Louis Comfort Tiffany

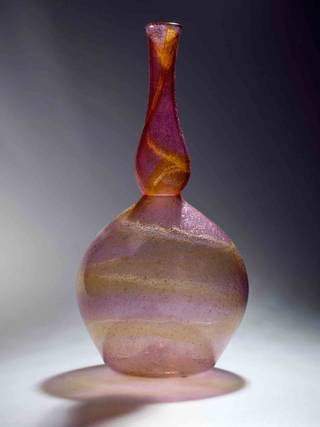

An American creator of luxury objects ranging from stained glass to jewellery, Louis Comfort Tiffany began his career as an artist but swiftly turned his attention to the decorative arts. With Arthur Nash, a glassmaker from Stourbridge, England, Tiffany developed a method for blending different colours of glass in the molten state. The two experimented with treating the glass with metallic oxides and exposing it to acid fumes to achieve lustrous effects. Tiffany named the blown glass from his furnaces Favrile, from the Old English word 'fabrile' meaning handmade.

Tiffany's experimental and unconventional use of glass, including his opalescent and marble-like forms can be seen in the vases and bowls in our collection. Swirling, feathery patterns create a languorous ripple effect across their exteriors. Tiffany became enormously successful using these techniques, and although his metallic iridescent glasswork is wholly unique, it inspired many imitators.

Lötz Witwe Glassworks

In 1897, the owner of the Johann Lötz Witwe Glassworks, Max Ritter von Spaun, admired an exhibition of Tiffany Favrile glass exhibited in Bohemia and Vienna. He became convinced that Lötz should adopt this new Art Nouveau style. Although the company began by copying Tiffany's iridescent glass, they soon evolved their style and technique, creating lustrous, wavy effects of their own. This new style was given the name 'Phänomen' glass and was exhibited alongside Tiffany, Gallé, Daum and Lobmeyr at the Paris Exposition Universelle in 1900, eventually winning a Grand Prix.

Emile Gallé

French designer Emile Gallé of the Ecole de Nancy, was a master of glasswork. His glassmaking and artistic style was highly influential on other Art Nouveau artists of the time, including the Daum brothers. Gallé's background in botany and his interest in Japanese design combined to govern his aesthetic. Two pieces – a vase and bowl – shown at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1900, were bought by the V&A at the time (for £13 and £19 respectively) from a special fund put aside for the purpose of bringing such objects to a UK audience.

Gallé's art is characterised by his interest in symbolism, especially of the more morbid and introspective type. The chrysanthemums in the decoration on the vase would not have been used lightly, carrying both their Japanese significance as an Imperial flower and their French association with funerals and death.

The bowl imitates the appearance of water lilies floating on mossy, reflecting waters. The flowers are applied and separately carved, while the bowl's surface is fluted in spirals. The glass type, known as 'dichroic', changes appearance with different lighting angles, an effect created by the inclusion of minute gold particles.

The Oakleaf vase was one of Gallé's favourite designs. He felt a deep affinity with the forest throughout his life. His furniture was made of many woods, each of which held particular meaning for him. The doors to the Gallé factory were in carved oak and carried his personal motto 'Ma racine est au fond des bois' (My roots are in the depth of the woods). Oak has clear associations with re-birth each spring, and strength and longevity. Colour too was important, and the greens of this vase invoke the dappled light of the deep forest. A number of versions were made, both fire-polished as here and other examples which leave the marks of the carver's tools unsmoothed.

Chistopher Dresser

Designed by Scottish glassmaker Christopher Dresser, this 'Clutha' glass has a distinctive bubbled and streaked quality. Named after a Roman river god, its daring colours and metallic streaks or foils are meant to imitate the effects of Roman and Venetian glass. Along with recently excavated Roman archaeology, Dresser was also inspired by Japanese art that had flooded into the West after trading rights were established with Japan in the 1860s. Dresser's glass was sold exclusively through the avant-garde London shop Liberty's, founded by Arthur Lasenby Liberty as an emporium importing goods from Asia. Soon Liberty's was pioneering its own version of Art Nouveau, known as Stile Liberty.

Jewellery

The V&A's jewellery collection houses some of the finest examples of Art Nouveau craftsmanship, including pieces by René Lalique, Georges Fouquet and Philippe Wolfers.

René Lalique

René Lalique was Art Nouveau's most important jeweller. He developed a new stylistic language based on sinuous interpretations of natural forms, and championed non-precious materials such as enamel, glass and horn. The resulting pieces were both dramatic and ethereal, and had a profound influence on other jewellers who went on to work in the Art Nouveau style.

Lalique completed an apprenticeship and later attended art school in England before working as a designer for well known Parisian jewellery firms. During the 1890s he undertook an exhaustive programme of technical research into glass and enamel, which led to his distinctive jewellery style. Made in about 1895, this brooch shows Lalique's developing interest in stylised motifs from nature. He tended to distance himself from conventional precious stones – however this piece was designed for Tiffany & Co. and perhaps as a result is realised in diamonds.

The Art Nouveau style caused a dramatic shift in jewellery design, reaching a peak around 1900 when it triumphed at the Paris Exposition Universelle. Lalique was known as 'the admitted king of Paris fashions', and chose his materials for aesthetic effect and artistic refinement, not for mere preciousness or brilliance. Credited with introducing horn into the jewellery repertoire, he dazzled the public with a collection of ornamental combs made of horn. They were moulded and sculpted in the shape of flowers, waves and butterflies.

Lalique's iris buckle demonstrates his mastery of silver. Irises were one of the most persistent motifs in Japanese art and this buckle is a fine example of the influence of Japan on Art Nouveau design. Lalique's irises are not only decorative but also give the piece its outline, which is created by extending the long leaves above the flowers and curling them over into a continuous line.

In 1905 Lalique partnered with perfumer François Coty and began to design glass bottles and vases. For the next forty years, Lalique would become a master of crystal and glass and transform from an Art Nouveau jeweller to an Art Deco glass pioneer.

Philippe Wolfers

Philippe Wolfers was the most prestigious of the Art Nouveau jewellers working in Brussels. Like his Parisian contemporary René Lalique, he was greatly influenced by the natural world. Similar to Lalique, Wolfers' pieces were less about gemstones and more about enamel, including plique-à-jour enamel. French for 'letting in daylight', plique-à-jour enamel is translucent, allows light to pass through and is backless, or not fused to a base. Enamelling in this manner is technically difficult to master, making Wolfers' designs even more impressive. Exotic orchids, like the one used for this hair ornament, were a symbol of the Art Nouveau movement and its practitioners' fascination with nature, sensuality and exotic flowers.

Liberty's Cymric Jewellery

Established in 1875, Liberty's department store in London built its reputation on supplying artistic and unusual products. In 1899 it launched a line of 'Cymric' jewellery, which drew on both the Art Nouveau and Arts and Crafts styles. Cymric jewellery featured sinuous lines, unusual gemstones and often appeared to be hand-beaten.

Cymric jewellery was very popular. Its success was partly due to the innovation and talent of the designers and silversmiths employed by Liberty, including Archibald Knox and Oliver Baker. Knox was a designer and teacher from the Isle of Man, and was responsible for some of the Cymric range's most exceptional designs, particularly those based on Celtic interlace. Baker was a painter and designer from Birmingham whose metalwork was highly prized by Liberty.

Eugène Feuillâtre

No jewellery collection would be complete without a tray upon which to place those jewels. This ring-tray is the work of Eugène Feuillâtre, a distinguished Parisian enameller who frequently exhibited his work at the Paris Salon. Feuillâtre mastered the backless plique-à-jour technique, which required considerable skill. Covering such a large area, the enamel on this dish is a tremendous achievement. The plique-à-jour is mounted in silver in the form of three branches that rise from a foliated base. There is a silver edge to the enamel, which represents an underwater scene with fishes.