Legendary French couturier Pierre Balmain (1914 – 82) spent his early years working in wartime Paris alongside fellow up-and-coming designer Christian Dior. This extract from his 1964 autobiography describes the 'Birth of Balmain', his very first fashion show.

For that first collection I had a staff of 24. Today the house of Balmain employs about 600, 450 in the making and sale of model dresses, and 150 for the boutique. These figures do not take into account, of course, the employees of the factories which make Balmain jerseys, scarves, etc.

I congratulated myself that the drawing-room where the showing was to take place had been decorated in admirable taste. The walls were painted in aquamarine blue with white mouldings, and the ceiling of angels imprisoned in oval frames had been painted about 1890 by a Princesse de Broglie, whose family still owned the house. The curtains were of white mercerised linen (a textile finishing treatment which improves strength) and I had had reproductions of 18th-century chairs made at Aix-les-Bains.

This was the setting in which we worked. Mother supervised the last installations, brandishing a folding rule which she kept on breaking. I worked with my charge-hands often far into the night. Aunt Louise came to help us and I gave her the job of cutting out some pill-box hats in Persian lamb – the only hats in the collection. And one evening I, who knew nothing of sewing machines, had to get down to padding the lining of a cape.

We worked that time in what is probably the popular conception of the way fashion collections are prepared: frenziedly, with people fainting, and staff having to be plied with black coffee to keep them going. I had taken rooms in a hotel opposite the building, but Aunt Louise, Juliette the charge-hand, and myself worked right through that night before the great day. And when the heads of the needlewomen began to nod dangerously we let them sleep on the carpet but with our magnificent rolls of material for pillows. We were all very enthusiastic, very excited and inspired by a passionate belief that we were going to be a great success.

In every way the circumstances of that first showing seemed to be as full of drama – or melodrama – as a second-rate film. Even my opening date, which I had fixed for 12 October 1945.

I had taken great pains to avoid clashing with that of any other Paris couturier. Then I heard to my horror that Madame Grès, who had one of the most distinguished houses in Paris and was supposed to be showing a week beforehand, had changed her date to 12 October. As a virtual unknown, I knew I could not hope to compete for an audience on that day with Madame Grès.

My immediate reaction was that she had made the change on purpose to thwart me, although I should have realised that she would not know I existed. Seething with fury, I picked up the telephone and asked to speak to Madame Grès personally.

"Madame," I told her, "I am a beginner, and I have no money. I have sent out my invitations and I cannot afford to send telegrams everywhere to cancel them. You were supposed to have your showing last week: could you possibly select another date?"

"Of course," she said at once.

I shall never forget that generous gesture. Madame Grès, one of the great ladies of the Paris fashion world, had readily altered her own arrangements to help an unknown designer. Her consideration helped me not only in a practical way, but also bolstered my self-confidence. If I could be the object of the trust which the landlord had put in me, and the kindness of Madame Grès, then there was no doubt that destiny was on my side!

But there was still another battle to win. The very morning of my opening, as I was arranging the last details and setting out the chairs, a police officer and two gendarmes entered with a bailiff who presented me with official notice to quit the apartment within three days. I was so tense and wound up that I just exploded.

"Get out!" I screamed. "Get out!"

I am surprised that there were no repercussions for the officer was a Colonel of the Gendarmerie, an elderly, important man. But he must have understood how I was feeling on that day, for they left without a word. Later, when another government official turned up with a further eviction order, I seized him by his lapels and pushed him through the door. And finally, after many uneasy months, I received official confirmation that I could remain where I was: the house had been de-requisitioned, and for this, the landlords were very grateful to me.

When the police and the bailiff had gone, I finished arranging the seating, settled last-minute problems with the mannequins – and the guests for my first press showing began to arrive. Among those coming to give me moral support were my old friends from Aix, Gertrude Stein and Alice Toklas. They brought with them their big white French poodle, Basket, and a tall Englishman whom I had never seen before: Cecil Beaton. I placed them in the middle of the front row.

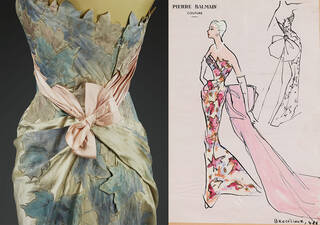

I had only about 45 or 50 models to show, but they were enthusiastically received, mainly, I think, because they struck a new note of freshness and luxury in those austere days just after the war. I had based the whole collection on the theme of luxury combined with simplicity, and a slight touch of the East.

I opened with a mannequin wearing a pair of grey flannel slacks, low-heeled brown suede shoes, and a loose brown homespun jacket like that of a Breton sailor. With her, on a lead, was my own pet Airedale, Sandra.

What followed was inevitable. Sandra saw Gertrude Stein's poodle at the same moment that Basket saw the Airedale. There was a furious battle, before Gertrude, myself, the mannequin and some of the salesgirls succeeded in separating the dogs. But the dog-fight had caused amusement and set a note of informality which probably helped the show get off to a good start.

As I have said, there was an oriental flavour about many of the models: large woollen kimonos, fastened with a zip at the shoulders so that no one could see how the mannequins had got into them, and worn with embroidered necklaces of multicoloured pearls, or trimmed with black Persian lamb which had been cut in strips from one of Mother's fur coats.

The most expensive garment – at the then astronomical price of 120,000 francs, which is the equivalent of about £1,500 today – was a dinner dress of white brocade, embroidered all over with silver and pearls. We never sold it, but it was a spectacular item which gained plenty of publicity in the press next day. The last dress – a white and silver bridal robe – brought an outburst of applause which made me realise that my worries were over, at least for the moment. My first show was a success.

The complete My Years and Seasons is now available in the V&A Fashion Perspectives e-book series from online retailers.