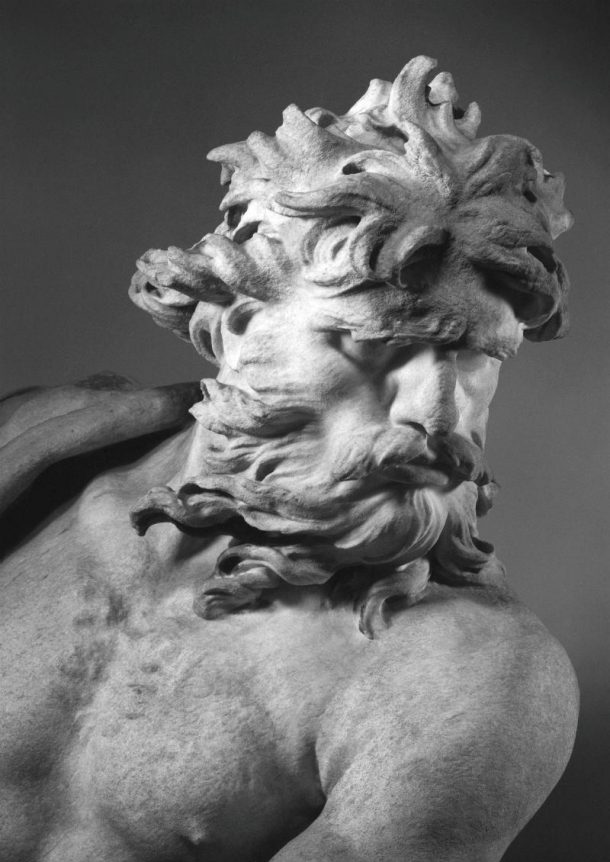

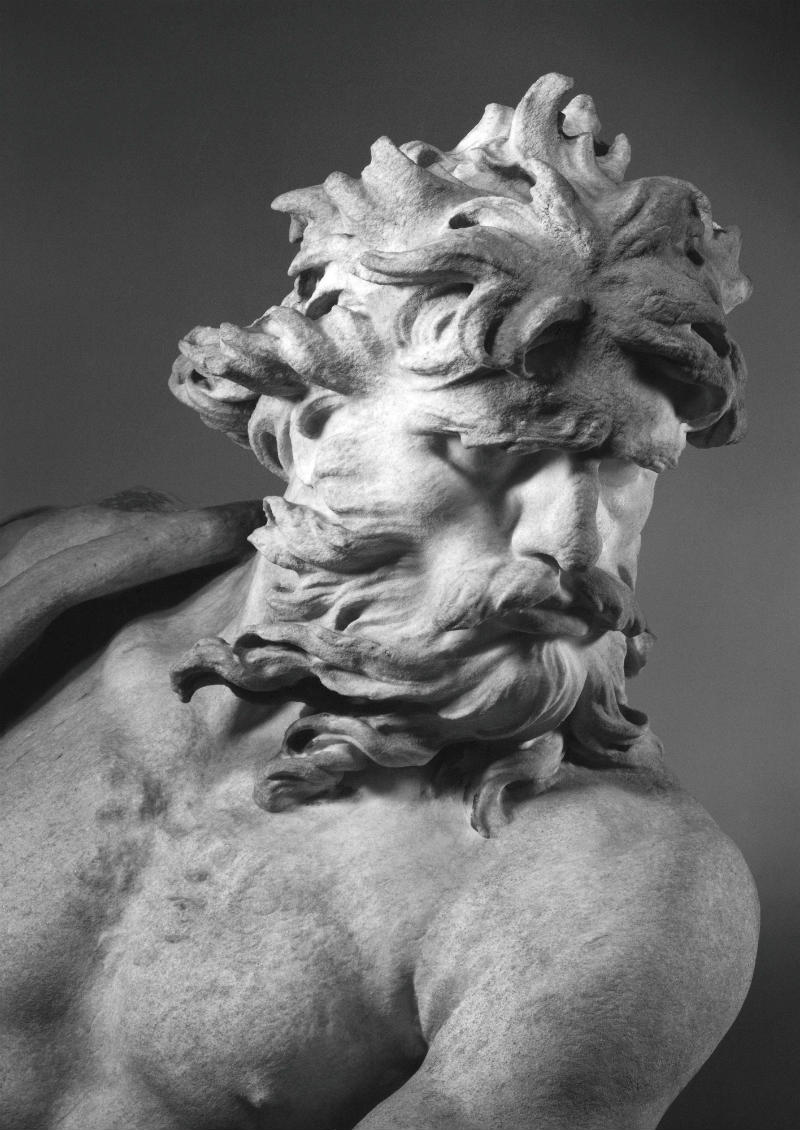

The Neptune and Triton (Mus. No. A.18-1950) by Gianlorenzo Bernini (1598-1680) is one of the V&A’s most well-known Italian marble groups. The sculpture, which stands nearly two meters high and weighs over 8oo kg was recently moved to the newly refurbished Europe 1600-1815 gallery, where it now stands in prime position, with Neptune casting his terrifying gaze upon whoever enters.

The original location of the marble group

The sculpture, which was carved in 1622-23, depicts the sea-god Neptune, and his son Triton, the merman, blowing a conch. It was created to serve as a fountain figure with other sculptures as part of a large fish pond in the garden of Villa Montalto in Rome, where it stood as part of a complex system of water features.

In 1786 it was sold to the renowned English painter Sir Joshua Reynolds, who kept it in his coach house. After Reynold’s death in 1792, the sculpture was acquired by Lord Yarborough, who housed it first in London then in Lincolnshire, where it remained until it was purchased by the V&A in 1950, with the assistance of The Art Fund and contributions from the John Webb and Valentin Bequest.

Its movement within the Museum

Since its arrival in the V&A, Neptune and Triton has been moved several times to various parts of the building. For many years it was displayed in a niche at the entrance to the Costume Court, known today as the Fashion Galleries, overlooking Gallery 21, where it could be seen in relation to Giambologna’s great marble group of Samson and the Philistine (A.7-1954), now in Gallery 50A of the Medieval & Renaissance Galleries near the grand entrance.

On 30 April 1980, it was moved to the then Raphael Cartoon Court, where it stood until it was transported in 1992 to the day-lit Gallery 50B.

When the Dorothy and Michael Hintze Galleries devoted to Sculpture in Britain were created in 2005, the sculpture was again on the move, but this time placed against the backdrop of the garden.

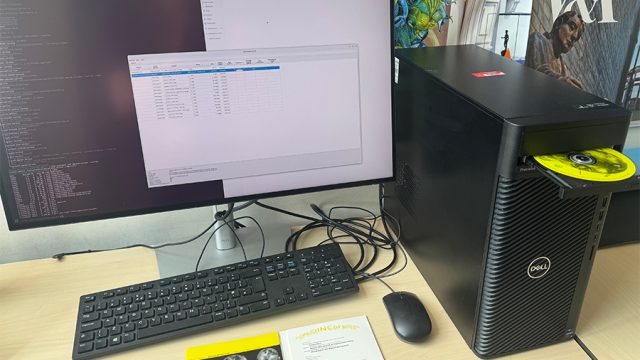

In mid-November 2015, the marble group started its journey to a new position in Gallery 7, in the newly-opened Europe 1600-1815, via the Sculpture Conservation studio, where it was fitted onto a new support.

Whether the refurbished Europe 1600-1815 gallery will be Neptune and Triton’s final destination is not known, but given its prime position in a space where there are fewer rival large sculptures, it seems to be an appropriate placement for this striking seafaring pair.

How large marble sculptures are moved in different locations in the Museum

Lifting and moving this solid, yet fragile, object was a carefully planned operation undertaken by the Museum’s experienced technical staff including Tony Ryan, John Dowling and Phil James, who all have memories of transporting the marble to different locations in the Museum.

Senior Sculpture Curator Peta Motture describes how she watched the sculpture being released from its brick-built plinth in the Raphael Gallery to move it to 50B.

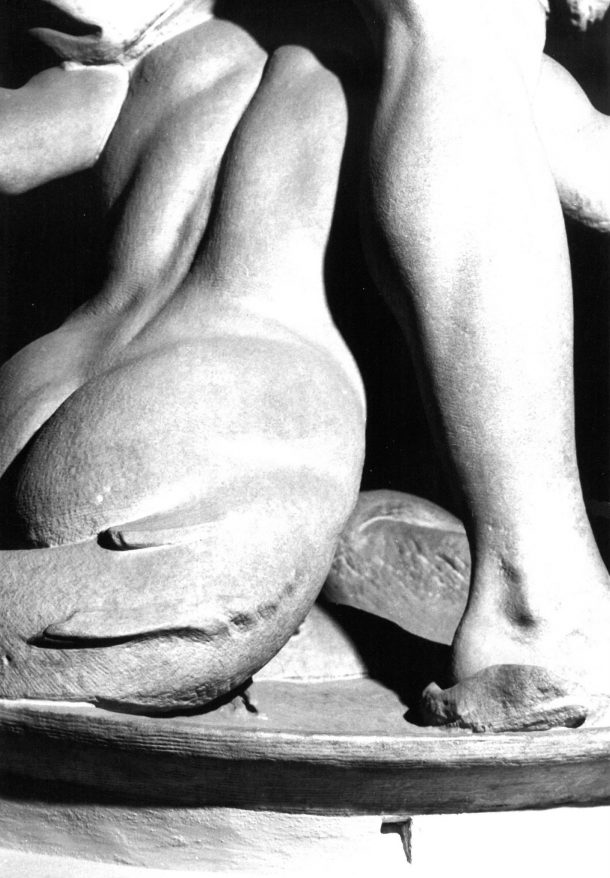

Its fragility meant that its weight could not be suspended from the slings, so a small team of conservators and technicians (including Tony and John) lifted the sculpture using four padded hydraulic wedges under the shell, all of which had to be raised at exactly the same rate. This allowed them enough room to put wedges underneath before lowering the sculpture onto slides to transfer it to a pallet for moving.

The sculpture can not rest on its base alone. Therefore some wooden wedges were left in place to stabilize it and to make it a little easier to move it in future, but every move brings its own issues.

Installation of Neptune and Triton in the Europe 1600-1815 Gallery was filmed by the Museum’s Digital Media Team.

Cleaning the marble

Once the marble stood firmly on its newly reconstructed plinth, my colleagues Vanessa Applebaum, Mariam Sonntag and I began cleaning the marble.

Naturally we worked from the top downwards with Vanessa and Mariam cleaning the highest points from a scaffold, while I was standing on a ladder, dusting the lower half of the figures.

We removed surface dust with soft brushes and vacuum suction. More ingrained dirt was removed with high absorption specialist sponges and purified water.

However, although the difference between clean and unclean was subtle, the water we rinsed off was surprisingly dirty.

Despite regular dusting, even in a comparatively clean museum environment, it is difficult entirely to eliminate dirt accumulating on the surface, particularly when the object is on open display. Managing dust is tricky and the V&A has devised a strategy to tackle dust particulate deposition on objects on open display. According to the V&A’s scientist Bhavesh Shah;

There are two types of fibrous particulates (from the objects themselves and from the visitors and their clothing) and non-fibrous airborne particulates (skin, soil, building dust, insect fragments, pollen, pollutants, etc). … the best way to preserve smaller scale objects on display is to place them inside well-built and well-sealed display cases.

However, this is obviously not appropriate for large-scale sculptures.

The Museum’s guideline on risks associated with dust :

When dust is allowed to settle it can accelerate biological, chemical and physical deterioration of objects. Dust can change the appearance of an object, detracting from the visitor’s experience. Shiny reflective surfaces become dull, and dark matt surfaces may become grey and flat. The size of the dust particle will determine how quickly it will accumulate; smaller particles generally take longer to settle and will travel further away from the source. Most dust will accumulate on horizontal planes and almost none on the verticals. Accumulations of dust can provide nutrients for fungal and pest/insect activity. In humid conditions dust may ‘cement’ onto objects that are hygroscopic meaning they attract moisture. If left for prolonged periods of time, certain types of dust may become ‘embedded’ between textile fibres and/or bonded to surfaces. Embedded dust particles can be abrasive and their removal may cause irreversible damage to the original surface.

Vanessa Applebaum, a student intern from the UCL Institute of Archaeology, describes her involvement with Neptune and Triton:

As a student, I have been introduced to many theoretical and technical practises of conservation; however, working on the scaffolding while cleaning Neptune and Triton was an entirely new experience. This particular treatment provided me with a different perspective—not only of the object, but also of the surrounding work that was being done in the new Europe gallery. Unlike treatment at a lab bench, there is an added intimacy and physicality when working closely with a large sculpture in situ, especially since I was focused on cleaning Neptune’s face, head, and upper body. The aerial view of the gallery space was an added bonus, as it gave me the opportunity to observe the creation and installation of Neptune and Triton’s new home.

Recurring cleaning regimes

Cleaning the surface brought back memories as I had carried a similar treatment ten years ago on the same sculpture when it was put on display in the Sculpture in Britain gallery. I spent a number of days working on the object, while changing groups of visitors stood beside me curious to know what I was doing.

I recall cleaning the surface meticulously, with stiff brushes and warm purified water. While rinsing the marble with clean water, I noticed foam with strong odour seeping out, which may have been residue of a type of alkaline soap, widely used in conservation in the 1970s. After finishing the cleaning, I used thick wads of cotton wool and tissue paper to absorb excess moisture from the surface. I also carried out some repair work on old discoloured fills under Neptune’s drapery.

Past treatments

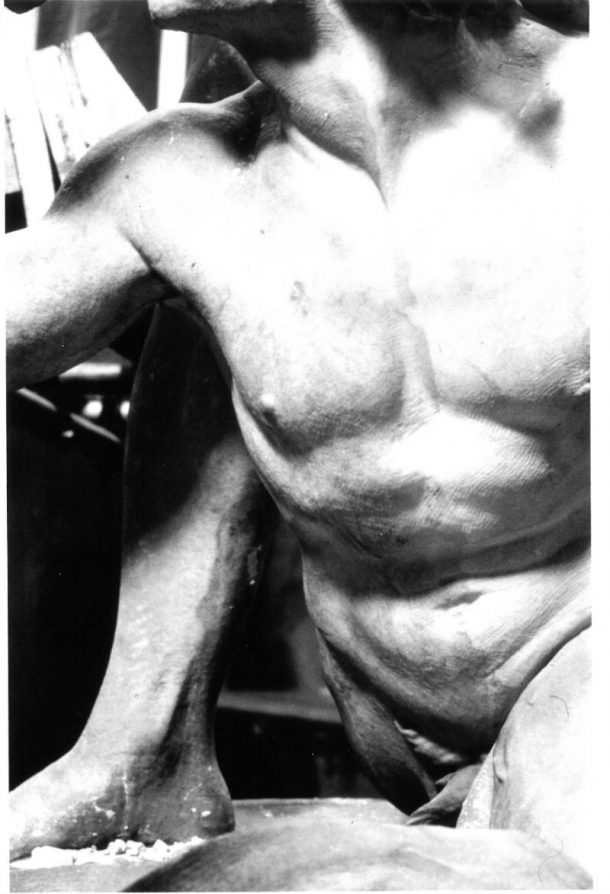

The sculpture had received a fairly extensive conservation treatment in 1979. In documents in the object files, conservators John Larson and Anne Brodrick described the condition of the marble as being considerably weathered, fragile, brittle and sugary, most likely due to the fact that the sculpture group had been outdoors for a significant length of time. In the outdoor environment it would have been subjected to fluctuating temperature (sunlight/heat, shade/cool and freeze/thaw) and humidity. Marble is made up of a network of crystals and so is less elastic than sandstone and limestone, the latter having clay structures which allow for some plasticity. The material expands and contracts which leads to a slow degradation of the stone which is also elevated by the presence of freezing moisture and/or salts. Particularly in combination with the deposition of acids and/or particulates that occur in the natural environment, these factors can have dramatic effects on a marble.

In the late 1970s there were networks of cracks visible on the surfaces of Neptune and Triton, old repairs had come loose, re-attached parts of the sculpture vibrated when gently tapped and the sculpture was at risk of suffering significant loss of detail or even fragmentary pieces of marble.

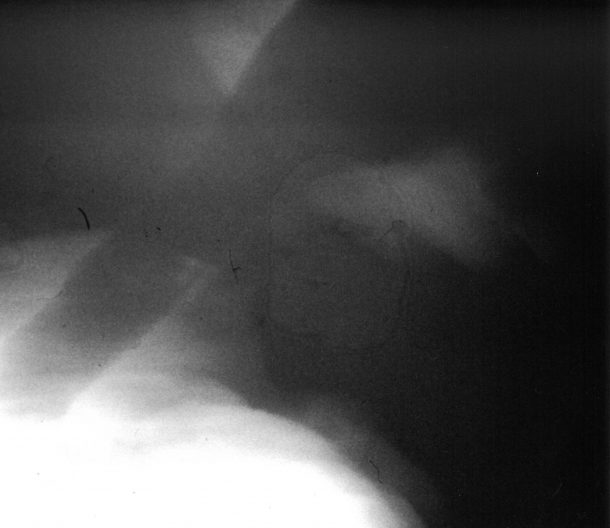

Radiography revealed an alarming porosity of the marble and many fine fissures running deep into the stone. The x-rays confirmed previous restorations: the left shoulder had been repaired, a large bent cramp attached the arm to the shoulder with lead at both ends inside the marble; the left forearm had previously been broken and had been repaired with a piece of round bar.

The conservators published an article titled ‘The Conservation of a Marble Group of Neptune and Triton by Gian Lorenzo Bernini’ (J.H.Larson, Case Studies in the Conservation of Stone and Wall Paintings, IIC 1986, pp.22-26) about the treatment which was very progressive for that time.

Another interesting aspect is that the sculpture was not hewn out of one block of marble as was common practice at the time. This was confirmed during treatment, when Neptune’s raised arm was painstakingly realigned into its proper positon. It became clear that Bernini had used a marble mortise and tenon joint to attach it to the torso. Bernini knew that a metal dowel would have corroded due to the high water content of the air around the fountain and as a result would have even fractured the stone. The two conservators were also able to undertake technical examinations around the sculpture’s function as part of the fountain itself.

Radiographs revealed lead tubes of about 3 cm diameter inside Triton, inserted into accurate shafts that had been made in the solid marble using simple hand-drills.

Larson’s publication amalgamated conservation and therefore resulted in a detailed understanding of the sculpture group.

To conclude

It has been a pleasure to work on such a prestigious object as Bernini’s Neptune and Triton. Though this is not the full story, it provides a flavour of how the sculpture has been moved and reinterpreted over the years. It seems that every move demands new thinking, and some conservation. The skill of the V&A’s highly experienced technicians enabled the sculpture to be transported safely from one gallery to another. We look forward to hearing the reactions of the visitors when they enter the gallery and walk around Bernini’s masterpiece.

I would like to offer my sincerest thanks to Mariam Sonntag, Vanessa Applebaum, Phil James and Peta Motture who contributed to this blog. I would also like to thank Richard Davis, Anthony Ryan, Cherry Palmer, Bhavesh Shah, Charlotte Hubbard, Simon Goss and Peter Kelleher.

Did you remove the metal bars from the sculpture??? Or did you leave inside??

This was really interesting to read about. I am interested in the new plinth and how and why it was chosen? Is it one block or built up of blocks? of what material?. My husband is a sculptor and is always keen to explore new ideas for plinths. Many thanks