This is the first of two blog posts which will discuss the 3D scanning of 25 objects in the museum’s collection as part of the wider exploration of digital reproductions during the Cast Courts FuturePlan project. The first will discuss why we undertook this project , and the second will discuss the practicalities of scanning such a complicated group of objects. For more information about the history of the Cast Courts please click here.

On 1 December 2018 the Cast Courts re-opened to the public, complete with a new interpretation space, The Chitra Sethia Nirmal Gallery, between the two courts. This gallery explores the museum’s interest in copying from its inception in 1851 to the present day. The last wall in the gallery looks at the value of copying in the 20th and 21st century and was inspired by the launching of the ReACH initiative in 2017. The agreement is an updated version of Henry Cole’s convention for the ‘International Convention for the Sharing and Promotion of Reproductions of Works of Art’ in 1867. The ‘Reproduction of Art and Cultural Heritage’ (ReACH) explores methods of reproducing, storing, and sharing works of art and cultural heritage in the digital age, and encourages the recording of fragile art and archaeology at risk from pollution, industrial growth and conflict. Objects on this wall explore the value of copying for preserving lost heritage and investigates the methods of replication available today.

During the research and development of the last wall display, the project team commissioned the RapidForm department at the Royal College of Art to produce 25 scans of objects from across the museum’s collection. Undertaking this project provided us with a better understanding of the technologies of 3D imaging, and gave us the opportunity to make new copies for the collection, bringing the story of copying at the V&A up to date.

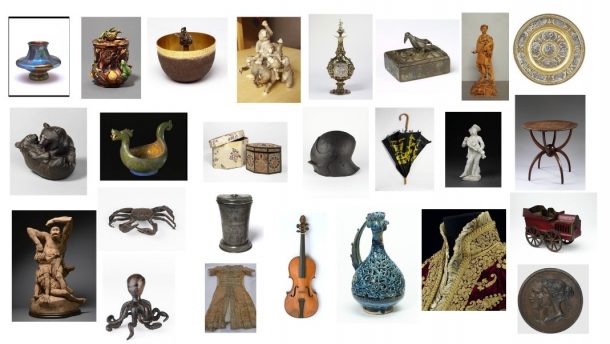

Choosing just 25 objects from the V&A’s enormous collection was incredibly tough, and so we reached out to colleagues across the museum for suggestions. Our remit was quite broad, and we asked for suggestions for objects that are visually interesting, would test the scanning equipment, could have a use for the learning team, were out of copyright, and practically were easy accessible for scanning. In addition, we asked for objects that we might learn more about from scanning, or that would enable us to show a part of the object that would not normally be seen by the public.

We came up with a very broad range of objects, and this ranged from an 18th century theatre costume and a bronze octopus, to a friction drive mechanism train from the Museum of Childhood and a Chinese protest umbrella. Unfortunately, not all of the scans were as successful as we hoped, as the complex components and materials presented a number of challenges to the equipment. However, some of the scans also came out far better than expected, and it was an exciting opportunity to learn more about how the technology would respond to a wide variety of objects. The second part of this blog series will describe the process of scanning an object, and how these scans were then turned into a 3D model.

The first of the 3D models produced is now available to view on the V&A’s Sketchfab page and the original is an electrotype copy of the Temperance Basin (more widely known as the Wimbledon Women’s Singles Trophy). A new physical copy of the basin, as well as a flask were also produced for permanent display in the new gallery. The basin is made from resin and was printed from the digital scan, and a second version was made as a touch object for the label rail beneath. The flask is a plaster powder print and reproduces a silver and glass flask bought by the Museum from the Parisian firm of Froment-Meurice at the Great Exhibition in 1851. The original has highly reflective surfaces which were difficult to capture in the scan and are not reproduced in this bright blue print.

This project was an exciting opportunity to explore the capabilities of 3D imaging today, and to investigate how the technology responded to a wide range of objects in the collection. The next post by the team from RapidForm at the RCA will discuss how the scanning was undertaken.