Can you tell us a bit about who you are and what you do?

I am a community sexual and reproductive health doctor, academic, founder of non-profit, Decolonising Contraception and soon-to-be author of Decolonising Healthcare. I have been interested in health inequality since I was at medical school often, writing about the global differences in access to medications, especially around HIV. Yet, towards the end of my medical training, I realised how profound the health inequalities are on our doorstep and how we have not even begun to examine some of the more uncomfortable reasons such as race, class and colonialism that make these differences so dramatic. I was drawn to the specialty because of the inequality and the many opportunities to improve the situation.

Why did you agree to take part in the 3D-Printed Speculum Project?

This project began pre-COVID, and never did we all think that so many of the themes that come through in the project – health inequalities, equal access to healthcare, sexism, racism and so many others – would be in the headlines as they are. Anouska’s exploration of GynePunk’s work and the speculum provided an opportunity to open up a much-needed conversation on the history of modern gynaecology and how it operates today, to a wider and more diverse audience. Although the project has changed over time, it has brought together a wide variety of people. Through all the workshops and discussions, I have learnt a lot and it has also allowed me to reflect on my own health activism and what shape that can take.

As a clinician, what does the speculum mean to you and how does it make you feel?

The duckbill speculum is an instrument that I use almost every day. It’s my wingman [laughs]; it enables me to examine vaginas when people present with pelvic pain, abnormal discharge and even miscarriage. By using the speculum, I can put a patient’s mind at ease when they come with anxiety and questions. A few months ago, I had a beautiful encounter with a patient who had undergone genital cutting as a child and required a cervical screening. She had always avoided them previously, but we managed to do it that day. She said it was one of the most positive experiences she had ever had. I am grateful that I have a tool at my disposal that allows me to help so many different people.

But it is also an instrument that many people also associate with trauma, and it does have an ugly history; furthermore, the design is geared towards working for clinicians rather than patients. I’m very tuned in to the fact that some patients have a poor relationship with speculum examinations – some even tell me at the start of the consultation and are visibly anxious. Others don’t say anything, but it’s obvious if they are very tense. I have examined those who have gone through trauma, including those who have undergone genital cutting, and I always feel a huge sense of responsibility with each examination – particularly if they have never encountered a speculum before. I do not want to scare them, and I want to ensure they will attend future appointments. I am currently studying psychosexual health too, so all the interactions in the room have become even more important to me.

How do you think the design can be improved?

There are quite a few problems with cheaply made plastic speculums: there could be a better size variety; sometimes the screw can catch the vulval skin if the user isn’t careful; they could be softer. I’m sure most people who have experienced examination with a speculum can think of a few things they didn’t like about the instrument.

What would you like your fellow medical professionals to know about the speculum?

Those who use the speculum regularly, such as gynaecologists and sexual health doctors, are likely to have considered it from a patient’s perspective. Yet, I think there is so much that many health professionals have never considered regarding the duckbill speculum. That the hard plastic, whilst economic, is pretty uncomfortable and something softer would be much nicer. We could probably design something that allowed patients to better assist in inserting the speculum.

How do you think the history of gynaecology relates to the design of the speculum?

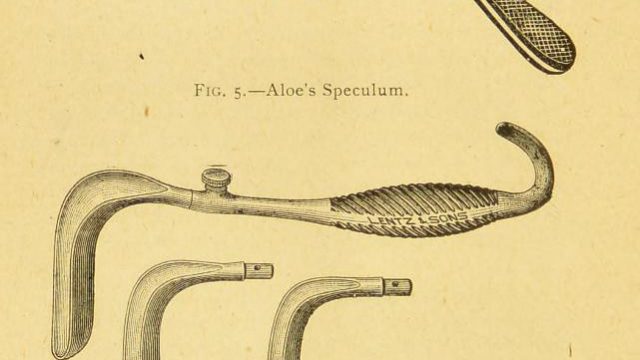

Most people, including health professionals, know very little about the history of medicine. Yet, it is so important to how we experience healthcare today. Recently, more people have been made aware of the history of J. Marion Sims, referred to as the American forefather of gynaecology. His practice in the Southern Antebellum era of utilizing enslaved Black Americans as test cases is shocking, but it also allowed for the advancement of medical science. Sims is considered the pioneer of the speciality carrying out some of the earliest vaginal fistula repairs (a complication where a connection is caused between two surfaces often due to prolonged birth). He actually has a different speculum named after him, the Sims speculum, which is more often used in theatre. Recently, a spotlight has been shone on him because he exploited Black, poor and mentally ill women for his experiments. A few years ago, a statue of him in Central Park, New York, was removed, and there have been petitions launched in the UK calling for the removal of other Sims memorials.

Yet, few people are aware that the slaves he experimented on also assisted him during his surgeries; he would not have made these discoveries without them. That part of the history is expunged and these women are portrayed exclusively as unintelligent victims, but the narrative is far more complicated than that. These women were exploited, but they were also pioneers in their own right. There’s a great book on this subject by Deirdre Owens called Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology. It is also very reductive to examine this particular history without examining the history of medicine as a whole. We would not have modern medicine without colonial conquest and the contributions of marginalised groups. We now know that not only did ground-breaking discoveries depend upon them as subjects, but also that many revolutionary ideas – from early vaccination to the use of forceps during delivery – were taken from them without credit. There is so much we, myself included, don’t know about the history of medicine. And I believe a deeper knowledge would change people’s perceptions about what healthcare is.

How do you think the work of Decolonising Contraception helps in this area?

I founded Decolonising Contraception about four years ago because, despite the clear differences in how some marginalised groups were experiencing reproductive healthcare, there was a real silence about why. I also wanted to find like-minded people with whom to have these conversations. I feel that’s how real change happens, not by talking about what has already been discussed thousands of times before. This is something that I like about this project, too – GynePunk’s work is innovative. Even if other groups might approach things differently, there’s a whole conversation that they are starting about design and usability. I think there’s room to remind people that women were involved in the creation and design of these tools beyond lending their bodies to medical science, and really thinking about how we should centre the patient’s perspective, not just in the speculum’s design, but about other gynaecological instruments too.

What do you want for the future of gynaecology and the speculum?

For me, I want inclusive care. I don’t think people can easily understand what it means to be inclusive when they have always been included. Nonetheless, we continue to see awful statistics (studies here, here and here) regarding gynaecological cancers and STIs disproportionately affecting poorer people of colour, and we have made no progress in improving the situation in decades. I am ready for progress now. One way of doing this is to question some of our basic assumptions about how we practice medicine.