Art Deco readily embraced folk art traditions, therefore designers around the world could adapt their native decorative forms, to help create a modernised national identity. In Sweden, for instance, the influence of native art is vivid in Edward Hald's delicately engraved glasswork, depicting scenes of contemporary city life while making a clear nod towards the Swedish engraved glass tradition.

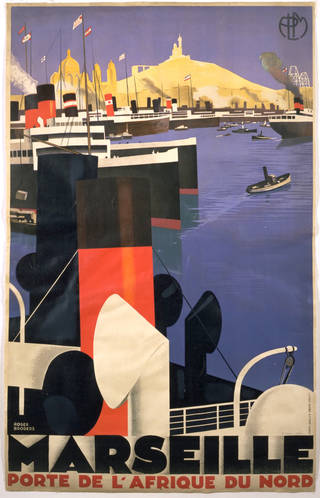

In many parts of the world, Art Deco stood for escape. It offered an accessible image of modern life, more fun than it’s functional sibling, Modernism. The expansion of the travel industry played a key role in enlivening Art Deco's associations with escape and glamour. As the wealthy elite travelled the world in luxury Art Deco ocean liners, advertising posters sold the ideal to the masses.

Posters such as 'Marseille Porte de l'Afrique du Nord', designed for the French Railway Company, the Paris-Lyon-Méditerranée (PLM), used Art Deco's simplified lines and bold colours to promote tourist destinations. An image of a busy harbour, with shiny black ships floating side by side, their flags hoisted high, not only glamourises travel, but also the modern machinery that made mass tourism possible.

Across the globe, in the rapidly developing country of Japan, travel posters had a similarly powerful influence. Private companies and state railways competed to build ever faster and more comfortable trains, triggering a proliferation of striking marketing material. Art Deco, with its readiness to combine elements of tradition and modernity, was a popular stylistic choice. Munetsugu Satomi's poster encapsulates the mood in Japan at the time, with its traditional signifiers of Japanese identity, such as the cherry tree, side by side with icons of industrial modernity, such as the railway and telephone masts.

In the 1930s, Shanghai was the most fashionable city in China – and also the most technologically advanced. The steel and wood Art Deco clock in our China collections captures this dynamic spirit. The market for this type of goods would have been either a Chinese person eager to adopt a western lifestyle, or a Westerner living in China.

As Europeans emigrated to the US and American designers travelled to Europe, the profound and extensive American Art Deco scene emerged. European idiosyncrasies were quickly superseded, as US designers strove to 'Americanise' the aesthetic, adapting it with cheaper materials, machine production and American social habits. The most enduring of these adaptations was streamlining. Originally inspired by the speed and efficiency of machine-age travel, aerodynamic curves and economic lines weren't just applied to transportation, but to architecture and consumer goods, such as the Ronson cigarette lighter.

Streamlined forms, which often involved encasing products with contoured shells, lent themselves to mechanised mass-production and new materials such as plastics. The Patriot radio is a typical example, showcasing plastic's exciting design possibilities.

Plastics allowed the decorative appearance of radios to be enhanced through trim. Tuning knobs, dial parts and handles were often cast separately in a contrasting colour. The Patriot shows this brilliantly with its dial and speaker grills picked out in white and red, and the tuning knobs a different shade of blue. This design was produced in varying combinations paying homage to the American flag. Read more about Art Deco in the home

For all its optimism, streamlining marked the last phase of Art Deco's rich story. Its unfettered consumerism culminated in the New York World Fair of 1939. The Fair's streamlined and geometric buildings celebrated the American dream in the face of totalitarianism and war in Europe.

Six years later, when the Second World War finally ended, the world was very different. Ornament came to be regarded as unnecessary and the splendour and flamboyance of Art Deco gave way to austerity, rationalism and functionalism. Its global legacy still stands out, however, in the buildings and artifacts it embodied.