by Katy O’Neill and Francesca Butcher

‘Menswear is about subtlety. It’s about good style and good taste.’

Alexander McQueen

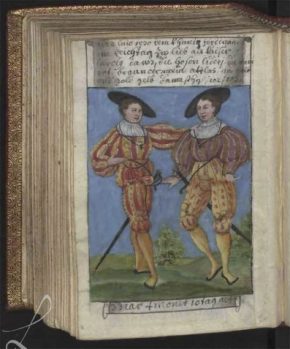

A first impression of the garish red and yellow outfit depicted [above] would seem to contradict McQueen’s call for subtlety. Yet, as Professor Ulinka Rublack explained in a recent seminar in the V&A/RCA History of Design Research Seminar series, it can be seen as an exceptional example of early modern ‘good taste’. In detailing the context of the ensemble, made in 1530, she revealed the potential of the illustration to provide new insights into the construction of conceptions of ‘taste’ and ‘style’, involving the interplay of new fashions, individuality, and the politics of status, religion, and urban consumerism.

Her research for the upcoming work ‘The First Book of Fashion’ focuses on the source of the image: the ‘Klaidungsbüchlein’ of Matthäus Schwarz (1497-1574), an accountant employed by the famous Fugger family. The ‘Little Book of Clothes’, as the German term translates, is regarded as a unique document in the history of fashion, containing 137 watercolour images of the experimental styles Schwarz wore throughout his lifetime.

The book is a unique, beautiful and honest portrayal of a man’s fascination with fashion in the sixteenth century. Alongside the images Schwarz provides a small commentary of his outfits, and his own figure, through a period of time. His nude portrait is a rare example of a secular nude, comparable to those of Dürer, and his comments on his aging and portly body show how sincere this book is, and why it inspired Rublack to recreate one of the most interesting outfits Schwarz chose to display.

The yellow and red outfit was made to please Charles V for the Imperial Diet of 1530 and to show off Schwarz’s enviable style credentials. Due to the rising tensions over Protestantism, it was important for guests of the Diet to show allegiance to Catholicism and the Empire. Thus, the colours of clothing were heavily weighted and were used to portray such loyalties. The choice of yellow for Schwarz was not only a fashionable choice but a political one too. The outfit Schwarz saw fit for the occasion consisted of a doublet made of panes of red and yellow silk over a billowing linen shirt to keep the voluminous shape. To complete his look Schwarz wore yellow leather hose, slim shoes and a black beret, accessorised with a sword and red purse.

Having deepened our understanding of the context in which such attire was worn, Rublack moved on to discuss part of her research that added a physical depth to present interpretations of now-absent objects. As shown by the video from which the next image is taken, she collaborated with theatre designer Jenny Tiramani to create a historically accurate reconstruction of the red and yellow outfit.

Alongside the re-enactment of past events, the reconstruction of past things was long marginalised in the world of ‘serious’ academic history. In the words of Vanessa Agnew, it was seen as a ‘cultural phenomenon’, belonging to the likes of ‘nostalgia’ toys, living history museums and television programmes.

In recent years, historians asking questions of how people experienced their environment have somewhat caught up with archaeologists, curators, and conservators in appreciating the benefits of reconstruction. Historians of science, such as Peter Heering, were amongst those who first strayed from the solely textual path, re-testing experiments and instruments. The object-focus of historians of material culture has similarly led to practical investigations of process, as seen in the work of Pamela H. Smith on artisanal knowledge in the sixteenth century.

The reconstruction of Matthaüs Schwarz’s clothes suggests that this experiential method can be as useful for historians of textiles and fashion. The challenges inherent in assembling the outfit, made from materials that would have been used at the time, simultaneously provided an advantage: an appreciation of the time (and expense!) it would have taken for Schwarz to source appropriate fabrics, ascertain the quantities needed, and experiment with shape and colour. Perhaps most importantly, the production process demonstrated the significance of trained craftspeople, whose skills were often handed down verbally. Jenny Tiramani’s expertise in historical materials, cuts, and construction, gained through years of experience, was clearly invaluable to the project.

Crafting the apparel lent Rublack and Tiramani a rare insight into the perspective of an early modern consumer. However, just as the dishes created by food historian Ivan Day can be said to be just as valuable in the eating as they are in the cooking, the value of the reconstructed clothing lies in the wearing as well as in the making. Unlike artifacts that survive from the period, which require extensive conservation and care, these remade pieces allow us to get a sense of that most elusive stage in the life-cycle of an object: use.

For the viewer, seeing the dramatic, bright colours of the doublet and hose ‘as new’ recaptures a sensory experience. Compared to viewing surviving fragments, the visual impact of the whole ensemble brings the present-day viewer even closer to contemporary experience. As part of the outfit, on a body, the individual pieces of clothing are in their material context. This can provide explanations for otherwise misleading or confusing aspects of an object, as Karin Dannehl suggests for the wide skirts and bare feet of female kitchen assistants. To the modern viewer, both seem a health and safety hazard. Yet the women who replicated this context when re-enacting early modern cooking in a period property suggested that the skirts actually protected them from flames, whilst their bare feet on the flagstones warned them the closer they came to the fire.

As Ulinka Rublack’s seminar demonstrated, the historian’s task of ‘reconstructing’ the past in order to understand it does not always have to be conducted via the medium of text. Nevertheless, her upcoming work promises to be a fascinating read, blending the themes of fashion, politics, colour, and identity.

‘The First Book of Fashion’ tumblr – a collaboration between Rublack, photographer Maisie Broadhead, and fashion designer Bella Newell, imagining Schwarz’s project in a modern context – is also worth a look, and can be accessed here.

Thanks for the article.