The theatre and the Baroque

The Baroque theatre was the setting for magnificent productions of drama, ballet and also opera, which was a new art form at the time. It was popular both with the public and at court, where members of the royal family and nobility often took part. A Baroque performance combined impressive illusionistic sets and luxurious looking costumes with texts and music to create marvellous spectacles.

The V&A's collection includes a rare surviving Baroque theatrical costume. It comes from a private theatre in Meleto Castle, Tuscany in Italy. A very early example of a costume made especially for the stage, it was probably also used for other entertainments such as dancing. Inside the candlelit theatre, this costume's metallic thread and glass 'jewels' would have shone and sparkled in the flickering light. The costume is built on hessian, a woven fabric, to provide strength but there is also evidence of fine craftsmanship, such as in the gold metal stitching – almost certainly the work of professional embroiderers. Its short length is typical of the fashion for the so-called 'Roman habit' for male costumes, which were intended to convey a dignity appropriate for tragic and noble figures. Female characters, meanwhile, tended to be costumed in rich, full length, contemporary fashionable dress.

Theatre provided ruling elites with the means of fashioning their own identity and establishing their reputation. Easily adaptable, and with the capacity to captivate audiences, performances were staged to mark key occasions.

In France, music and theatre became a key element of the presentation and public image of King Louis XIV (reigned 1643 – 1715). Following the Fronde, a series of civil wars between 1648 and 1653 where Louis faced the opposition of various factions, including the nobility, theatre provided a means for him to assert control and indulge in propaganda that would ensure a rebellion would not happen again.

Our collection includes a pen and ink design by Jean-Louis Berain for the costume of the Roman god and hero Hercules, who appears in Atys, written by Jean-Baptiste Lully for the court of Louis XIV. Atys was an example of a tragédie en musique, a type of early French opera. It was so popular with the King that it became known as 'the King's opera'. The design shows Hercules in a ballet pose wearing a Roman-style costume, with his identifying club and lion skin.

Atys was first performed in 1676 to the French court and later that year to the Parisian paying public. Hercules appears as a dancer in the prologue to the main part of the opera – as important as the opera itself, as it openly praised the king and helped to construct the mythologies around him.

Baroque and opera

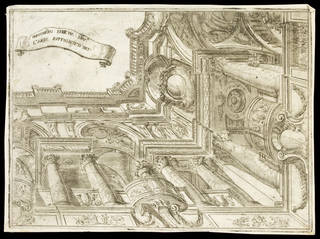

It was Italy, however, that saw the birth of opera. From there, it spread to the rest of Europe, where it took hold as the predominant genre of theatrical performance during the second half of the 17th century. With its fusion of music, poetry, painting, lighting and engineering, opera can be seen as the archetypal Baroque art form. Illusionistic stage sets were developed with machinery that meant that they could be changed within a few seconds in front of the audience – all part of the spectacle. Machines also provided sound effects, such as thunder, even lighting. There was a Europe-wide wave of theatre construction as proof of courtly or civic power, and these new buildings established the theatre types we know today. The buildings reached new levels of sophistication towards the end of the 17th century and in first half of the 18th – principally as a result of the influence of the Galli Bibiena dynasty. Brothers Francesco and Ferdinando Galli Bibiena established their reputation by producing stage sets for a number of theatres across Italy. However, it was Francesco's 1699 commission to renovate the theatre in Hofburg, Vienna that paved the way for his family's success across Europe. He created a prominent two-storey imperial box, which made the ruler into an elevated and privileged spectator and, for the audience, offered an alternative focus to the stage.

A significant and enduring theatrical innovation was the 'angled scene' or scena per angelo, credited to Ferdinando. First used in Bologna, Italy, in 1703, it meant that, rather than having a centralised perspective, more of the spectators could enjoy the stage illusion.

The Baroque square

The Baroque era saw the creation of great city squares with architecture, statues and fountains used to present an impressive, unified whole, as seen in the likes of Place Louis-le-Grand (now Place Vendôme) in Paris and Piazza Navona in Rome.

Such urban squares hosted public celebrations of national and international importance, held to mark events such as coronations, state funerals, major military victories, royal births, birthdays and marriages. These festive occasions ranged from processions to firework displays and public theatricals to tournaments and grand equestrian carousels.

The diarist John Evelyn noted the spectacle that marked the entry of Charles II into London on 29 May 1660 after his exile during the English Civil War. As well as 20,000 on "horse & foote", Evelyn describes flowers, bells, streets hung with tapestries, fountains running with wine: a celebration that lasted from 2pm to 9pm. What he recalls is by no means unusual for such occasions. Buildings would be adorned with textiles, hangings and pictures, while roads were laid with flowers, straw and gravel and enhanced with purpose-built, temporary structures. These creations would bring together artists, designers and technical experts. The Flemish artist Rubens, for example, was commissioned to produce temporary props and apparatus for such occasions. While the overall effect was one of magnificence, many of the props were made from the likes of canvas, wood and plaster that were painted to look like more expensive materials.

During processions, the finely dressed participants – which could include royalty – would move through the city, stopping at significant symbolic locations, marked by such purpose built structures. These processions shaped how both participants and observers experienced their urban environment and specific landmarks would be highlighted to reinforce the point of view being put on display.

Impressive firework displays were often staged as part of such celebrations. John Evelyn estimated that over 200,000 people gathered to watch a fireworks display marking the signing of the peace treaties collectively known as the 'Peace of Rijswijk' in London's Piccadilly in November 1687. Such high profile performances were powerful ways in which to convey messages to large numbers of people from all social classes.