Chairs will likely not go down in the history of Covid-19 as much to talk about. Their agency in solving a global pandemic is, of course, minimal. But in their own small way – as is the case with so many objects right now – they are playing an unexpected supportive role. Two weeks ago, as a case in point, I encountered my neighbour returning to his flat with two freshly purchased camping chairs. He had complained that, with the only social outlet available being sitting in parks, his hips and knees couldn’t take the new cross-legged-on-the-ground position that was a prerequisite. And indeed, he’s not alone. Since our encounter, I’ve noticed the number of camping chairs in my local parks consistently rise.

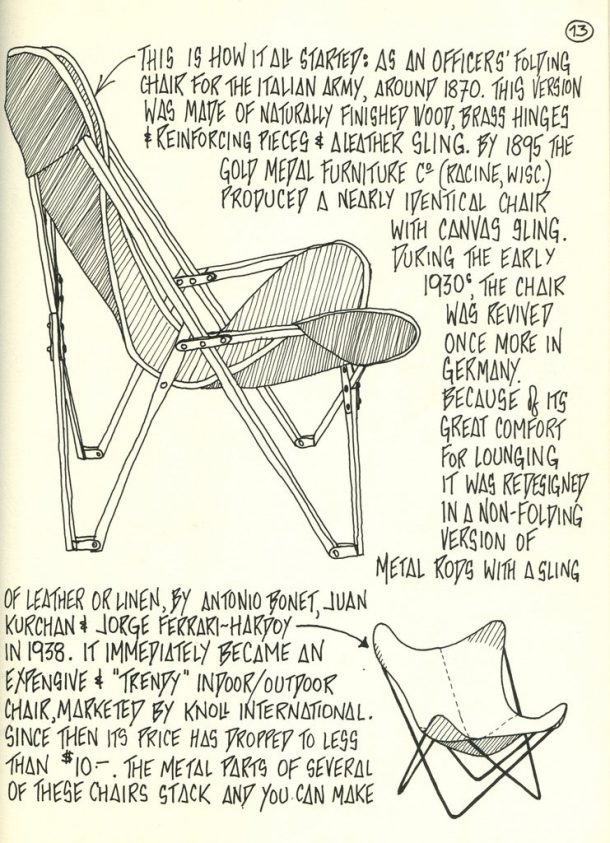

While carrying a chair with you on-the-go might seem novel now, it is steeped in historical practice. Simple folding chairs and stools are some of the oldest designs we know of; evidence of their use dates back to at least the fifteenth century BCE. The chair was purpose-built for the nomadic life of the time, where one’s worldly possessions were fashioned to be able to pick up and go at a moment’s notice. Post-nomadic life, the folding chair has found continued purpose and existence in various military campaigns, exploration missions, and films sets, to name but a few examples.

Paradoxically, while our domestic life has become more sedentary, our interpersonal life – with the opening up of parks and unlimited amount of time allowed outside – has rendered many of us nomads of sorts, trekking to strategically calculated midway points to meet with friends and family. And as we do so, we’re often bringing our furniture and possessions along, unfurling our bounty on the first patch of green we find.

When James Hennessey and Victor Papanek published their influential books Nomadic Furniture (1973) and Nomadic Furniture 2 (1974), they were looking to a world that was increasingly mobile. The average American would move every 2-3 years, they claimed. To emphasize the point, in the preface Papanek and Hennessey sign off with the many different locations in which the book was written (Stockholm, Vienna, Copengagen, Valencia). In reaction to this increased mobility, they proposed a series of cheap do-it-yourself fixes to furnishing your constantly changing abode. Such jet-setting trends seem antithetical to our current ideas about the need for slowing down, reducing air travel, and addressing the climate emergency. Yet remarkably nomadic furniture still persists under lockdown, in a way I doubt Hennessey and Papanek could have foreseen.

Even chairs never meant for the outdoors are seeing the sunshine. Early on, I noticed several attempts at spring cleaning taking place in my neighbourhood. Lacking guests to entertain, and desiring more space inside, households were sacrificing their excess and unused chairs to the curbside for disposal. Others were simply moving their inside chairs to front stoops and gardens, allowing their owners to find some sociability in the public life of the street. The home decor tastes and dis-tastes were being put out on display.

The chair as an agent of sociability has been strongly emphasized during lockdown, but less appreciated is its inverse role in connoting privacy and social distance. A good historical example can be found in the café, which proliferated in European cities throughout the nineteenth-century. Here, mass-produced chairs, such as the enormously successful bentwood varieties from Gebrüder Thonet, were deployed as a way of carefully organizing varying degrees of sociability and privacy while out in public. In contrast to its predecessor, the eighteenth century coffeehouse, where anyone who entered was meant to engage in open dialogue with others, the nineteenth-century café was a place to be alone in public. Cheap, lightweight, moveable chairs were a way of quickly marking spaces out into invisible bubbles of privacy; a shield against the hustle and bustle of the increasingly frenetic metropolis.

So again, we see the chair playing the part of not just conviviality but of keeping people apart. This role of the chair as social distancer has produced some of the most uncanny images during Covid. On 24 April, 1,000 chairs were placed out on an empty Römberberg Square in Frankfurt as a protest by the gastronomy industry for more government support. A similar action took place in Athens on 6 May in front of the Greek Parliament to protest the devastation of the restaurant industry. This notion of a chair as a stand-in for a person wasn’t quite enough for the fans of the German Bundesliga team Borussia Mönchengladbach, who paid to have cardboard-images of themselves occupy the empty stadium seats during the audience-less matches that took place in May.

Elsewhere, industries are looking to more sustainable socially-distanced seating arrangements for when actual people can return. In April, proposals were being sketched by airline industries as to how to rearrange the famously cramped seating of economy class; the unconvincing initial ideas included acrylic shields and a reversed middle seat. In late May, the Berliner Ensemble removed 500 of its 700 seats in its auditorium to create a new socially-distanced scheme for live performances, revealing a strange and haunting fragmented layout.

It’s a tricky balancing-act; get the spacing wrong and it feels more like an act of coercion towards a public whose trust needs to be won. In May, for example, the White House began regularly holding press conferences outside in the Rose Garden, with journalists generally spaced out to preserve social distancing. But by 5 June, journalists were outraged to discover chairs had been deliberately moved closer together, forcing them into closer proximity with each other, simply because staffers had deemed that it ‘looks better’.

Despite the great effort, all of these seating responses feel somehow unsatisfying. The image, either of an empty chair or a sea of empty chairs, produces a strange psychological effect. It’s an invitation which can’t be taken up to join again in the crowds of the city; to be together with strangers; a measure of civitas beyond our familial circles. The chair, as it turns out, is a potent metaphor for city life, which may still take a long time to get back to.

Related Objects from the Collection:

X-Frame Armchair, Italy, 16th century (7196-1860)

Text from Search the Collections: ‘X-frame’ chairs were originally folding campaign stools, used by Roman Generals. They were adopted by emperors and potentates, although, by 1550, they had become less symbolic of power and authority than they had been in earlier centuries. This example dates from about 1550, and would probably have been placed in a hall or chamber of a grand house. It formerly belonged to Jules Soulages of Toulouse (1812-1856), very much a pioneer in collecting decorative arts of the Renaissance. This type of chair was much copied from about 1880, when such tastes had become more fashionable, and most surviving examples date from about then.

Folding Chair, China, 1700-80 (FE.1-1971)

Text from Search the Collections: This folding chair decorated with painted peonies, scrolling foliage and dragons among clouds and waves on a red ground retains its solemnity and grandeur. Although folding chairs of this sort were used by the Emperor when receiving guests on formal occasions, they were also an article of convenience. Their portability made them suitable for use in the garden, or in reception rooms when there was a sudden influx of honoured, but unexpected, guests.

I shall look at chairs with fresh eyes, thank you