A key means by which Palladio's ideas spread was through his 1570 publication I quattro libri dell'architettura (The Four Books of Architecture), a treatise on architecture that contained illustrations and descriptions of his own architecture, together with the Roman buildings that he admired.

Palladianism first emerged in Britain in the work of the Scottish architect Colen Campbell (1676 – 1729). His book Vitruvius Britannicus, or The British Architect (1715) was a catalogue of contemporary British buildings. It featured a design for his pioneering house at Wanstead, Essex, which incorporated all the key Palladian features: a focus on symmetry, proportion and balance, with one side of the building a mirror image of the other; the use of temple fronts (a pediment supported by Corinthian columns or pilasters) and large tripartite Venetian windows. It also featured a rusticated basement – a lower floor which contained masonry blocks with a rough, rustic appearance that contrasted with the smooth finish of the building at a higher level. Above all, the composition relied for its effect on the careful balance between the blank, untextured wall surface and the window openings, giving it a sense of combined grandeur and repose.

It would be another 15 years though before a similar great Palladian house was to be designed in Britain. In that time Palladianism acquired a much more persuasive champion – the architect Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington (1694 – 1753).

Lord Burlington had studied the buildings of Andrea Palladio at first-hand in Italy and had a collection of designs by both him and the 17th century architect, Inigo Jones (1573 – 1652), who was also a keen admirer of Palladio. Burlington was an enthusiastic promoter of Palladianism (he had sponsored the English translation of Palladio's The Four Books of Architecture) and from combining Italian and Jonesian sources, he formed a classically correct style that was uniquely British. It was as applicable to the smallest terraced house as it was to the grandest mansion, setting the pattern for British architecture for the next 100 years. For Burlington's followers, Palladianism also had a special meaning, signalling a link between the virtues and power of ancient Rome and the culture of Italy, and the culture, political systems and power of the burgeoning British nation.

Burlington's own designs were mainly for small buildings, the most characteristic being the extension to his own house at Chiswick in London. Begun in 1725, it was based partly on Palladio's Villa Rotonda at Vicenza, Italy.

As with many Palladian buildings, the plain exterior contrasted with its richly decorated interiors. These were not based on Palladio's own designs, but on details taken from ancient Roman buildings that were combined with fireplaces, ceilings and other details taken from Inigo Jones. While the walls of most of the rooms were hung with woven textiles, the central saloon was plastered, painted and decorated with sober sculptural ornament, a pioneering and highly influential concept.

The interior of Chiswick House was designed by Burlington's assistant and protégé, William Kent (1685 – 1748), who was also responsible for designing furniture and other items for subsequent Palladian interiors. Again, there were no examples provided by Palladio, so Kent, who was trained as a painter but had a brilliant and poetic imagination in a number of design fields, devised new models derived equally from Italian Baroque examples and ancient Roman sculptural ideas.

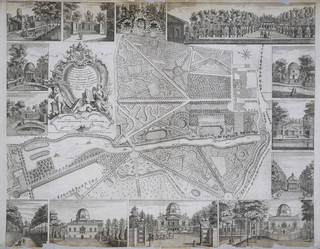

Palladian buildings were intimately linked to the gardens that surrounded them. At first, gardens (like those at Lord Burlington's villa at Chiswick), filled with small classical buildings and complicated paths, were designed to recall the gardens described in the great literary works of classical antiquity. As no examples of these ancient gardens survived, the models used were often taken from more recent Italian examples. These gardens, marked by their asymmetry, were in marked contrast to the grand symmetrical gardens of the Baroque period, aligning them instead with a trend towards the natural in British gardening, which began about 1700.