What time is it? Over the course of the lockdown, time has felt unsettlingly warped. I’ve found myself increasingly losing track of the time as the minutes, hours, days and months blur. Since the coronavirus pandemic started there has been a slew of articles and research suggesting far from being alone, many people have experienced a shift in their sense of time.

We often think of time as a noun. We associate it with scarcity and value it as a precious commodity. We’re encouraged to save it, reminded that time is short and advised to use it wisely and productively – ‘time is money’ goes the adage. And with the spectre of the pandemic, we are even more acutely aware of the limited time in the human life span.

Time feels real, it can be thought of as linear and inexorably moving forward. It has flow. Roman emperor-philosopher Marcus Aurelius described time as a river of passing events. It has direction and order, it’s the succession from the past, through the present, into the future. Time also has duration and can be quantified as the period between events. Time, however, is not always what it seems and there are many alternative ways of thinking about it from Einstein’s theory of relativity where time constitutes a fourth dimension to theoretical physicist Carlo Rovelli’s argument that time is an illusion.

The more I think about time the more perplexing it seems. What the global coronavirus pandemic has heightened for me is an awareness that time is subjective. Just as many people have had the sensation that time has sped up as those who have felt it has slowed down. Multiple factors colour how we perceive time. Claudia Hammond, author of Time Warped: Unlocking the Mysteries of Time Perception, succinctly sums this up in observing:

“The experience of time is actively created by our minds. Various factors are crucial to this construction of the perception of time – memory, concentration, emotion and the sense we have that time is somehow located in space. Our time perception roots us in our mental reality. Time is not only at the heart of the way we organise life, but the way we experience it.”

A survey by Liverpool John Moores University suggests that social and physical distancing measures put in place during the Covid-19 pandemic significantly impacted people’s perception of how quickly time passed compared to their pre-lockdown perceptions. The survey revealed that the distortion of time and the feeling of lockdown passing more slowly than normal was associated with older age and reduced satisfaction with social interactions.

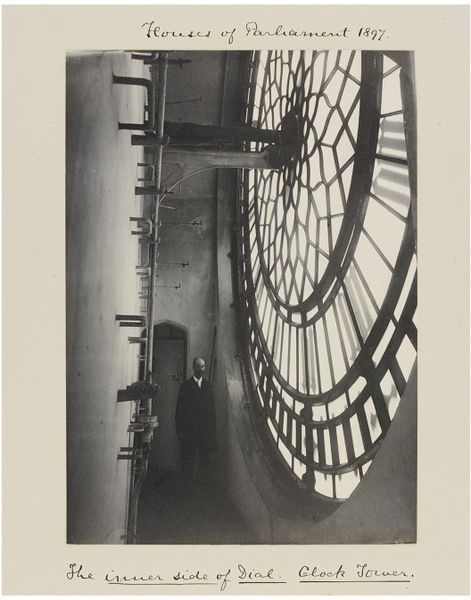

To fight the subjectivity of perception, the world is replete with objects that mark out time more systematically. From sun dials to analogue and digital watches, and apps on phones and laptop screens – when it comes to instruments to tell the time with, we’re spoilt for choice. My personal favourite are clocks. They are both functional and decorative. As a child I was fascinated by their motion and sound. The mantel piece in my flat is a small testament to this love affair.

Clocks have fundamentally changed our world. Whilst water clocks, sundials and hours glasses existed in the ancient world, they had a very different impact compared to the way clocks today shape the organisation of our lives. Rovelli notes, “It is only in the 14th century in Europe that people’s lives start to be regulated by mechanical clocks. Cities and villages build their churches, and place a clock on the belltower to mark the rhythm of collective activities. The era of clock-regulated time begins.”

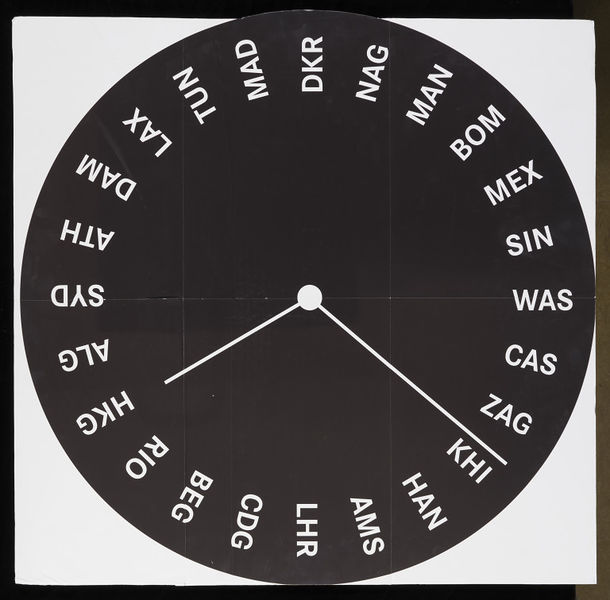

The V&A is home to all sorts of clocks including longcase (also known affectionately as grandfather clocks), bracket, table, desk, wall, alarm, carriage, cabinet, teaching, lantern and astronomical clocks. ‘10 of our Favourite Clocks’ is a gloriously illustrated blog post highlighting the different clock design styles in the collection including rococo, art deco, post war design and the Arts and Crafts movement. During this time when we are encouraged to work from home, the clock I miss the most is ‘Frozen Sky’, made by the artists Ben Langlands & Nikki Bell. Its dials are composed of the three-letter codes used to represent international airports. It was designed to represent urban centres in an abstract constellation and evoke the transience of contemporary urban life. I used to pass this clock daily as it is hung in the Prints and Drawings Study Room.

I still take great pleasure in looking at clocks but for me these days they are now synonymous with time distortion. When there is uncertainty, time feels elastic. One of the biggest uncertainties is not knowing when the pandemic will end.

Further Reading:

What We Get Wrong about Time, Claudia Hammond, BBC Future, 3 December 2019.

Distorted passage of time during the COVID-19 lockdown, Ruth S. Ogden, Science Daily, 9 July 2020.

There Are No Hours or Days in Coronatime, Arielle Pardes, Wired, 5 August 2020.

Time is elastic’: an extract from Carlo Rovelli’s The Order of Time, Carlo Rovelli, The Guardian, 14 April 2018