This a special guest post from Alice Baddeley, Volunteer Assistant Curator at Coventry Transport Museum.

When I started thinking about our collection and the way in which the pandemic has shaped our understanding of those objects, I immediately thought of the 1938 Eccles Caravan. Owned by the Guy family for 38 years, the caravan was a treasured part of their lives, revealed in part by their logbook which records the care and joy they took from it. Traditionally, the caravan was a way for families to ‘escape’ to rural spaces cheaply and symbolically, they still evoke leisure time with family, holidays, and travel.

Today, however, mobile homes have become a point of contention within the lens of the pandemic. During the national lockdown people reassessed the value of green spaces as not only beneficial for physical and mental health but also as a safer space to be than densely populated urban areas. The false perception of the isolated countryside became linked to escaping the stresses of the pandemic, with caravans a way to be ‘safe’ in ‘unsafe’ situations. The limited interior of a caravan and its self-containment also allows for greater control over sanitising and cleaning surfaces and was used, in some cases to quarantine family members from the rest of the household. In this way, the leisure vehicle was imbued with new urgency and gave back a sense of control. While these features eased the anxieties of caravan owners, the actions born from it, such as taking their vehicles out to campsites – along with city dwellers retiring to second homes in the countryside – created a feeling of discontent amongst local communities outside of urban centres.

This discontent was perfectly encapsulated by Dominic Cummings’ drive to Durham in April which prompted a public outcry. Earlier, CaravanTimes.co.uk, an online caravanning community, had published an article on 16 March 2020 encouraging readers to ‘escape the corona hysteria’ (sic) by taking their caravans to campsites for the duration of the national lockdown. Just days later, news outlets reported people travelling to rural areas such as the Scottish Highlands and areas of Wales in ‘well-stocked camper vans’. In a strikingly similar tone from May 1939, The Motor described the Eccles as an ‘emergency retreat’ from an ‘outbreak of hostilities involving the bombing of our big cities’. This positioning of caravans as emergency shelters echoes their new significance during the pandemic. However, for local, rural communities the sudden influx of people during the crisis caused great concern for local infrastructures and the understandable fears of potential transmissions of the virus. Hostile signs directed towards these groups were placed up around campsites and in villages. The caravan then becomes both an object of derision to some as well as highly desirable to others.

During the summer months, the interest and sales of caravans across the UK skyrocketed with AutoTrader reporting an 18% increase in caravan advert views. Families who would normally holiday abroad were choosing to use their savings to buy a motor home and stay in the UK instead. Dealerships reported rises in prices, particularly in the lower end models where first-time buyers concentrated their searches. However, stock was low before the effects of the national lockdown and so demand is far out-stripping supply, pushing the caravan into one of the most sought-after objects to emerge from the pandemic. Part of the reasoning behind this sharp increase is clearly in the practicality of caravan travel in such uncertain times. They are comparatively low-risk, able to accommodate spontaneous trips, easier than package holidays with the reassurance that comes from owning the space, and after the initial purchase payment relatively low-cost with pitch fees and petrol representing the bulk of the costs.

As well as this, a stronger awareness of the environmental impact of international travel and a greater desire to be closer to nature may also have been considerations that favoured the caravan’s pandemic popularity. The Guy family’s logbook often emphasises the pitches the family stayed in with one poignant entry from June 1950 describing the newly reconstructed Cloth Hall in Ypres where the writer reminisces on his experience of seeing the same building during World War One.

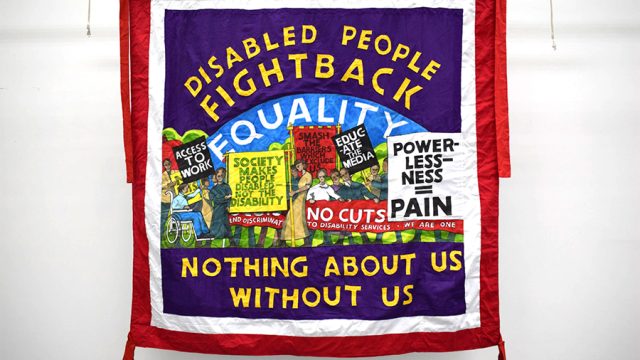

Like many objects highlighted by this project, several social issues coalesce around the caravan. It encapsulates the deepening socio-economic divides in our society such as between those who own caravans as leisure vehicles and those vulnerable groups who used caravans as emergency shelters during lockdown. The growing popularity of caravans is further testament to the ways our priorities have changed and may offer a glimpse into life post Covid-19.

Further Reading:

‘Coronavirus: campsite bookings soar in UK after Spain quarantine’ Josh Hallyday, The Guardian, 27 July 2020.

‘Scottish government ‘furious’ at travellers to Highlands and Islands’, Libby Brooks, The Guardian, 22 March 2020.

‘People and Nature Survey: How are we connecting with nature during the coronavirus pandemic?’, Marian Spain, Natural England Blog, 12 June 2020.

‘Why The Campsite Is The Best Way To Escape The Corona Hysteria’, William Coleman, Caravan Times, 16 March 2020.

Related Objects from the Collection:

From Coventry Transport Museum

1959 Standard Atlas Camper Van (COVRT.2007/143)

From the Victoria and Albert Museum

Toy Caravan, John Heys, Manchester, UK, 1943 (V&A: B.259:1 to 26-2009)