Dedicated to the memory of Erin Gilmer, a beloved member of the chronic illness community on Twitter, who died following a long struggle with untreated chronic pain. Erin was an attorney and patient advocate who fought for disability- and trauma-informed healthcare. Erin did not survive, but she will not disappear.

This piece contains triggering and/or sensitive material about suicide and self-harm.

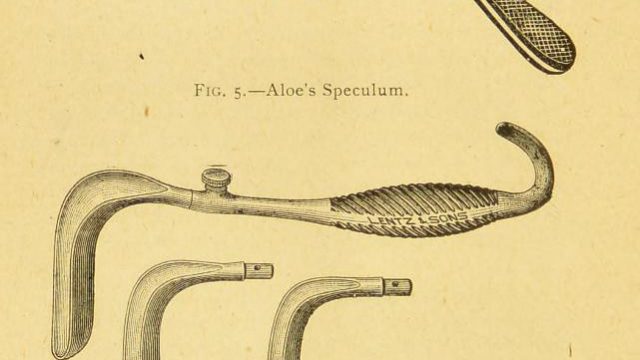

The GynePunk 3D-printed speculum is an undeniably perplexing artefact. It is a clinical tool translated into digital form, making it available for non-clinicians to customise, distribute and fabricate. This translation also renders the tool materially unusable. The manufacturing processes available to support its re-translation to physical objecthood rely on materials that are too brittle, porous or finely ridged to allow for safe internal use.

A critic could be forgiven for asking, ‘What does this accomplish?’ Like so much other work that seeks to effect social change through the digital milieu, the GynePunk 3D-printed speculum can easily be read as a kind of ‘armchair activism’ – something that positions itself as radical while doing little to effect meaningful, material change. I would argue, however, that such critiques tend to neglect the ways digital activism operates within disabled and especially chronically ill communities. The GynePunk speculum calls attention to the desperate need for tools and methods for bypassing the clinic and the problems of safety that foreclose access to them.

The role of the patient evolved alongside the early clinic. Both were shaped by post-feudal class conflict and an increasing emphasis on classification within practices of early modern science. In his 1976 paper ‘The Disappearance of the Sick-Man from Medical Cosmology, 1770–1870’, sociologist Nicholas Jewson argues that the relationship between sick people and doctors changed substantially as medical practice became organised around hospitals. These institutions brought together large populations of sick and destitute people who had little power to control what was happening to them. They also brought together groups of professional medical practitioners who gained power by working together in newly collegial communities. According to Jewson, interactions between the clinicians and the hospitalised sick were characterised by ‘strictly prescribed patterns of deference’. The sick-person became the patient, a passive role whose function is ‘to endure and to wait’.

During the same period, early pathologists were reshaping the meaning of sickness. Influenced by natural scientists who described and mapped elements of the external world in an effort to discover the relationships between them and the rules that governed them, pathologists described and mapped elements of the human body. Through their work, sickness came to be understood as having a specific, concrete, observable location in the body. Symptoms had no more inherent meaning; they could only point to pathological lesions that could be revealed upon autopsy (or, much later, upon radiological imaging, blood testing or biopsy). The doctor’s pursuit was no longer to heal the sick-person but to remove the pathology from their body. And bodies do not demand accountability or compassion.

I began researching and administering my own medical treatments in 2018. I had been sick for 26 years and had lost the ability to do paid work 2 years earlier. I had moved into my parents’ house in rural Ontario, where I slept up to 16 hours a day. When I slept, I dreamed about things I needed to do in the waking world, but no matter how hard I tried to reach them, I couldn’t. When I awoke, all I could feel was the pull of sleep, like a fifth fundamental force ripping my consciousness apart at the seams. I was actively suicidal.

The cardiologist who diagnosed me with Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome apologised that he could not offer me any treatment to manage it, but he did offer me an in-patient stay in the psychiatric ward after noticing the cuts on my arm. A sleep specialist told me he couldn’t do anything more for me and suggested I learn to accept my body’s sleep needs, noting that this was how people dealt with such things decades ago. An allergist scoffed when I asked whether my narcolepsy might be a result of my newly diagnosed mast cell disorder, since one of the primary chemicals released by mast cells plays a role in regulating the sleep-wake cycle. Eventually, I realised that if someone were going to save my life, it would have to be me.

I turned to Wikipedia, Google Scholar and chronic illness spaces on social media to trace the biochemical underpinnings of my symptoms. I identified prescription medications that would target the right pathways, then searched for analogues in over-the-counter and plant medicines. I was successful; I began sleeping seven hours a night. My Epworth Sleepiness Scale score decreased from 23 to 2. I regained my driver’s license and the ability to participate in a world that exists outside my brain.

The allergist told me I was welcome to return to his clinic when I abandoned my ‘naturopathic’ beliefs. A pharmacist phoned my general practitioner to inform her of my risky behaviour after I inquired about possible interactions between one of my plant medicines and the few prescription drugs I was taking. My haematologist told me she could not condone the use of ‘supplements’ and warned of patients who had tried such things only to return to the hospital with liver or bone marrow failure. I asked each of them to offer me alternatives. Each of them simply repeated that self-treatment is dangerous.

Sick-people whose illnesses cannot readily be mapped to tangible pathologies threaten the authority of clinical ways of knowing. Thus, the clinic dismisses them. When those sick-people seek to treat themselves, the spectre of danger is invoked against them.

I interpret the GynePunk 3D speculum as an artefact of what it means to be a sick-person failed by the clinic in the twenty-first century. When you are denied the care you need to survive, you turn to digital channels to seek tools and methods that will allow you to bypass the systems that have denied you. None of the tools and methods that you find will be safe. But if you are lucky, they may afford you a way to survive.