Royalty and loyalty

The lives of monarchs and their courtiers were far removed from those of ordinary citizens and were common topics of conversation and gossip. Commemorative ceramics were produced to satisfy public interest, often to mark coronations, royal marriages and deaths. In some cases, pieces were produced long after the subject's lifetime, and ownership could signify loyalty to, or belief in, a particular cause or political movement.

King Charles I was one of the first monarchs to appear figuratively on British ceramics. The impressive tin-glazed earthenware dish showing Charles I and his heirs Prince Charles, Prince James and Henry, Duke of Gloucester, was produced in London in 1653, four years after his execution, when England was governed by a republic. It demonstrates that people with Royalist sympathies – probably local merchants in London – were purchasing ceramics to signify their loyalty to a king, at a particularly dangerous time to do so. However, it was the Restoration of Charles II in 1660 that led to a huge rise in popular commemorative ceramics. From this date many pieces of simple domestic pottery, such as beer mugs, were decorated with depictions of Charles II, and would be used for drinking to the health of the newly restored King.

Although fewer commemorative ceramics are produced in periods when public approval in the monarchy wanes, the tradition of commemorating royal events on ceramics continues. If you visit the museum's British Galleries you can find a mug made to celebrate the marriage of Prince Charles (now King Charles III) and Lady Diana Spencer in 1981, displayed alongside its 17th-century counterparts.

As well as providing cups for toasting and commemorating, the ceramics industry produced a vast number of vessels for tavern culture more broadly, encouraging drinking games for example, or simply designed to trick, surprise and delight. These novelty vessels are known as 'stirrup' cups as they were intended to hold 'one for the road', when a departing drinker had their feet in the stirrups. Rounded-bottomed cups can't be put down without spilling the contents, so they encouraged the drinker to finish in one go. The vessels that imitate potatoes may refer to 'potcheen' – a highly alcoholic drink distilled using potato starch.

'Balloonomania' and animal menageries

Huge public spectacles also became subject matter for decorating ceramics. In the late 18th century, excitement around balloon flight grew to an international 'mania', combining public spectacle with an interest in scientific advance. In 1784, the Italian Vincenzo Lunardi completed the first manned balloon flight in England. His appearance above the rooftops of London caused a sensation, with some newspapers reporting crowds of up to 200,000 and roads rendered impassable by onlookers. Not everyone was overcome by 'balloonomania' however. Samuel Johnson wrote to his friend, the artist Sir Joshua Reynolds: "I have three letters this day, all about the balloon, I could have been content with one. Do not write about the balloon, whatever else you may think proper to say".

Travelling exhibitions of animals, often known as menageries, were popular attractions in the 19th century. Audiences were enthralled by the perceived exoticism of animals like elephants, tigers, and bears, and thrilled by the danger associated with them. Britain's colonial expansion facilitated the trade in such creatures, with sailors sometimes supplementing their income by bringing animals back to Europe with them. One well-known menagerie owner was George Wombwell, who was said to have started his enterprise with two snakes purchased from a sailor at the Port of London. These travelling menageries were captured in all their colour and eccentricity in Staffordshire pottery of the 1830s.

Celebrities: famous and infamous

The 18th and 19th centuries were golden years for entertainment in Britain and the building of theatres gave rise to some of the first 'celebrity' actors. Chief among them were David Garrick, who wowed audiences with his naturalistic acting style; Sarah Siddons, who was famed for her tragic performances, and William Henry West Betty, who had crowds flocking to catch a glimpse of him at the age of 13.

The theatre was one of few places where all classes of society came together (although in different seats), and popular actors became ripe for reproducing on ceramics. David Garrick was immortalised in a 1745 painting by William Hogarth (1697 – 1764), depicting him as Shakespeare's tormented Richard III in his tent before the Battle of Bosworth. Prints based on the painting in turn inspired a highly reproduced ceramic model that was made long after Garrick's death, reflecting his enduring celebrity status.

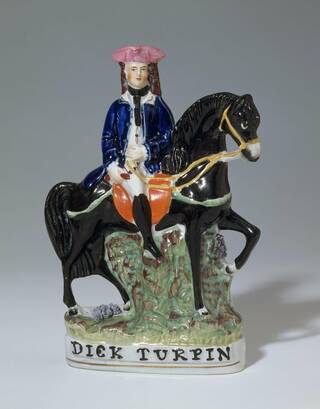

Ceramics were used to represent the infamous, as much as the famous – from the highwayman Dick Turpin, who became wildly popular through constant retellings of his exploits, to the pickpocket and socialite George Barrington, whose trials and tribulations were widely reported in the press.

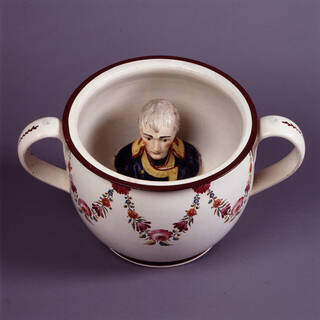

However there was possibly no more universally divisive figure in the 19th century than Napoleon Bonaparte (1769 – 1821). Considered by some a tyrant, and others a romantic hero, his success in the French Revolutionary Wars saw his rapid rise to power. Depictions of Napoleon in ceramic form vary wildly from dignified and regal portraits to biting satire. A bust in the V&A collection shows Napoleon looking stately in his lavish First Consul uniform. Made in England, it perhaps dates from around 1802, when Britain made peace with France through the Treaty of Amiens. More often than not a national enemy, Napoleon at this time may have been an acceptable subject for the British market. Yet only a few years later we see Napoleon's reputation literally flushed down the toilet. In the collection of Brighton Museum and Art Gallery, a bust of Napoleon similar to the V&A's has been placed inside a chamber pot. Its Latin inscription 'PEREAT' – meaning 'Let him perish' – encourages the user to relieve oneself on his head.

Popular pottery

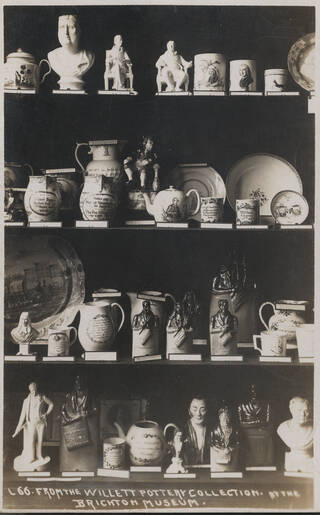

The South Kensington Museum (now the V&A), was collecting so-called popular pottery throughout the 19th century, although acquisitions of ceramics were generally made on the basis of rarity, manufacturer and technical process. Many of these popular objects, with the exception of some of the older and more unique pieces, were mass-produced due to their wide appeal, and would have been considered common. However, one collector saw the intrinsic value of these ceramics as social and cultural documents. Henry Willett (1823 – 1905), a Brighton-based brewer, formed a large collection of popular pottery that survives intact at Brighton Museum. He believed the most important aspect of ceramics was 'the greater human interest which each object presents', and sought to portray the history of Britain through its ceramic output. In 1899 the entirety of Willett's collection was displayed at the Bethnal Green Museum (now Young V&A), where it was considered appropriate subject matter for its high entertainment value.