The earliest town model of Basel is from the 19th century and displays only part of the city. The sculptor Karl Albert Bastady was commissioned by the building authorities and created it presumably in 1895. It showed an area between the Schifflände (ship landing) and the Petersgraben (former city moat), which had been severely altered some years before by the building of a new street (the Marktgasse).[1] This model was on display in the Swiss Landesausstellung in Berne in 1914, after it had been restored by the engineer Gustav Nauer. Alongside this the restorer seems to have been encouraged to build his own model, showing the area around the Barfüsserkirche (Franciscan church), at the time of “about 1870”.[2] The work was finished in 1926. “About 1870” was chosen for two reasons: Firstly, at that time the official cadastre was introduced, together with a newly measured cadastre plan, which displayed each parcel in the scale of 1:500. Hence an excellent basis of measurement for the work was available. Secondly, both models show the town before the immense changes that were undertaken at the time of industrialization, especially after the tearing down of the city walls and the sprawl of the suburbs, which caused alterations in the inner city as well. Thus the motivation lay in the desire to document the threatened or already changed building stock of a medieval town, just like the countless sketches and watercolours of the so-called Kleinmeister (small masters) that depict all kinds of picturesque corners. Both models soon belonged to museums in Basel.

Only a few years later models were used as instruments for town-planning in Basel. They served as advertising elements in a democratic process. From being often hidden objects in princely cabinets of curiosities, expressing power and ownership, models turned into tools with greater persuasiveness than 2D-plans. The debate centred on the “Sanierung” (redevelopment) of the old town in the 1930s/1940s. The houses within the medieval walls were at that time intensively used because of overpopulation in the 19th century. Awkward living conditions were common. In Basel’s city centre new commercial houses and whole areas had been constructed about 1900. On the other side voices arose which demanded the preservation of the old town.

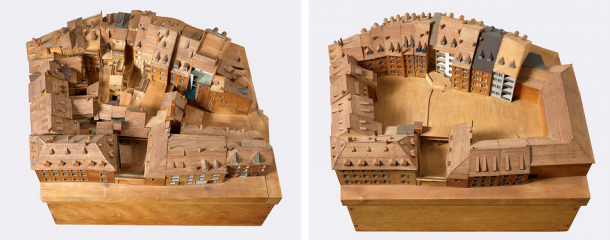

Initially in 1939 some “Altstadtzonen” (preservation zones) were legally defined, in which building improvements were planned. Sanitary and proper living spaces were to be created, together with a seemingly undisturbed image of the old town, purified from the distorting annexes and alterations of earlier periods. In preparation the current state was documented photographically and graphically. An exhibition called “Altstadt heute und morgen” (the old town today and tomorrow) presented the plans to the public in 1945. For this occasion the model-builder Walter Studer made several models of boroughs, showing the state “before” and “after” redevelopment. First of all the backyards were to be liberated from intricated buildings. Most of the planning of that time was not executed, luckily.

This notion of a redeveloped (“purified”) old town has significant similarities with the image of the town represented by plan veduta and models in the Renaissance (i.e. in Basel Merian’s plan veduta from 1615, see Thinking Towns Part 1). Not accidentally, only a few years after the said exhibition, there was a new town model built in Basel, in the same museum! It was created between 1952–1959 by Alfred Peter, an assistant of the Denkmalpflege (preservation office), and shows Basel at the beginning of the 17th century, in a scale of 1:400.[3] The most important source for Peter was Merian‘s plan veduta. Several features of the printed image were somewhat corrected, for instance the widened streets and the perspective executed in accordance with importance, by which Merian stressed the Münster and other important houses. The model also represented the topographic relief of the landscape and it was coloured. Thus the 20th-century model seems to be closer to reality than the contemporary image from 1615. It lures the visitor to undertake a journey back into the past and calls on Merian as an eye-witness. But nonetheless, despite its precision and detailed work, it cannot evoke anything more than a mental image of the town as it was drawn in the 17th century.

This problem is faced by all virtual town models that are created on the basis of older physical models. In Geneva the 1896 finished model of Auguste Magnin “Geneva at 1850”, has been turned into a fascinating animation, free to visit online (http://www.geneve1850.ch). The motivation for building this virtual model is similar to the Bastady model in Basel (Fig: 1), i.e. to show a threatened or already lost historic environment. Nevertheless it isn’t possible to digitally display every piece of information about historical buildings as displayed in the model, either on the internet or through an interactive touchscreen-monitor in a museum.

The modernizing or reanimation of model-building, heralded by 3D/virtual-reality technologies, opens up the chance for researchers to engage with the historic shape of the city anew. With 21st century techniques it’s possible to consider and make available in one place the results of decades worth of archaeological and preservation research. For example, research on the Utrecht cathedral tower, published in a book in 2014, shows different stages of the construction, not only of the cathedral and its tower but also of the city around it, by means of computer generated 3D models. It was necessary to reconstruct the whole process of building over a considerable period of time for this project. The virtual 3D-models were on display in an exhibition in Centraal Museum Utrecht in 2016.[4] The Kantonale Denkmalpflege Basel-Stadt is currently working in cooperation with the Grundbuch- und Vermessungsamt on building a 2D-townplan reconstructing the city shape at Merian’s time, which will hopefully be useful for later projects, such as a 3D-model of the historic city.

[1] Brigitte Meles: „…aufgelöst 1996“. Das Basler Stadt- und Münstermuseum im Kleinen Klingental 1939–1996 (176. Neujahrsblatt der Gesellschaft für das Gute und Gemeinnützige). Basel 1998, p. 52 f.

[2] Historisches Museum Basel, Inv.-No. 1927.10. See http://www.hmb.ch/sammlung/object/stadtmodell-barfuesserplatz-und-umgebung-um-1870.html?no_cache=1.

[3] Basel, Museum Kleines Klingental, Inv.-No. -12431.

[4] René de Kam, Frans Kipp, Daan Claessen: De Utrechtse Domtoren. Trots van de stad. Utrecht 2014. See https://centraalmuseum.nl/bezoeken/tentoonstellingen/trots-van-de-stad-de-utrechtse-domtoren/

To find out more about the network visit our project page.