Huguenots were members of the Calvinist Protestant tradition and as such were a minority in Catholic-dominated France in the 1500s and 1600s. Barred from many other professions, they became highly skilled makers, developing sophisticated techniques for embellishing precious objects in order to stand out in a competitive environment. Many of these craftsmen fled France under the threat of religious persecution and economic uncertainty, and went on to establish centres specialising in goldsmithing and metalworking in cities across Northern Europe. Luxury goods made by Huguenots were exported worldwide – many objects in our collections are the products of these networks of refugee makers spread across the continent.

Watch cases

Blois, in the Loire Valley region of France, was an important production centre for silver, watches and jewellery – a craft dominated by Huguenot makers. Watch cases were initially engraved with pattern and decoration, such as those produced by the famed Gribelin family, but from the early 17th century, glittering enamelled watch cases in luminous colours came into fashion. The watch cases were enamelled using both 'champlévé', a technique dating back to medieval times in which indentations carved out in the metal are filled with coloured enamel, and by painting the enamel directly onto the metal in delicate strokes using fine brushes and needles. The goldsmiths Jean Toutin (1578 – 1644) and his son Henri (1614 – 83), who trained in Blois, were masters of painted enamel, producing elaborate enamelled cases for both watches and miniature portraits throughout the 1620s and 1630s. Other makers such as Louis Vautyer (1581 – 1638) adopted these techniques too, satisfying growing demand amongst the elites.

Seventeenth-century Blois goldsmiths and watchmakers kept close links with Geneva, London and Paris, where specialist case makers and decorators worked. Watch cases were decorated with flowers inspired by prints, or allegorical figures and occasionally with portraits.

In London, Huguenot refugee craftsmen fleeing upheavals abroad brought with them not only specialised skills for setting gems and cutting diamonds but also knowledge of the latest fashions in embellished watch cases. Huguenot designers published designs for goldsmiths' work in Paris, Blois and Lyon which were then exported to makers across the continent. Over 26,000 of these designs are now housed at the V&A.

Enamel portrait miniatures

As well as decorative cases, Huguenot enamellers used their skills to produce miniature portraits. The earliest enamel miniatures include a portrait of Charles I by Henri Toutin, a master of the technique, dated 1636. Toutin's miniature of Venetia Stanley, Lady Digby (1604 – 33), painted after she died, is based on a watercolour by the Huguenot London-based artist Peter Oliver (1589 – 1647). The bats' wings and extinguished torches on the frame of the miniature symbolise her death, while an inscription on the reverse refers to her husband's grief: "He tries to snatch a ghost from the funeral pyre and fights a battle with death, exhausting the skills of the artists. Everywhere he searches for thee – O, the bitterness of it". These enamel miniatures were ideally suited for remembrance pieces, as, unlike oil paint, the enamel colours do not fade, and remain just as vibrant today.

Royal miniatures framed with diamonds were presented by the French King, Louis XIV, to favoured foreign ambassadors as a demonstration of French craftsmanship. Later, these portraits were often re-mounted and the diamonds recycled into fashionable new jewels, so diamond-framed portrait miniatures are rare survivals today. One example, based on the French models, is now in the V&A collections. Made in Dusseldorf in around 1690, it shows an unidentified German Elector (a ruler of a German principality) and is typical of objects exchanged as diplomatic gifts.

Jean Petitot was one of the most celebrated artists producing enamelled portraits during this time. He worked at the English court from 1639 – 43, where he discovered 'carnation' – flesh-coloured pigment which gave his portraits a life-like luminosity. Petitot fled to France during the English Civil War, becoming enameller to Louis XIV, before moving to Geneva in 1687, aged 83. Geneva was a centre of the Protestant faith, and had become a haven for Huguenot watchmakers from 1550. Here, Petitot encouraged the production of enamelled cases for the flourishing export trade in watches. When he died in 1691 he was recognised as the greatest 17th-century miniaturist working in enamels – his career spanned seven decades.

Both Jean Petitot and his eldest son, Jean Louis Petitot (1653 – 1702), who trained in London, produced self-portraits as a marketing tool, to demonstrate their skills in this highly sophisticated artform. In 1728, their descendant, Francis Petitot, bequeathed "all my pictures in enamel and 'miniatures'" to his brother, Stephen. Huguenot families often bequeathed these small portraits as heirlooms or distributed them to friends as mementoes. In the 19th century, enamels by the Petitot family remained highly sought after among collectors. The tailor John Jones assembled a large collection of portrait miniatures of English and French courtiers by Petitot, which he later bequeathed to the V&A. Unlike watercolours, enamel portraits do not fade when exposed to light and can be permanently displayed.

Also from a Huguenot family, the Swedish-born enameller Charles Boit (1662 – 1727), painted royal and political portraits intended for both gift or display. These objects were commissioned by courtiers and members of the royal family to nurture and demonstrate loyalty. In London in 1696, Boit was appointed court artist to William III and then to Queen Anne. His brilliant large double portrait of Queen Anne with Prince George of Denmark was probably painted from life. Boit was paid an advance of £1,000 by Prince George to paint a large-scale enamel in celebration of the 1704 victory at Blenheim. Unable to complete this technical challenge however, Boit was forced to leave London. He was appointed professor at the French Royal Academy of Painting, despite his Protestant faith.

Art schools founded in Geneva, Switzerland, ensured a steady flow of talent to meet European demand for portrait miniatures. Jean André Rouquet (1701 – 58) trained in Geneva before working in London. There in the 1740s he painted a portrait of William Pitt, Earl of Chatham, later Minister in Charge of the Seven Years War in Europe.

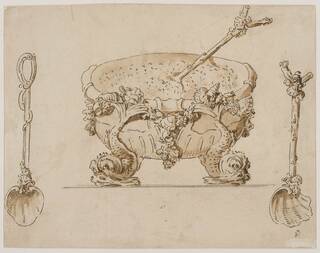

Gold snuff boxes

Gold snuff boxes were also decorated with enamels. In Berlin, Frederick the Great, King of Prussia, encouraged local goldsmiths to emulate French fashion. Daniel Baudesson (1716 – 1801) and Philipp and Samuel Colliveaux (working 1740 – 60) were of Huguenot descent. As Frederick the Great's court goldsmith from 1766, Baudesson produced 18 enamelled gold snuff boxes. An oval box in gold marked by Baudesson is painted in enamel with a scene of 'Minerva as Patron of the Arts and Science'. The enamelling is probably by Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki (1726 – 1801) who created this spectacular object using a number of skilled techniques – painting highly detailed scenes in enamel using fine brushstrokes, framing each scene with an undulating design of tree branches and leaves in translucent enamel over engraved gold, and contrasting the smoothness of this enamel with an intricate engraved pattern on the gold backdrop, using a mechanical process known as guilloché.

Enamelled watch cases remained fashionable, but with the classical revival in the later 18th century, colours were limited and allegorical subjects were often painted in 'grisaille' (monochrome). A watch case signed 'AT' demonstrates the skill of Augustin Toussaint, apprenticed from 1768 to George Michael Moser. Moser had made his name as a chaser, producing patterns and designs on watch cases by engraving into the metal, but he turned increasingly to using enamelling as a means of ornamentation and embellishment, becoming a master of the art form.

From 1767 to 1772, Augustin's father, Louis, worked with James Morisset (1738 – 1815) in London, where they supplied small enamels to retailing goldsmiths Parker & Wakelin. Morisset continued until 1800, specialising in gold and enamelled presentation boxes and dress swords. This example was presented to Lieutenant Colonel James Hartley by the Honourable East India Company for saving the army from annihilation during the First Maratha War (1775 –82).

Also based in London was James Tregent (active 1770 – 1804), watchmaker to the Prince of Wales, later George IV, and his brother Anthony who specialised in making and retailing enamelled calendar snuffboxes. Intended as New Year gifts, these trinkets were sold at the fashionable toy shops including that run by the Huguenot Thomas Harrache in London's Pall Mall.

Fleeing religious persecution, these networks of Huguenot refugees revolutionised goldsmithing and metalworking across Europe. Bringing with them their knowledge of sophisticated techniques and fashionable designs, their legacies are seen in the wealth of precious objects bearing Huguenot names in our collections today.