Vagina.

Vulva.

Virginity.

Unmarried.

Honour.

Shame.

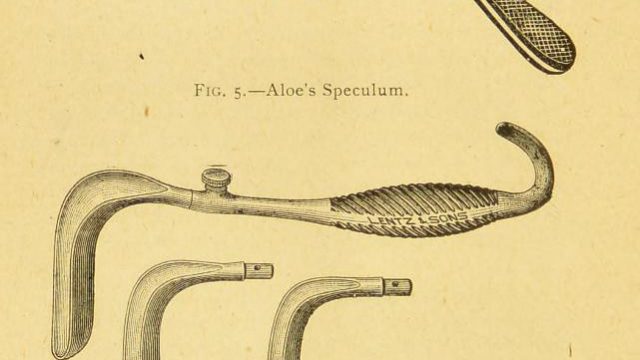

Through my work with survivors of sexual violence, FGM, virginity testing and harmful practices, I have identified a strong link between the words that come up in people’s minds when discussing access to sexual and gynaecologist healthcare and the speculum. The speculum is an object meant to offer support, but it nevertheless remains an emotive object that still can cause trauma to people, and in particular people of colour, today. Yet the speculum’s history is littered with deep feelings and pervasive myths that reflect the cruelty of its development. This ongoing emotional experience also reveals all the social norms that prevent some people from accessing appropriate, sensitive and adapted healthcare.

Several Black and Brown communities lack access to sexual and reproductive healthcare because the system does not meet their needs, beliefs and, sometimes comfort. Intergenerational trauma is also a reality that must be taken into consideration when discussing gynaecology, the design of the speculum, and the long history of medical tests on enslaved people, Jews and those in colonised countries.

In several communities, the bodies and virginity of young girls must be protected from any ‘non-husband’s’ hands and eyes, as they must remain pure. Virginity is strongly perceived as an invisible social status, protecting people from anything that could contaminate it outside marriage and, therefore, ruining the family’s reputation. It is not uncommon to hear testimonies from women describing how a sexual disease or condition was left untreated during their younger years because of the refusal of their mothers, or other women in the family, to take them to a gynaecologist. Doctors are normally considered to be for married women only, and health issues relating to sexual intercourse outside marriage are often ignored. Speculums are also perceived as a tool that will ‘take away virginity’, possibly endangering a girl’s reputation.

Virginity myths are not the only reasons why certain communities refuse the speculum or resist unmarried women visiting gynaecologists. Health systems can also participate in discriminatory practices and exclude people from accessing healthcare. Institutions such as hospitals, medical centres or clinics can be racist and non-inclusive towards people of colour and LGBTQIA communities. People of colour have raised complaints that they have been treated badly, that their pain was underestimated, and that doctors were convinced that they would experience suffering differently from their white counterparts. Often people were denied access to medicine or their description of symptoms were not taken seriously. This is known the ‘Mediterranean Syndrome’, wherein people of colour are accused of exaggerating their symptoms or concerns that doctors are not giving them adequate healthcare. This is often because of a lack of understanding of bodies that are not white and how they may react differently (for example, skin cancer is often diagnosed too late for adequate treatment in Black people). Often the consequence of this is a lack of trust between communities towards a health system that participates in marginalizing them and violating their rights.

Rethinking the speculum and the access to healthcare is a promising project, but it must simultaneously be done with the restructuring of the system (which also includes the educational institutions producing the future healthcare professionals). Sexual and reproductive rights must not only be inclusive but decolonised, and they must adapt to the needs of all patients: culturally, religiously, sexually and based on identity. In the twenty-first century, one can no longer perpetuate the violence and exclusion that activists and survivors have been denouncing.

However, challenging the narratives and tools used in modern gynaecology must become a priority for activists and medical professionals. It is an object that extends beyond the enclaves of the women’s liberation movement, overcoming trauma and stereotypes around this tool, and beyond those who might not have found a home within this movement – in the past and in the present. The GynePunk project specifically includes trans and non-binary people, people of colour and working-class people. However the GynePunk Speculum itself remains an object that can be used by those who have access to the equipment needed to produce it and improve its design, as explained by contributor Antonia Pontiki in her work on this project.

Therefore the 3D-printed speculum may be inaccessible to those most marginalised, and to those who may not always be included in left activist spaces. The political intention behind the 3D-printed speculum, and the additional work of Klau, founder of GynePunk, is powerful. But in order to try and address questions of access and safety, the design itself must think of other ways of making these tools of production accessible too.