woolly layers arrived in our backyard bearing elaborate salads, steaming roast vegetables, and freshly baked sweet and savoury pies. Potluck contributions were arranged on a table in the mudroom with guests invited to identify preferred fixings and then receive plates one-by-one through an opened window – a delivery method not unlike the reactivation of Medieval wine windows in Italy last summer.

Eating outside—in backyards and parks, and on sidewalks and patios—became increasingly normalized last spring after numerous regions clamped down on public and private indoor gatherings. Whereas eating al fresco had once been one of several options for casual dining, the COVID-19 pandemic made noshing en plein air, at least for many, the new default. Al fresco, a term which derives from the Italian words for ‘fresh air’, can refer to myriad dining scenarios. One example, picnicking, an activity hitherto associated with mild temperatures, bucolic settings, and unfussy foods consumed without tableware, remained relatively popular even as temperatures dipped last fall. Meanwhile, depending on local and national rules, eateries and bars were variously allowed to continue indoor service or limited to outdoor service or takeout. While some patrons felt indifferent, or even entitled, to eating indoors and the accompanying higher risk of contagion, others embraced the novelty of new and expanded al fresco dining choices.

In some of the cities that experienced protracted lockdowns and lacked pre-existing al fresco infrastructures, unprecedentedly quick amendments were made to municipal rules. For example, “[l]aunched after a springtime indoor dining ban as the deadly virus started infecting a growing number of Torontonians, CafeTO eventually saw 801 patios across Toronto, including more than 200 in curb lanes closed to vehicle traffic,” reports David Rider in The Toronto Star. In a BBC News piece from October 19, 2020, Sophie Williams writes, “After a popular outdoor dining season, restaurants and bars in the northern hemisphere are facing the dilemma of keeping customers who want to remain outside warm during winter.” Williams gives examples of London and Boston establishments buying yurts and tents and “‘enclosing their patios with plastic and heaters’” for the purpose of “‘extending patio season.’”

As a result of surging commercial and personal interest, many hardware and department stores reported selling out of canopy tents, outdoor heaters, and firepit accessories last winter. Now that the spring thaw is upon us and fewer accommodations are required to enjoy relaxing out of doors, people seem to be feeling a mixture of excitement and apprehension at the prospect of al fresco meet ups. There are, of course, many ways to spend time outdoors with loved ones that do not involve eating. However, as weeks of social distancing turned into months and we’ve now passed the one-year mark, the desire for more traditional means of spending time together has increased, with sharing a meal being an obvious choice. Beyond questions around cultural norms and preferences—not to mention contagion risks—lies an existential query about what it means to bring the indoors outside and whether the pandemic may have implications for eating practices that linger long past mass vaccination.

As reflected in part by the rise of DIY renovations and decorating projects, lockdown has compelled many people to reconsider their relationships to home. At the same time, being banned or discouraged from entertaining has made domestic, interior spaces feel more private. Having moved into a new apartment myself during the pandemic, the irony wasn’t lost on me that the first home I put substantial effort into painting and spiffing up would also be unlikely to host guests or dinner parties for at least a year. As a result, access to outdoor space of any kind has become more and more valuable. While walking past an enviable porch set up a few weeks ago, a friend semi-cynically quipped about the possibility of people beginning to Airbnb their stoops, balconies, and gardens.

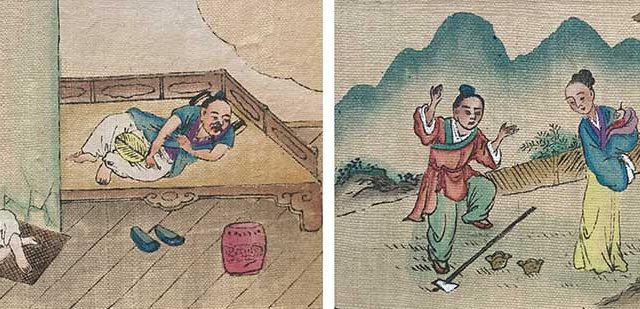

Joking or not, my pal’s comment about covetable outdoor spaces got me thinking about the relationship between al fresco and frescos, the art form that involves “painting water-based pigments on freshly applied plaster, usually on wall surfaces” and often to create a mural. While al fresco connotes feasting or imbibing in the presence of pleasant, outdoor vistas, frescos, such as those in the V&A’s storied Leighton Rooms, were often commissioned to elevate interior spaces by presenting diverting or instructive scenes of human, animal, historical, or spiritual company, the latter sometimes including serious and even macabre Biblical or moral lessons.

Diana Resting, with putto and hounds (fresco), Alessandro Gherardini, Florence, ca.1705 (V&A: 680-1864)

A year into the global pandemic and its attendant varieties of physical and emotional isolation, both real and artful renderings of new settings and company feel all the more valuable. In pre-pandemic times, al fresco dining may have suggested a mode of outdoor repast more refined or intentional than a picnic or pop-up patio in a former bike lane. Today, however, the feeling of fresh air and sunlight – or even bundling up to ward off an evening chill – amidst the company of friends or strangers feels quite appealing regardless of the quality of the foodstuffs or the elegance of the backdrop. Though a multi-course meal overlooking a vineyard or a rooftop reservation at a hot new club still sound chic as ever, the pandemic has revealed how the delights of al fresco dining can be truly democratic.

It feels too soon to say whether voluntary outdoor dining will continue to appeal – or even be a widespread restaurant option – in a post-pandemic future. Adopting a positive, Scandinavian-inspired attitude toward outdoor socializing outside was widely encouraged last winter, yet the phrase “al fresco dining” still conjures a sense of unhurried ease and it’s challenging to imagine groups voluntarily gathering outdoors during inclement weather. Suffice it to say that rolling changes to urban al fresco dining options have invited past and future clientele to reconsider the role of restaurant culture and to reframe expectations of comfort, formality, accessibility (fiscal and physical!), and convenience. As restaurants crept outside and picnics became more status quo last year, appreciation for the social and sensorial pleasures of gathering to eat, wherever we can, has only grown.

Related objects from the collections:

‘Al Fresco’ (Illustrated music sheet cover for Al Fresco Polka), Colour lithograph by T. Packer, , ca. late 19th century – early 20th century, (V&A: S.2739-1986)

‘A family picnics under the cherry trees, Kyoto’ (photograph), Herbet George Ponting, ca. 1904 (V&A: E.60-1993)

Glyndebourne (print), Sue Macartney-Snape, London, 1990s (V&A: S.1735-2014)

‘Picnic Group in Nasib Bagh, India’ (photograph), Samuel Bourne, ca.1863 (V&A: 52982)

Small Hamper Biscuit Tin, Hudson, Scott & Sons, c.1900 (V&A: M.744-1983)

‘Group at a Spanish Cafe, Gibraltar’ (photo), Francis Frith, 1850s to 70s, (V&A: E.208:3911-1994)