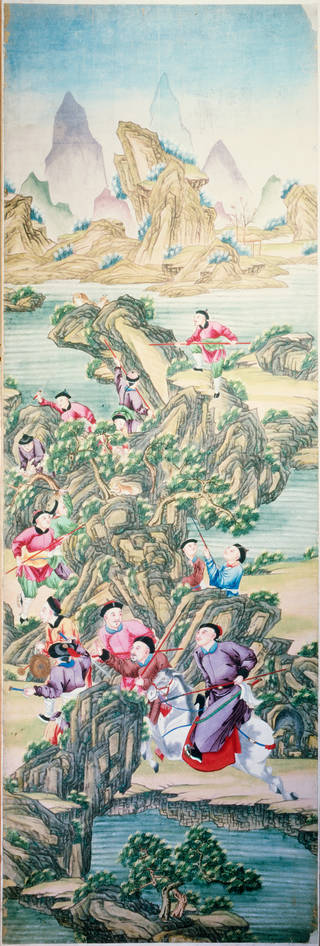

Chinese wallpapers were supplied in sets of 25 or 40 pieces, each different in design, which could be hung to form a continuous mural decoration around the room. With their exotic subject matter – scenes of Chinese life and landscapes, or flowering trees populated with birds and butterflies – and their rich hand-painted colours and fine detail, they were unlike the wallpapers available in England at that time. Costly in comparison to locally-made wallpapers, they were bought and hung by the wealthy.

Chinese wallpapers arrived in England as part of the larger trade in Chinese artefacts, such as lacquer, porcelain and silks, that were imported by the East India Company – the British company formed to trade with East and Southeast Asia, India and China. The Chinese did not use painted papers like these as wall coverings, preferring them plain – usually white, crimson or gold. It was Chinese practice though, particularly in the trading ports of Canton and Macao, to paste paper over windows and paint pictorial decorations. It may be that these were admired by European merchants, which promoted the Chinese to produce similar decorations for export.

The popularity of these Chinese papers (despite their cost and the availability of quality locally-produced papers) was part of a wider 'Sinomania' – a fashion for all things Chinese. The appetite for oriental exotica was fed by the import of Chinese decorative goods and written accounts at the time that presented China as a sophisticated model society to rival Greece or Rome.

The enthusiasm for Chinese styles was reflected in their widespread use in 18th-century decoration. There was a playfulness and informality in the style that made them popular decorations for bedrooms and apartments, especially those used by women.

But the enthusiasm for Chinese papers was not universal. A taste for Chinese styles became associated with the nouveaux riches who had made their money in trade. As the English poet William Shenstone put it, "A mere citizen is always aiming to show his riches…and talks much of his Chinese ornaments at his paltry cake house in the country". Chinese wallpapers became associated with a vulgar parade of wealth, rather than with elegant and refined tastes. Some also saw the Chinese imported papers as a threat to the livelihoods of English textile workers.

By continuing to pay close attention to the tastes of the European market, by modifying designs and introducing new patterns, motifs and colours as required, Chinese wallpaper manufcaturers prevented the trade from stagnating.

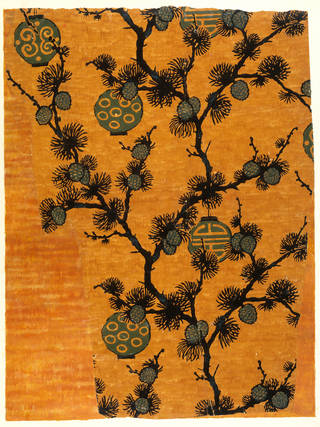

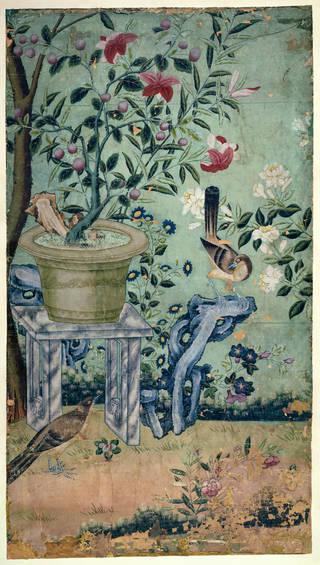

The earliest papers to arrive in Europe depicted scenes of daily life and industry in China in a variety of landscape settings. Another main class of Chinese paper was the so-called 'bird and flower' type, characterised by sinuous flowering trees, with birds and insects among the branches, all silhouetted against a coloured ground. Later modifications of this design introduced figures in the foreground, flowering shrubs in pots, and birdcages suspended from the branches above.

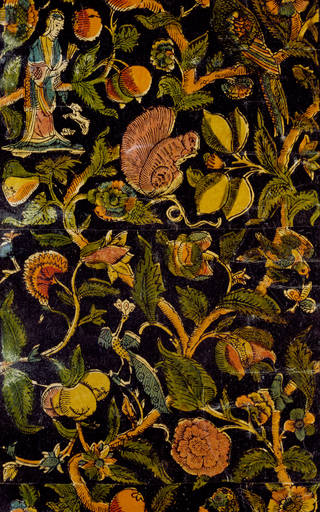

Chinese papers were relatively expensive and orders for specific designs or colourways could take up to 18 months to be delivered. It was not surprising then that English and French manufacturers sought to capitalise on this new fashion by producing imitations. The earliest examples demonstrate a poor understanding of the conventions of the Chinese designs. One early attempt from our collections dates from about 1700 and was found in Ord House, Berwick-on-Tweed, Northumberland. Unlike the Chinese originals, it is a repeating pattern with Chinese figures dwarfed by parrots and red squirrels, all set haphazardly amongst crudely drawn branches.

In our collections we also have examples of unused single-sheet papers. Compared to genuine Chinese papers, these single-sheet paper designs are badly drawn, include inaccurate depictions of Chinese flora and fauna, buildings and costumes, and even include animals, such as dragons and camels, that never appeared in Chinese wallpapers. Some papers appear complete in themselves and others have motifs that are cut off at the edges of the sheet suggesting that they were to be hung in overlapping sequence with others.

By late 19th century the taste for Chinese wallpapers had declined though oriental styles did come back into fashion for a brief period in the 1920s. The style continued to filter down to more modest homes as machine-made prints with loosely 'oriental' patterns of birds, flowers and paper lanterns in bright colours.