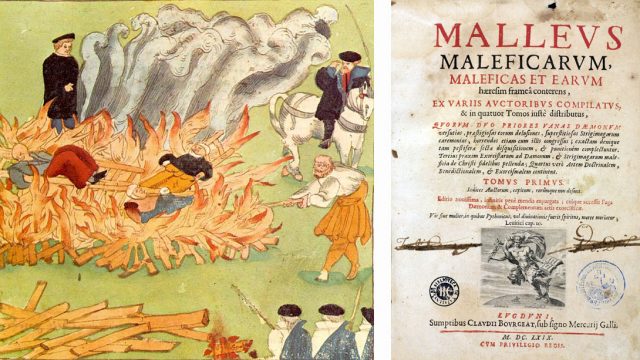

In April 2018, employees of the New York Parks Department forklifted away a statue from the northeast corner of Central Park, where it had stood, opposite the New York Academy of Medicine, for 84 years. It now lies in storage, awaiting its installation in a less prominent location. It is the bronze likeness of James Marion Sims, a nineteenth-century physician who is now best known for his experimentation on enslaved women and his design for a vaginal speculum. Activists had pushed for the removal of the monument, which had come to be seen as glorifying racist violence in medicine.

Between 1845 and 1849, Sims carried out gynaecological experiments on the bodies of enslaved Black women. He developed new surgical techniques to repair obstetric fistulae, which occur during childbirth when a baby’s head presses against the walls of the vagina for prolonged periods, cutting off the blood supply and eventually producing holes through which urine or faeces can enter the vagina. While basic anaesthetics were available at the time, Sims did not use them while slicing and suturing the flesh of his patients. The myth that Black people have higher pain thresholds was widespread at the time. It allowed those whose wealth relied on physically harming Black people to absolve themselves of the need to contend with empathy or guilt. Like many convenient falsehoods, it took on a life of its own and persists in modern medicine. A 2016 study showed that some medical students and doctors still believe, against all evidence, that Black people’s nerve endings are less sensitive and their skin thicker.

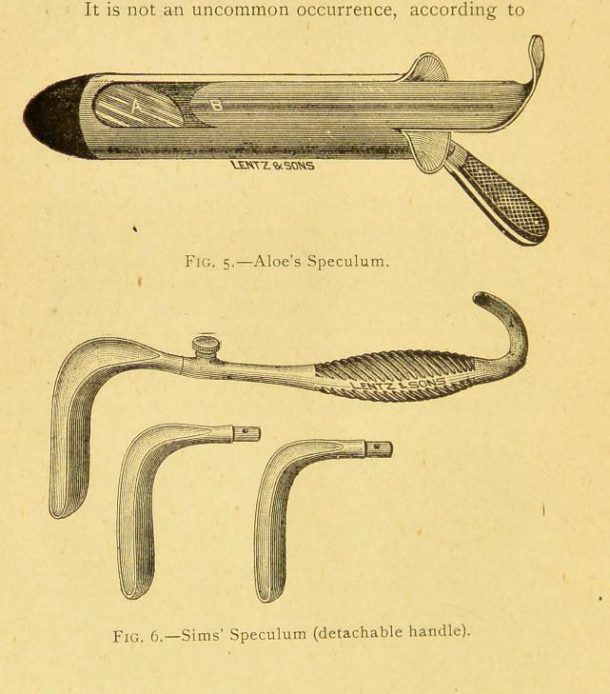

Sims’ second claim to fame is developing a medical device that was the forerunner to the modern vaginal speculum. His version consisted of a bent pewter spoon, which was used to hold open the vagina, and some cleverly arranged mirrors to view its internal structures. The modern speculum has a distinctive ‘duck-bill’ design. A disposable transparent plastic variant is most commonly used by clinicians to examine the vagina and facilitate the collection of cells from the cervix to test for abnormalities that could lead to or indicate the presence of cervical cancer. It is estimated that 4,500 lives are saved every year by the NHS cervical screening programme, which would not be possible without the assistance of a speculum.

Yet the speculum has many meanings. Obviously, it is linked to Sims, whose scientific fame was built on his easy access to the bodies of Black women and the pain he felt entitled to inflict upon them. But also, those into whose intimate body parts it peers – cisgender women, transgender and gender non-conforming people – have often had difficult encounters within medicine, which is still centred on the needs of white, cisgender men. As mentioned above, the underestimation of the pain of marginalised people is not a thing of the past, and studies show women and Black people wait longer for pain medication and often have their pain discredited. And, of course, the use of a speculum is physically uncomfortable and can feel embarrassing and violating.

The open-source 3D-printed speculum championed by the feminist activist group GynePunk is an attempt to move away from this history and these associations. The idea of a speculum you can print and use outside medical settings represents liberation for marginalised bodies from the gaze and neglect of conventional medicine. It symbolises a rejection of the oppressive features of medicine and the desire to work outside its paradigms.

But this raises important questions about what we do with the objects that trouble us. Sims’ statue was removed because such monuments bestow honour, and to honour him is to dehumanise Black people. We had nothing to lose in toppling him and everything to gain in terms of liberating public space from his imposing shadow and its whitewashing of history. What about the speculum? Should we reject it and its conventional uses as a way of protesting the treatment of marginalised people within medicine, and the shameful history of the instrument’s development? What might we gain, and what do we stand to lose?

A speculum is not a monument. It’s a tool, an object whose use, unlike a statue, is not primarily representational. It may sometimes be charged with representing medical patriarchy, but this must be weighed against the lives it saves. Medicine and its lifesaving devices, including the speculum, are the products of a long history that is often told as tales of the (often questionable) triumphs of ‘great white men’. But that’s a distortion of the facts. Scientific discoveries and inventions have always been communal achievements. They are made possible by the largely invisible labour of working-class women, and the social inequalities leave some people free to think and play while others toil. And in some cases, they rely on the bodies of nonconsenting marginalised people.

Rejecting medicine cedes too much. It may be a troubled paradigm, but it belongs to all of us, and we should seek reparation within it rather than resisting from outside. Marginalised communities deserve healthcare that centres their needs, not only as recompense for past and present injustices, but because marginalisation is itself a determinant of ill health. We have to start telling the cruel history of the speculum and demanding justice in healthcare, but we must work from the centre, not the margins, and take back what is all of our inheritance and due. Sims must fall, but the speculum can be reclaimed.