While researching for my post on John Henry Parker’s photographs of Rome, I came across the story of Charles Smeaton (1837–1868), a young Canadian photographer who collaborated with Parker to capture images of the Roman catacombs for the first time. I want to use this post to expand on his work in the catacombs and contribution to Parker’s project, and to show some more of his beautiful photographs.

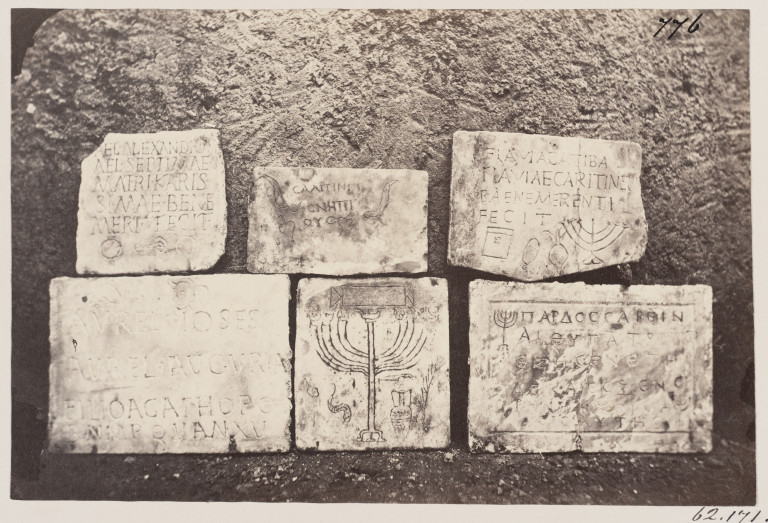

Smeaton was born in Quebec in around 1837. Nothing is known about his artistic training, but records show that in 1861 he opened Smeaton’s Photographic Gallery in Quebec, offering painted as well as photographic portraits. In the summer of 1866 he visited London, where he met the writer and antiquarian John Henry Parker. Parker was creating a photographic record of Rome, using mainly local Italian photographers, but had been unable to find a way to photograph the catacombs, with their limited space and absence of natural light. In Smeaton he found someone who had been experimenting with new forms of flash photography, and was confident of using magnesium flares to illuminate the catacombs. Parker and Smeaton did a test in Canterbury Cathedral and agreed to collaborate, starting in the 1866–7 season. Smeaton’s first Roman photographs were taken in the Vigna Randonini (previously known as the Jews’ Catacomb due to the Jewish iconography found inside).

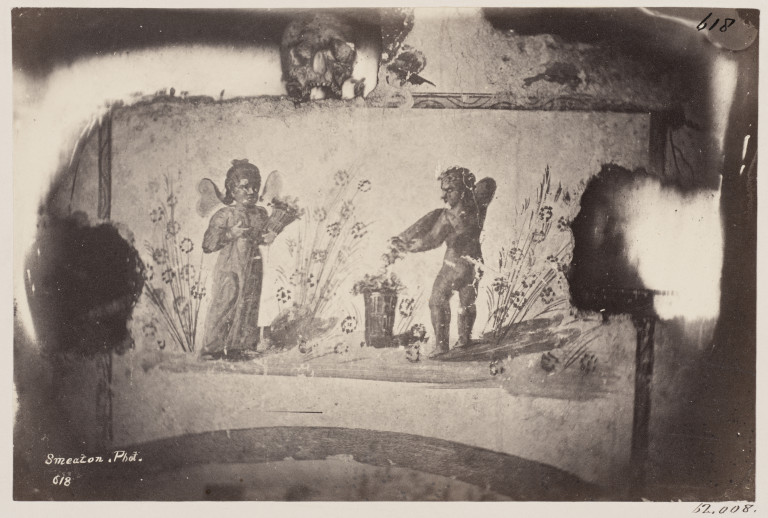

This is Smeaton’s first published photograph of the Roman catacombs.

The use of magnesium in photography was fairly new, although Smeaton was not the first to use it. In 1864 a chemist in Manchester, Edward Sonstadt, began to produce magnesium wire commercially. When held in a candle flame, the wire would ignite and burn with a brilliant white light. In a letter home, Smeaton describes carrying ‘coil upon coil of sunshine in the shape of magnesium wire’. He probably learnt of the technique from photographic journals, or from high-profile projects such as Charles Piazzi Smyth’s first photographs inside the Egyptian pyramids in 1865 (two of the cameras Piazzi Smyth used to photograph the pyramids are in the Royal Photographic Society collection – for details contact the Prints and Drawings Study Rooms).

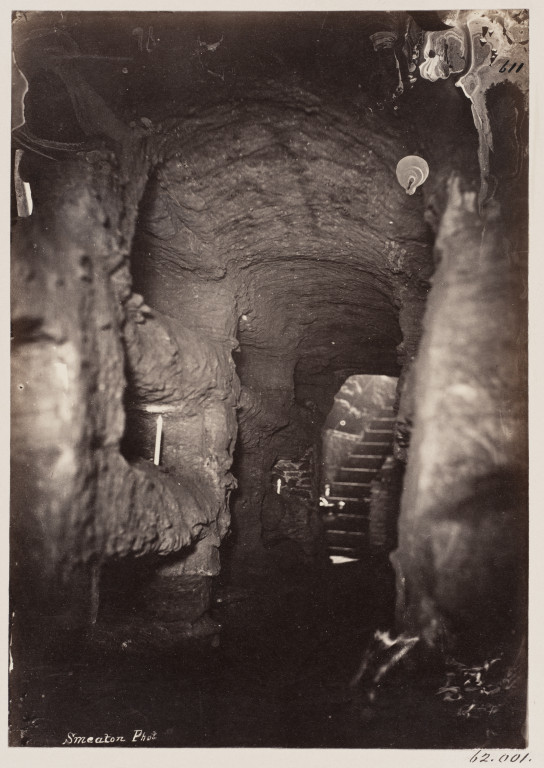

Working in the catacombs was not always pleasant: in his letter Smeaton describes ‘dismal dungeons’ and having to travel for half an hour through ‘tortuous passages’ to get to the chapel in the tomb of Priscilla. He also gives a vivid account of becoming lost in the tunnels, fearing that his light might run out, trapping him in the dark. The localised light source produced by the flash does give some of the photographs an eerie quality, with images seeming to emerge from the darkness.

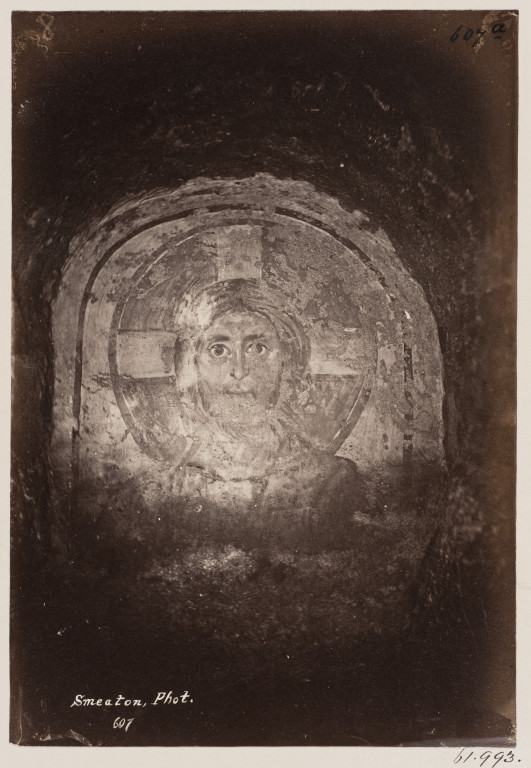

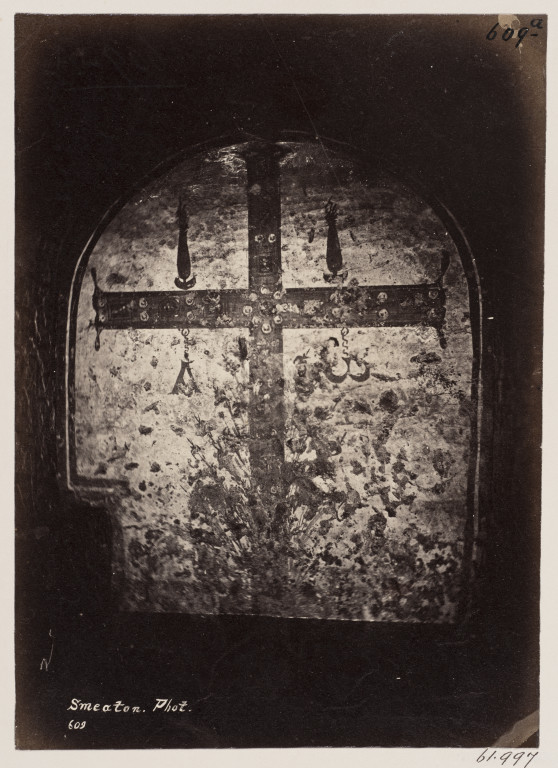

Some of the catacombs in Rome (underground burial chambers used by both Romans and Christians) had been known about for hundreds of years, but only reproduced in engravings, presumably from sketches produced quickly and in low light levels. Others had only recently been rediscovered, including the Jews’ Catacomb which was excavated in 1859. Smeaton recorded the interiors of at least seven catacombs, capturing images of architectural features, mosaics, sarcophagi and wall paintings.

The photographs of wall paintings were particularly significant to Parker, who was concerned with producing an accurate history of Rome and its archaeology. Clear photographic images gave him the ability to compare painting styles with dated examples, and although some of his conclusions are now known to be inaccurate, historians believe that he was correct in assigning later dates to many of the wall paintings.

Tragically, Smeaton died in the spring of 1868 of a virulent strain of malaria, the so-called ‘Roman fever’. He was aged just 31. A tombstone was erected in the Protestant cemetery in Rome ‘by his artist friends, in testimony of their esteem and regret’, and obituaries in the UK and Canada described him as ‘an artist of great promise’ and possessing ‘superior skill in photographic art’. His artistic legacy remains in a unique record of these hidden treasures of Rome. Even where catacombs have since been photographed in colour and higher definition, the photographs rarely capture the atmosphere of these early images.

I am indebted to John Osborne’s fascinating lecture at the British School at Rome (available to watch here), and the article ‘Un Canadien Errant’ by Andrea Terry and John Osborne, Canadian Art Review, Vol. 32, No. 1/2 (2007), pp. 94-106. References to Smeaton’s letters are taken from Osborne’s lecture.

Charles Smeaton was the younger cousin of my grandfather’s grandfather, also named Charles Smeaton, but of Kingston, Ontario. I have known the outlines of this story, but not these details, thank you very much.