The window is an element of domestic architecture designed to go unnoticed. Like other things we see every day, windows become invisible through familiarity, as much as through transparency. Over the course of the pandemic, many of us have become intimately reacquainted with the limits of our household space: the size of our living room, the strength of the WiFi, the movement of light across the floor over the course of the day. Windows occupy the edges of the home, but are also a crucial portal beyond it. My flat doesn’t have a balcony or garden, so in the first surreal weeks of lockdown I felt renewed gratitude for my windows, for fresh air and natural light.

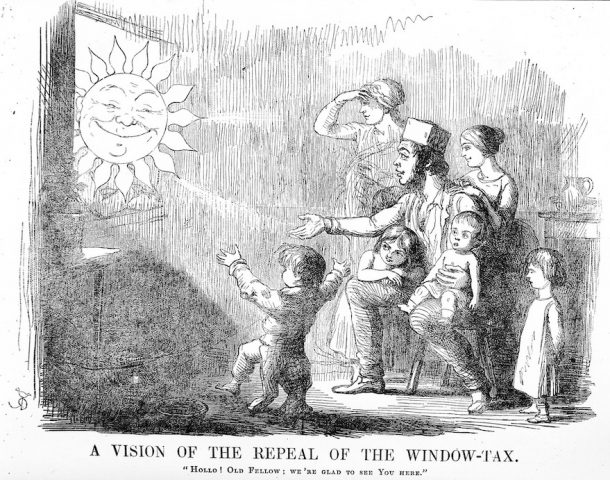

The relationship between windows and good health has long been understood. A window tax was introduced in England in 1696: houses with more than ten windows were charged for every additional one. It was intended to fall upon the wealthy, who were more likely to live in lavish homes, but it impacted the urban poor, many of whom lived in large tenement buildings. Regardless of how these had been subdivided for tenants, they were considered single structures and taxed heavily. Landlords bricked up windows to avoid the payments—a legacy still visible on façades today. From the early eighteenth century, the negative impact of the tax on public health was being decried in pamphlets and popular songs, as those in homes without proper light and ventilation suffered disproportionately from disease. In the battle against Covid-19, the German government have encouraged the all-seasons practice of Lüften—regularly opening windows to let fresh air circulate through a building—arguing for it as a cheap and effective way of limiting the spread of coronavirus.

Thanks to a popular campaign, the window tax was scrapped in 1851, and its repeal coincided with the popularisation of the window box. Window boxes made of terracotta or metal took off in the Victorian period in England, and were used to grow vegetables, herbs, and flowers, just as we do today. As Spring arrived during lockdown, demand for window boxes surged, along with seeds and gardening tools, as the pandemic reinvigorated the joy and independence of doing things by hand. The window was embraced as an active extension of indoor space, modest access to nature, and a zone where the private space of the home meets the public space of the street. People pinned rainbow paintings and messages of support for the NHS in their windows, and leaned over their sills on Thursday evenings to applaud key workers. The window became an active site for the public expression of solidarity and community.

In Beirut, Lebanon, windows entered into public consciousness this summer for a different reason. On 4 August 2020, 2,750 tonnes of ammonium nitrate exploded at the Port of Beirut, where they had been stored for several years. The explosion killed 203 people, injured thousands and left many homeless. A chilling reflection of the Lebanese government’s criminal negligence and corruption, the blast’s effects were compounded by pre-existing crises: economic collapse, hyperinflation, poverty and pandemic. One immediate material effect of the explosion was the shattering of glass. Almost every window in Beirut was blown out of its frame; the reach of the shockwaves was measurable by broken panes in villages miles from the capital. In the hours and days that followed, the grating sound of glass being swept from balconies and into the curb roared across the city. Months on, glass still crunches underfoot like shards of ice, lurks in the corners of people’s homes, and waits in vast mounds for collection, recycling, disposal. Many windows are still covered with tarp or wood—demand for glass has soared and supply is overwhelmed.

Windows are both mundane and powerful things, thresholds and portals. We take them for granted until they are gone, and it is hard to live safely without them. I think of all the glass from all the windows in Beirut’s diverse architecture—Ottoman mansions, 1970s apartments, Starchitect-designed high-rises, the iconic stained glass of the Sursock Museum—all now half-returned to dust, and am glad for the quiet, familiar presence of my own.

Rachel Dedman is the Jameel Curator of Contemporary Art from the Middle East, V&A. From 2013-2019 she lived and worked in Beirut, Lebanon.

Further Reading:

‘From window to jug: Lebanese recycle glass from Beirut blast’, Sharjah24, 7 September 2020.

Related Objects from the Collection:

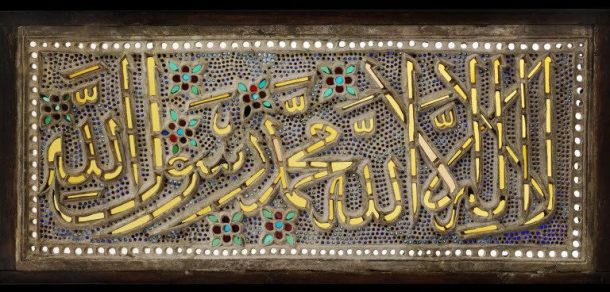

Glass Window, 1st—3rd century, Wilfred Buckley collection (V&A: C.123-1936)

Window of carved stucco and coloured glass, Egypt or Syria, before 1883 (V&A: 1202-1883)

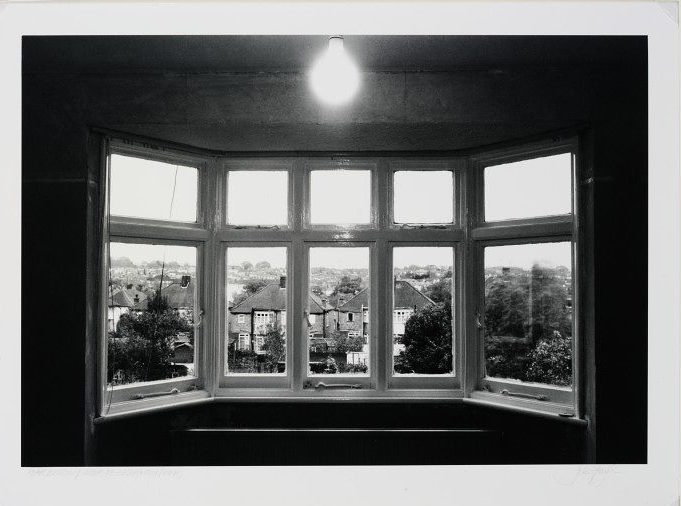

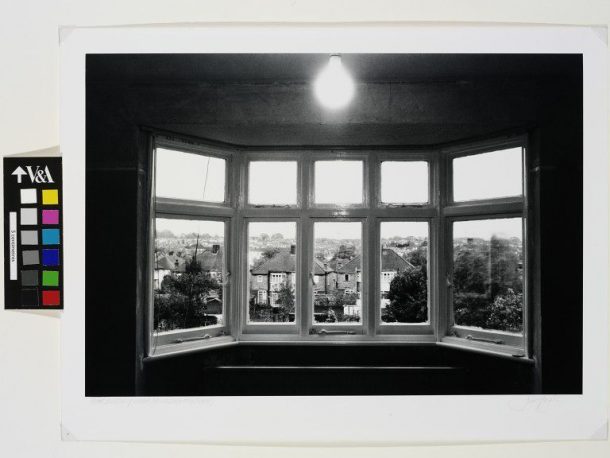

From Search the Collection: “This image is from the series ‘Ideal Home’, which records successive changes in the decor of a north London home throughout the 1980s. The view through the window is probably a mirror image of the other side of the street: 1930s semi-detached houses – the epitome of British suburbia. Through delving into the detail of domestic arrangements, Taylor catalogues the ordinary suburban lifestyle, analysing people’s connection to commodities and their environment.”

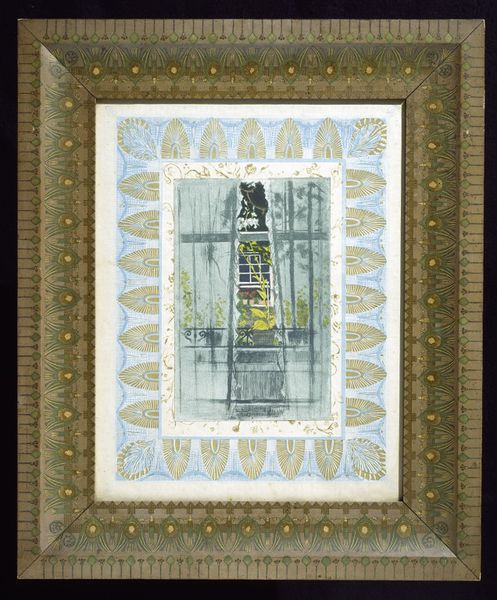

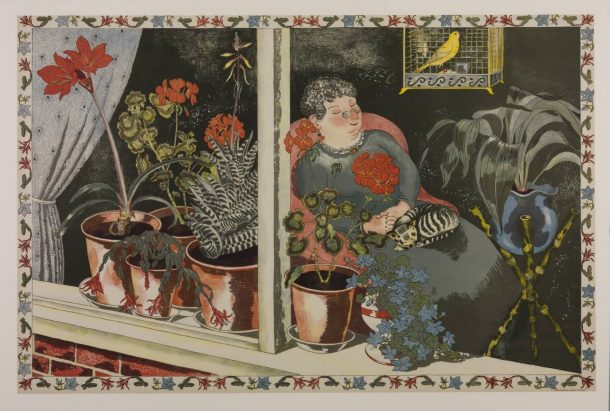

‘Window Plants’ (colour lithograph on paper), John Nash, 1945 (V&A: E.5157-1958)

‘A Window Seen Through a Window’ (etching), Theodore Roussel, 1897. (V&A:E.1479-1991)