Cash usage halved in the first few days of lockdown. Signs saying ‘No Cash’ or ‘Contactless only’ appeared in the windows of essential shops. Passing hand to hand, purse to pocket and in and out of cash registers, a £20 note makes on average 2,300 transactions in its ten-year lifetime. Gestures once innocuous parts of everyday experience are now risky acts of contagion. The new polymer banknotes and metal coins are both made from materials on which the coronavirus can last for over 72 hours. The pandemic is accelerating the divorcing of touch, place and social interaction from money. In the process many in lockdown Britain have been unable to buy the things they need: they’ve got cash but now live in a cashless society.

My earliest relationship to money was as a physical thing. Holding a penny made your hands smell like blood. A bank note might fall out of a birthday card. Coins appeared under a pillow in exchange for a milktooth. Money also had etiquette. “Look me in the eye when you pay for that”, Sami at the corner shop would say kindly. Contactless payment diverts the physical and social aspects of money. The presence of a small computer on a stand between shopkeeper and shopper drags everyone’s attention to its dull greenish screen. You both wait for the digitised tick of a completed transaction, a textual prompt to remove your card. Your eyes need not make contact. Or you might choose a self-checkout: a true ‘contactless’ exchange.

Contactless technology and the ability to shop online has undoubtedly made lots of people safer and happier during lockdown. But as with many aspects of the pandemic in Britain, this has shifted the burden onto the most vulnerable while enriching the wealthiest. People who earn less than £10,000 a year are 14 times more likely to depend on cash than those earning more than £30,000. Contactless payment was introduced to the UK thirteen years ago, and in February 2020 alone 723 million such transactions were made. Yet 1.2 million British adults are ‘unbanked’. And many of the people who have bank accounts don’t have internet banking and instead rely on ATMs or the Post Office to collect benefits and pensions in cash. Some of those who would rather bank online are prohibited by the expense of internet and mobile data. Others live in rural areas without broadband or mobile signal. Generational and class divides, exacerbated by digital poverty, are creating a bifurcation in currencies in Britain.

Money is an act of faith. Its value is not equal to the materials that constitute it. Instead, communities of individuals have to believe that either a physical object or a virtual signifier represent an agreed worth. We are always transacting in symbols. As such, throughout history cash has created political identities and has been designed to affirm the borders and identity of a nation. Coins from the Byzantine empire, like this one pictured from the V&A’s collection, were distributed to homogenise trade within newly colonised countries. Currency provided economic stability, but was also a reminder at every transaction of who your leaders were. The V&A’s collection contains relics of cash. There are objects for saving, such as pottery moneyboxes that have survived unsmashed. As well as objects of charity such as Kashkuls, the begging bowls of wandering dervishes which were carved from the shells of the coco de mer palm. The slow shift towards a cash-free society can be seen in our material possessions. Now, our wallets, bags and phone cases are designed to accommodate thin pieces of plastic with rounded corners, measuring 85.60 mm × 53.98 mm.

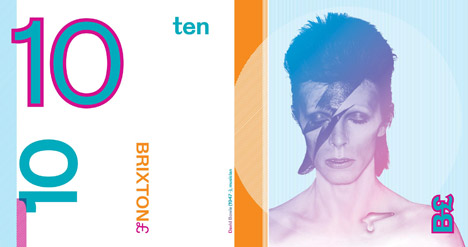

The demise of cash is a social distancing measure that threatens the diversity and independence of our communities. In 2010, the Brixton Pound (B£) harnessed the power of cash to create belonging and identity when it was developed as Britan’s first urban local currency. Supported by a network of independent businesses and shoppers, the B£ reinforces the strong and diverse local economy by helping money ‘stick’ to Brixton. The notes are designed to commemorate famous people from Brixton – such as musician David Bowie and political activist Olive Morris – whose likenesses are combined with imagery lifted from local graffiti and public sculpture. Localised currencies such as the B£ point to one of the benefits of physical cash: it creates social connections and retains value within a community.

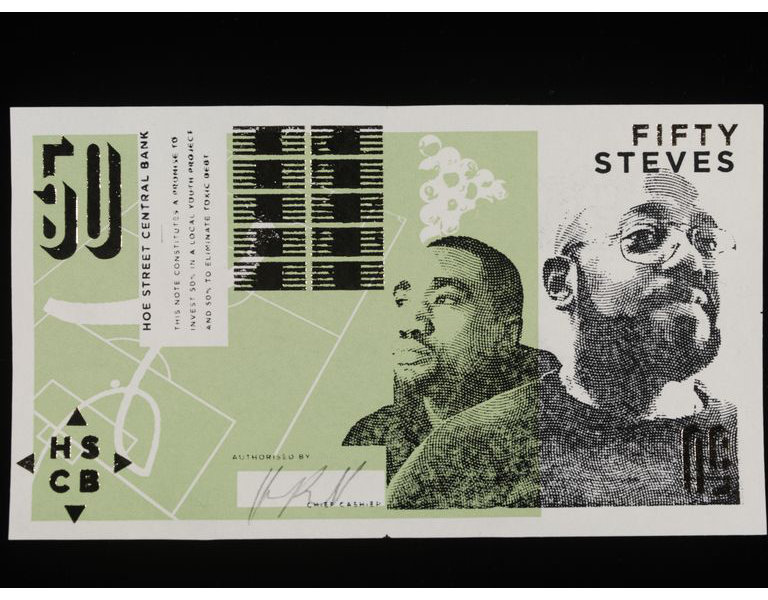

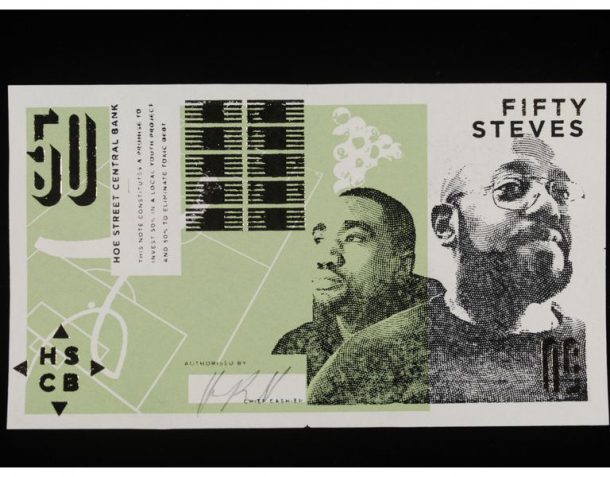

The symbolic value of currency has been powerfully used by activists and artists, seen for example in Walthamstow’s Hoe Street Central Bank (HSCB) which opened in March 2018. Artist Hillary Powell screenprinted bank notes that featured portraits of local community leaders from E17, one of the most deprived boroughs in the country. Through the initiative, HSCB was able to raise £40,000: 50% of which went to the causes represented on the notes, and 50% was used to purchase and write off local debt valued at £1.2million. The bank has re-opened to continue its work during the pandemic. The B£ and HSCB are important templates for how trade and money need to be reimagined for a fairer society, something made all the more urgent by the unfolding financial consequences of this pandemic.

Further Reading:

Access to Cash Review, Access to Cash, March 2019.

‘Coronavirus accelerates shift away from cash’, Daniel Thomas and Nicholas Megaw, The Financial Times, 27 May 2020

‘Should money be washed during the COVID-19 pandemic and will it spread coronavirus?’, Yahoo Finance on YouTube, 26 March 2020.

Related Objects from our Collections:

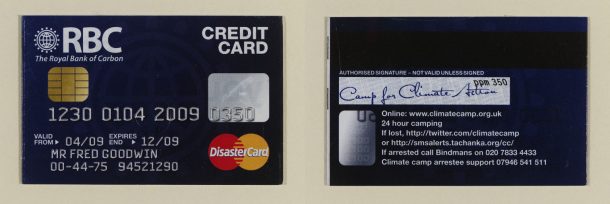

Camp for Climate Action at Heathrow Airport ‘credit card’ leaflet, 2007. (E.612-2014 )

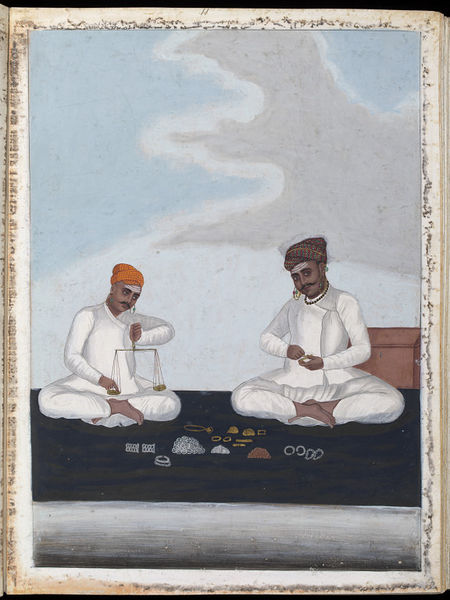

Two shroffs or cash-keepers, ca. 1805. (AL.9254:11)

Pendant by Four Star General, 1988. (T.1031-1994)