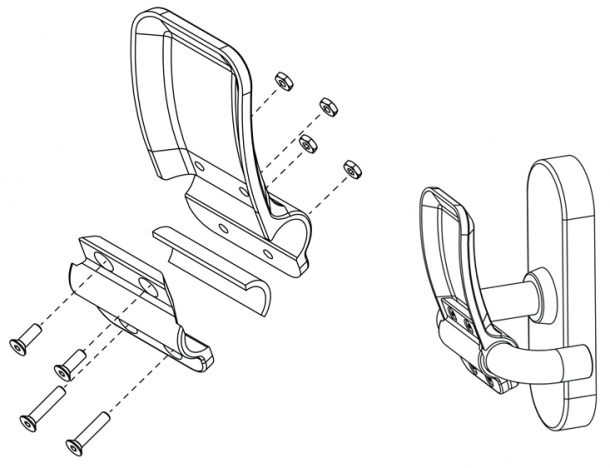

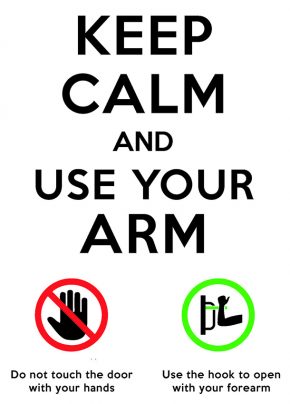

On 17 March 2020, a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine revealed that coronavirus can stay on surfaces such as plastic and stainless steel for up to 72 hours. Suddenly some of our most commonly-used objects, none more than the door handle, became the potential breeding ground for deadly germs. 3D printing company Materialise quickly formed a response in the form of a suite of 3D printed door handles that would slot over the top of your existing ones, accompanied by the catchy slogan ‘Do no harm, use your arm!’. Clearly they had the whole team on board.

According to Business Insider, it took the team 24 hours to create, test and validate the door handle before they were able to upload the open-source free designs. If you don’t have the ability to print at home, you can order a set for yourself. A pair cost between £26 and £52, depending on the size, as, somewhat fairly, the price is entirely driven by the costly 3D printing process, and no other profit is added.

These designs aim to reduce harm by stopping you from touching the surface of a door; instead, you use your forearm to pull the door towards you, or down to force the lever. Another similar, and perhaps cheaper, response from architectural designers and Bartlett graduates Ivo Tedbury and Freddie Hong is much more DIY, and doesn’t need screws, instead a pair of cable ties hold it together.

Such designs serve a secondary use that could exist long after the coronavirus crisis has hopefully subsided, as a means to open doors that have previously been difficult for many. Form, as we know, should always follow function, but with apologies to the old design gods of yore, it’s not so simple when the function itself is still limiting, or exclusionary, because it didn’t think of those who might not have full dexterity or grip, or might not have the full use, or absence of a limb or hand. It suddenly makes your average lever handle – a seemingly ‘universal’ design – an uninviting way to enter someone’s home.

Those with specific needs have been asking for design to acknowledge this problem of universality for a long time, and now that we all need to find new and novel ways to avoid using our hands, perhaps this could be an opportunity to invite conversations of adaptation and access for all well beyond how we are experiencing life currently. Therefore, the design by Materialise, and that by Ivo Tedbury and Freddie Hong could be considerations (we should refuse to use the word solution here because that demands that being disabled is something to be solved – spoiler, it’s not) for a renewed outlook on the assumptions we make about our most everyday affordances. Materialise offer a number of different adaptations to the many kinds of door handles you might see in life, in your office or home, hospital, or other shared areas, in order to account for the many ways in which we might need to access space hands-free.

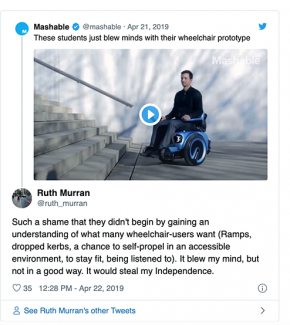

This ultimately indicates towards a problem that design and architecture needs to confront of the problems of infrastructure rather than any one person becoming made better, or fixed – a key thought central to disability theory in context to design. There’s a need for more ramps, not endless prototypes of standing wheelchairs by well-meaning, often able-bodied product and industrial design students. Well-meaning but short-sighted design are what disabled designer Liz Jackson calls ‘Disability Dongles’ in a tweet posted 26 March 2019: “A well-intended elegant, yet useless solution to a problem we never knew we had. Disability Dongles are most often conceived of and created in design schools and at IDEO.”

As previously mentioned, there’s obviously an argument against the universal too, as standards of ergonomics often end up prioritising certain bodies over others in an attempt to cover everybody with the idea of the ‘one true body’. Le Corbusier, in attempting to create what he called “a range of harmonious measurements to suit the human scale, universally applicable to architecture and to mechanical things” produced the arguably hostile Modulor Man, a set of universalist proportions that bodies should expect to be in order for architecture to be at its most successful. Which is where the ability to change, and adapt, with the dissemination of 3D designs, is the key point with this design. With the right know-how, and a little time, a handle can be extended without starting from scratch, or made bigger, wider or smaller to fit a specific person, or printed in whatever colour your heart desires. There have been a number of ‘clean keys’ advertised which can be used by individuals to open doors by attaching it to your keychain, and also allows you to press buttons and other things which require a person to touch something, but these are largely individualistic. The add-on from Materialise, or any add-on at all creates an affordance at an infrastructural, and communal level, where anyone can access it. This feels altogether kinder, which is perhaps what we need right now.

Maybe the 3D printed door handle is the promise of 3D printing finally paying off and moving beyond novelty, however there’s still the issues of skills, time, and money. 3D printing is still prohibitively expensive for some, difficult to get right and do properly. As mentioned earlier, It requires a knowledge of plastics, and also knowing that they aren’t always the most sanitary – the ridges that form during the printing process (especially for cheaper printers) mean that it’s vulnerable to bacteria. However, the design of the handle is that you don’t come into contact with it, your clothes do, so it’s better than nothing at all.

At any point, any of us may experience a change in circumstance, and it’s important to understand the role adaptation plays for us all. The engineer and artist Sara Hendren, who runs the Adapt and Ability lab at Olin considers the many ways in which design should respond to the way we live together now, and into the future:

“The way cultures define, think about, and treat those who currently have marked disabilities is how all its future citizens may well be perceived once their able-bodied become less abled than they are now: by age, degeneration, or some sudden — or gradual — change in physical or mental capacities”.

There’s a hope that this design will lead to a significant transformation in design that takes into account an infrastructure that prioritises health, care and good standards of living, and understands where industrial design and architecture can play a part in enabling an infrastructure of harm reduction across a broad range of people. By listening to and centering disabled people first, in many respects, it benefits all of us, and by taking into consideration the ways in which disabled people already adapt to changing circumstances, able-bodied designers can learn how design needs to be better for everyone. As Liz Jackson says, disabled people are the original lifehackers.

This article was originally written on 20 April 2020

Further reading

- A community response to a #DisabilityDongle, Liz Jackson, Medium, 22 April 2019

- “Human, All Too Human”: a Critique on the Modulor, Federica Buzzi, Failed Architecture, 25 May 2017

Related objects from the collections

Door Handle from Somerset House, designed by Sir William Chambers

The handle and escutcheon are made of cast brass, which has been chased and gilt. A coat of lacquer was then applied to improve its golden colour. Door furniture was considered to be an important element in the decoration of a room in the 18th century. Robert and James Adam illustrate what are described as ‘Designs of Furniture for the locks of doors’ in their Works in Architecture, and the owner of the Soho Manufactory in Birmingham, Matthew Boulton, is known to have supplied gilt-brass door furniture based on Adam designs. This handle and escutcheon were removed from Somerset House when the house was being altered in the mid-19th century.

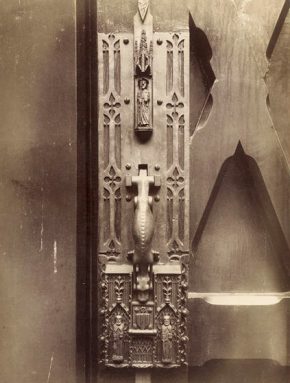

Photograph, Door Knocker, Hotel de Cluny, Paris, France, by Jean-Eugène-Auguste Atget

This photograph is part of a larger project by Jean-Eugène-Auguste Atget to record ‘Old Paris’ which began around 1897 and continued until the 1920s. In it, Atget was driven by the disappearance of buildings as schemes of modernisation swept the city. Ignoring the grand new vistas, he set out to record the character and details of the timeworn streets. He made a stock of prints for sale to artists, museums and libraries, in France and abroad, selling some 600 prints directly to the V&A.