A is for aventurine

Made purely by chance by a Muranese glassmaker in the early 16th century, Aventurine is a dazzling translucent green or brownish glass with glittering metallic inclusions. To create the glinting effect, copper oxide, or cuprous oxide as well oxides of lead, tin and iron are added to the batch of molten glass. After many hours of heating the batch, it is vigorously stirred, the furnace openings are closed, and the fire is extinguished. This creates an oxygen-starved ‘reducing’ atmosphere which causes the development of tiny copper flakes suspended in the glass. When cooled, these reflect the light and give a mottled, sparkling gold effect. The mineral gemstone, also called aventurine, displays a similar effect to this glass.

B is for blowing

This technique involves inflating a gob (round blob) of molten glass on the end of a blowpipe. To gather a gob, the conical 'nose' of the pipe is preheated, dipped in molten glass inside the furnace, rotated, and withdrawn. The gaffer (person carrying out the blowing) shapes the gob using a either a marver (a smooth, flat surface that the softened glass is rolled and shaped on), a block, or a pad of damp paper, and blows through the pipe to form a bubble called a parison. Free-blown glass is shaped by manipulating the parison using gravity, centrifugal force (by swinging the pipe), and tools such as jacks, pincers, or shears.

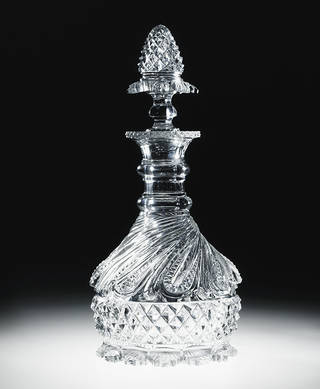

C is for cutting

Cutting is a decorative technique which requires removing glass from an object. A rotating wheel of stone, wood, or metal, fed with water and an abrasive powder is used to grind away part of the glass surface to form abstract patterns. After cutting the patterns, the glass needs to be polished with softer wheels made of wood, cork or felt. Although the earliest cut glass dates to about 720 B.C., the technique wasn't used extensively before the Roman period. New types of very clear colourless glass that were developed during the late seventeenth century in Europe proved to be ideally suited for deep cut decorations. During the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries heavy cut glass with elaborate geometric patterns became extremely popular for table glass and chandeliers.

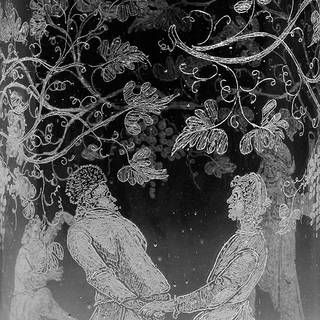

D is for diamond-point engraving

Diamond-point engraving involves scratching a decoration freehand onto the surface of the glass using a small splinter of diamond mounted on the tip of a wooden stick. The engraver must avoid scratching too deeply as this might cause the glass to crack. The technique was introduced by the Venetians in the 16th century but was mastered by the Dutch in the 17th century. During the 18th century, Dutch engravers developed a variation of the technique known as stippling or stipple-engraving. Instead of scratching the glass in linear strokes, they built up the design with innumerable dots by tapping on the surface of the glass with a diamond point.

E is for enamelling

Enamel is a substance composed of finely powdered glass that has been coloured with metallic oxides, mixed with an oily medium, and then applied to a glass object with a brush. Once the enamel decoration has dried, the glass object is either placed in a low temperature muffle kiln for firing, or – as carried out during the Renaissance – reintroduced to the mouth of the furnace at the end of a blowpipe or pontil (metal rod). The oily medium burns away during the firing and the enamel fuses to the surface of the glass. On highly decorative objects, multiple firings may be required to fuse different enamel colours.

F is for filigree

Filigree glassware features internal stripy patterns. The stripes are made by melting glass canes of a contrasting colour into the glass. The canes are produced by stretching a solid blob of molten glass between irons, to form thin lengths of up to 20 metres. Each cane can be broken into sections and re-melted. These canes can either be a single solid colour, or a colourless glass with a coloured core. A colourless cane with an internal pattern of twisted, coloured strands can be created by melting several canes together and twisting them during the stretching process.

G is for gilding

Gilding involves decorating a glass object by applying gold leaf, gold paint, or gold dust to its surface which is then fused during firing. Gilding can be applied in numerous ways: gold can be combined with mercury to form an amalgam that can be painted onto the surface; gold leaf can be applied using a glue named 'water size'; or gold leaf can be picked up on the hot glass when being shaped on the marver before the object is blown.

H is for hot working

Manipulating glass while it's hot is known as hot working. This is usually done by the master glassblower who works the glass in front of the furnace. Tools such as jacks, pincers, or shears are used to shape the hot glass, making sure that it remains soft and workable by constantly reheating it in the mouth of the furnace, or ‘glory hole’. The master glassblower works with assistants, who can gather additional hot glass from the furnace to be added onto the piece that the master is working on. When two different parts of hot glass touch, they immediately fuse together. This method is used to attached features such as handles, stems, feet and other decorations.

I is for iridescence

Iridescent glass features a rainbow-like visual effect that changes according to the angle it is viewed from or the angle of the light source. Ancient glass often appears iridescent, although this was caused by weathering rather than being the intention of the glassmakers. During the 19th century, glassmakers learned how to replicate this effect by exposing the hot glass to metallic fumes. By spraying iron chloride or stannous chloride onto the hot glass surface, different results could be achieved. When the glass is very hot the iridescence becomes matt, and when it's slightly cooler, the iridescence is vivid. The effect was especially popular with Art Nouveau glass artists and is most often associated with the work of the American painter and stained glass artist Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848 – 1933).

J is for joke glass

Joke or trick-glasses are typically used for drinking 'games' where the aim is to puzzle and amuse participants and ensure a generous flow of alcohol. Usually there is a hidden way that the glass needs to be used in order to operate it successfully. In the case of this 'syphon' glass, liquid can only be obtained by sipping from the hole in the stag’s mouth while simultaneously placing a finger over a hole in the hollow stem, which is concealed as one of three ornamental ‘prunts’ (small blob of glass fused to another piece of glass). If the next drinker attempts to drink without blocking the hole in the stem, they will just draw air from the stag's mouth.

K is for kiln fusing

'Kiln fusing' or 'mould melting' is a technique whereby a plaster mould is filled with small pieces of glass or ‘cullet’. The mould is then placed in a special kiln over a long period and the glass inside melts and fuses together, filling the entire mould. Before the mould can be taken out of the kiln, it needs to cool down very slowly to avoid internal tension inside the glass. The surface of kiln fused glass is dull and so it is often partly polished to return the transparency.

L is for lampwork

Lampworking forms objects from rods and tubes of glass by heating them in a flame. As lampworking only requires a simple torch, it was often practiced as a cottage industry – traditional mould-blown Christmas decorations were, and still are, made in this way. Young contemporary glass artists are increasingly drawn to this technique as it does not require an expensive furnace or kiln, or a fixed location.

M is for marbled glass

Marbled glass is decorated with streaks of two or more colours, resembling marble or semiprecious stone. This involves briefly stirring the glass to achieve a swirling effect, whilst ensuring that the colours don't blend. A special variety of this technique was developed in Venice around 1460 called Calcedonio or 'chalcedony glass', as it resembled a naturally occurring hard stone of the same name. The technique required complex heat-treatment during hot working and was a closely guarded secret for centuries.

N is for network glass

Network glass or ‘vetro a reticello’, in Italian, is a complex type of filigree glass. A beaker-shaped vessel is prepared, made of colourless glass canes with an opaque white core. The simple stripy pattern is achieved by twisting the glass and canes in one direction to create a spiral effect. The beaker is kept hot, while another filigree bubble of glass is blown. This is then twisted in the opposite direction. The bubble is lowered into the prepared beaker and inflated, so that the two layers fuse together, creating the criss-cross network pattern.

O is for overlay

The simplest and most common overlay is 'flashing' – gathering a blob of molten glass on the blowpipe and gathering a second layer of differently coloured glass to cover it. 'Casing' involves making an outer case of hot glass by opening a bubble to form a bowl-like shape, which is kept hot. Another bubble of a different coloured glass is then inflated inside the bowl. With both techniques, the layers fuse together and can be further inflated and manipulated. As the resulting bubble is inflated, both layers become progressively thinner. An overlay is often used in combination with engraving, etching or sand-blasting, which removes the outer layer, revealing the contrasting colour underneath.

P is for prunt

This is a small blob of glass applied to a glass object during the hot-working process. Prunts are primarily decorative, but can also have a practical purpose. During the Middle Ages and the Renaissance period – when diners often ate with their hands, rather than forks – they were a useful feature on drinking glasses as they provided additional grip for greasy hands. Prunts were usually embellished by using stamps to give a decorative relief pattern, or could be pinched and pulled with simple tools.

R is for reverse painting

Painting a design on the back side glass is known as reverse painting. As the design is viewed through the glass, the pigments must be applied in the reverse order, beginning with the highlights and ending with the background. The technique is also referred to by its German name, Hinterglasmalerei, meaning 'painting behind glass'. Unlike enamelling, the pigments are not fired, which makes them unstable and susceptible to damage. Reverse painting had been popular in Europe since the Renaissance period. During the 18th and 19th century, Chinese decorators painted oriental scenes on glass panes imported from the west, which were then re-exported to Europe.

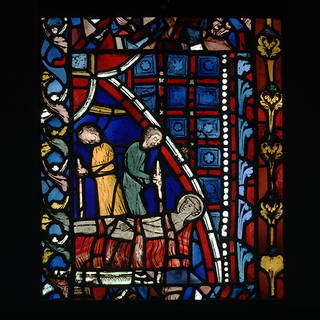

S is for stained glass

Stained glass is the name for decorative windows, often found in churches, that are made of pieces of glass fitted together with thin strips of lead called ‘came’. To achieve different colours, overlaying was used. Painted decoration could be applied to the glass pieces which were then fired in a kiln before fitting them into a design. Early stained glass was often painted with ‘grisaille’ – a greyish black enamel with a high lead oxide content – to achieve a monochromatic design. Silver stains painted on the reverse of colourless glass pieces created a beautiful golden-yellow colour after firing, from which the term ‘stained glass’ derives.

T is for trailing

Trailing is a specific type of hot-working. It involves the decorative application of threads of molten glass (called trails) to the body, handle, or foot of a vessel. An assistant drips molten glass, like honey, from the end of a blowpipe onto the piece the master glassblower is working. The master rotates the work so that the trail becomes a neat spiral around the body.

U is for uranium glass

The fluorescent yellow-green colour of uranium glass is achieved by adding uranium oxide to the glass mixture or ‘batch’. It was developed by the Bohemian glassmaker Josef Riedel during the 1830s, who named it after his wife, Annagrün [Anna Green]. As this glass contains small amounts of uranium, it's slightly radioactive.

V is for Venice

Venice has been well known for the production of the finest glass for many centuries, with the very first evidence of glassmaking in the Venetian lagoon dating from the 7th century. During the medieval period, glass became the most important Venetian export. The industry was organised in a guild of glassmakers and their first set of regulations dates from 1271. Twenty years later, it was decreed that all new glasshouses should be established on the island of Murano, which is where the craft then flourished. The Venetian state encouraged glassmakers to use the best ingredients and rewarded technical developments and inventions, which included the finest colourless glass, filigree glass, chalcedony glass, amongst many others. Such secrets were tightly guarded, to ensure that Venetian glass remained the finest that could be bought. From the second half of the 16th century, Venetian glassmakers travelled abroad to set up glasshouses and continue their work in this style.

W is for wheel engraving

Originally adapted from carving hardstones in the early 17th century in central Europe, wheel engraving involves cutting into the surface of a glass object using small rotating copper wheels that are fed with an abrasive paste. The resulting relief is usually left matt, so that it contrasts with the shiny surface of the glass. Engraving lathes were originally treadle-operated (a lever operated by foot), but since the late 17th century have also been powered by water. Such powerful lathes allow for deep-cut decorations in which, sometimes, the whole surface of the glass is engraved. In that way a positive relief can be created, using a technique called ‘Hochschnitt’, or relief cutting. This contrasts with the standard technique of cutting a negative relief into the surface of the glass, known as ‘Tiefschnitt’, or 'intaglio'.

Z is for zwischengoldglas

Zwischengoldglas is a widely adopted German term which can be translated as 'gold sandwich glass' and is a type of decoration that was used in Bohemia, Germany and Austria during the 18th and 19th centuries. It required two glasses – one fitting snugly inside the other. Gold or silver leaf was applied to the outer face of the smaller glass and engraved with a metal tool to form a design. The two glasses were then joined together, and the junction at the lip was ground smooth and sealed with a cement. This technique is different from Hellenistic or Roman gold glass, which involved melting the layers of glass together in a furnace after the gold-leaf had been applied.