The social media app TikTok has experienced a remarkable boom during the pandemic. Capitalising on the boredom, creativity and savviness of its primarily young audience – 7 out of 10 users are under 25 – TikTok now boasts over 800 million active users and its owner, ByteDance, is worth over $100bn.

Its premise – the sharing of short music and lip-sync videos of under 15 seconds – has thrived during lockdown due to its playful, performative concept and its strict time limit. It’s no coincidence that when our attention spans have shortened but our leisure time has increased, an app that packages succinct, constantly-changing content has thrived.

TikTok’s ‘staccato, no-explanations, absurdist flavour’, as Tom Lamont has described it in The Guardian, has been defined by its proliferation of viral dances, created and coined by users using remixed songs and then copied worldwide. Dances such as the ‘Say So’, ‘Cannibal’, ‘Renegade’, ‘Supalonely’, ‘Savage’ and ‘Attention’ often catapult the TikTok choreographer and musical artist to new (or further) fame.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vo5KgRzbXEI

The commercial success of TikTok reached its apex earlier this year when rapper Drake capitalised on the trend, asking TikTok celebrities Toosie, Hiii Key and Ayo & Teo to create a dance to accompany his new single. The song, ‘Toosie Slide’, has since sparked over 4 million videos and 6.8 billion views on TikTok as of June 2020. The music video, which sees a masked Drake perform the dance throughout the numerous rooms of his empty Toronto mansion, was lauded by Vanity Fair for its zeitgeisty ‘quarantine-core aesthetic’.

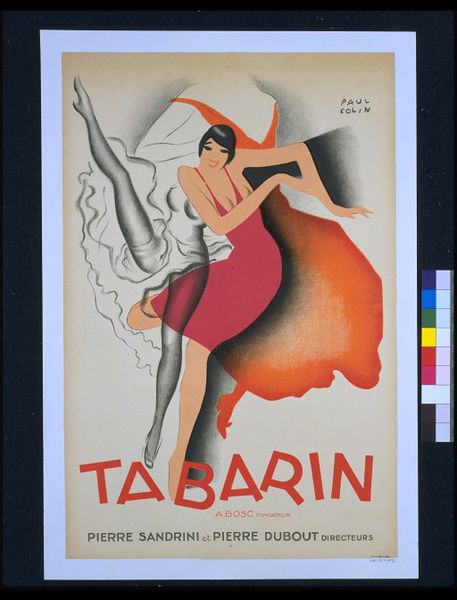

TikTok’s viral dance sensations may seem superficial, but the novelty dance has a rich history, one that may have even inspired the concept of viral entertainment itself. Jason King, an associate professor at New York University, has compared the phenomenon of the 21st century viral dance with the spread of the Charleston a century ago: “To me, [it’s] the same as the black bottom [a dance step that overtook the Charleston in popularity but was based on the same rhythm] in the 1920s. That was one of the ways that the blues became popular – through that dance. It’s the same tradition, but it’s just become so accelerated in the age of the internet. It’s become a structure: a way to do this on a consistent basis. It’s interesting that this concept of virality is something that novelty dances actually prefigured: The Charleston, in a way, was viral.”

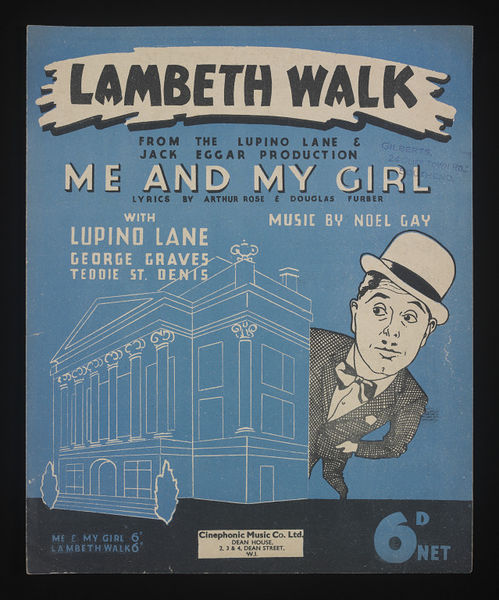

It could also be argued that the dances of TikTok have provided vital comfort and solidarity in a time of crisis – not unlike the dances popularised in the 1920s and 1930s. In 1937, for instance, the musical Me and My Girl premiered at the Victoria Palace Theatre in London, featuring the song ‘Lambeth Walk’ composed by Noel Gay. The number, featuring an exaggerated Cockney dance performed by Lupino Lane, spun off into its own dance craze. Its simplicity (in contrast to the laws of formal British dances) and its ‘Cockney roots’ appealed to all ages and classes across the country. : “The ‘Lambeth Walk’ has not only been the dance success of the year—it promises to continue indefinitely as one of our national dances. It is more than a craze, because it expresses the London spirit, and this Christmas it will be danced in homes all over Britain.”

While marketed as a British novelty dance to rival fads that had travelled over from America, the ‘Lambeth Walk’ took on a new significance as Britain entered the Second World War. Much of the population continued to attend dance halls even under threat of bombing, including ‘Gas Mask Balls’ which encouraged attendees to bring face coverings in the event of attack. The performance of the ‘Lambeth Walk’, a specifically British craze unifying dancers across the country, demonstrated people’s resilience and positivity in the face of uncertainty.

With fascism creeping across Europe, one reporter from The Dancing Times writing in 1939, saw the dance in political terms: “No longer can we treat these dances as frivolities. They have become important, they are international, and truly democratic.”

Perhaps its most enduring legacy is a striking piece of wartime propaganda which capitalised on the nationalist themes of the song. In 1941, the UK Government, edited footage of the German 1934 film ‘Triumph of the Will’ to the ‘Lambeth Walk’ song, making it appear that Adolf Hitler and Nazi soldiers were ‘performing’ the dance on screen. The film was packaged in news reels across the country. The sophistication and humour of the film eerily chimes with TikTok and the meme culture of the internet age.

Further reading:

‘Drake’s “Toosie Slide” Video and the Emerging Rules of Quarantine-Core’, Dan Adler, Vanity Fair, 3 April 2020.

‘‘It’s hard to put the brakes on it. We doubled down’: Charli D’Amelio and the first family of TikTok’, Tom Lamont, The Guardian, 6 June 2020.

‘TikTok Is (Apparently) the Future’, eMarketer, 9 June 2020.

‘Discover the novelty dance move’s long road to legitimacy’, Al Horner, Red Bull, 2 July 2019.

Allison Abra, ‘Dancing in the English style: Consumption, Americanisation and national identity in Britain, 1918–50’ Studies in Popular Culture (Manchester University Press, 2017)