In the beginning there was a gourd. The Gods made the sky and earth from the shell of the calabash, the flesh became the sun, and the seeds were scattered as the stars.

So goes traditional belief in Polynesia. Over 6,000 miles away in Laos, the Khmu people held that mankind was born from a gourd; after a destructive flood, the last two humans were tasked with repopulating the earth and the woman gave birth to a bottle-gourd, from which all of humanity emerged. For the indigenous Arawak peoples of South America, a gourd is the source of the sea; a man named Jaia buried his son in a gourd, and revisiting the body, realised the bones had turned into fish. When the gourd was broken by intruders, the oceans and sea creatures spilled forth.

Given the global popularity of gourds, it shouldn’t be too much of a surprise that gourds and gourd-inspired objects can be found in almost every V&A department. The object that first sparked my interest in squashes – and which eventually inspired this post – is held in the Indian Musical Instruments collection. It’s a pungi, or been, a wind instrument common in India, which I came across while working to audit and photograph the collection in preparation for its move to the V&A’s new Collections and Research Centre.

Often used in street performing, the pungi is fashioned from a hollow bottle gourd. The musician blows into the narrow end and uses two reed pipes inserted into the larger end to play the tune. When the gourd is blown into, the pipe with multiple holes – which is played much like a recorder – produces the melody, while the second pipe plays a single, drone note. Traditionally, the pungi was used by those musicians considered to be lower class, as the upper classes, such as Brahmin, were forbidden from playing most wind instruments.

After this initial find, I began to come across more and more instruments made from modified gourds in the stores. Some of my favourites were sarangi, stringed instruments played with a bow while sitting down, with the neck of the instrument leaning against the shoulder and the base resting in the lap. These can be highly decorative, such as the example shown below, and are often used as an accompaniment to singing, as they are said to be the instrument that can most closely mimic the human voice. Our website has an in-depth analysis of another of these instruments here, although this one, sadly, is gourd-less.

I also found that the sitars in the collection were frequently made from gourds. Sitars, like sarangis, are stringed instruments played sitting down, but are held diagonally across the body and played by plucking. The belly of a sitar can be made from a hollowed gourd, and there is often a second smaller gourd, attached part way up the wooden neck of the instrument, that acts as a resonator. The V&A has several beautifully decorated examples, intricately carved and often inlaid with ivory, some of which can be seen in the South Asia Galleries. Although an ancient instrument, the sitar was introduced to listeners outside of Asia most notably in the mid-20th century by the late great Ravi Shankar, an Indian musician and composer who performed at Woodstock and had a lasting influence on the Beatles’ George Harrison.

The use of gourds in musical instruments is not limited to Asia, as examples can also be found across Africa. In South Africa, an instrument called an umakhweyana is played in the Zulu community, often accompanied by singing. It is a large bow with a gourd resonator attached to the wooden strut, and the player holds it vertically while striking the string with a beater. Composer and musician Bavikile Ngema is a prominent umakhweyana player, and her energetic performance at the 2nd International Bow Music Conference can be seen here. Similar instruments are also played in Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe, and in Botswana, where it is called a segwane. Botswanan musical instruments also include the woso, a hand rattle made from a hollowed gourd filled with pebbles or hard seeds, and sometimes mounted on a stick. Woso are played with other instruments, and usually as an accompaniment to dancing. Similar rattles are found across much of West Africa with the name shekere, and in Latin America, where it is known as the chekeré or xequerê.

Gourds also have a less tangible place in the music world. The early 19th-century African American spiritual song Follow the Drinking Gourd has often been interpreted as a ‘map song’. Its lyrics are believed to have been a guide for those escaping slavery in the Southern States and moving north using the Underground Railroad – a network of safe-houses and secure routes. It includes the lines ‘Well the river bank makes a mighty good road / Dead trees will show you the way / Left foot, peg foot, travelling on / Follow the Drinking Gourd’. The Drinking Gourd is another name for the Plough (or Big Dipper) constellation which, if followed at night, would lead a traveller northwards to safety.

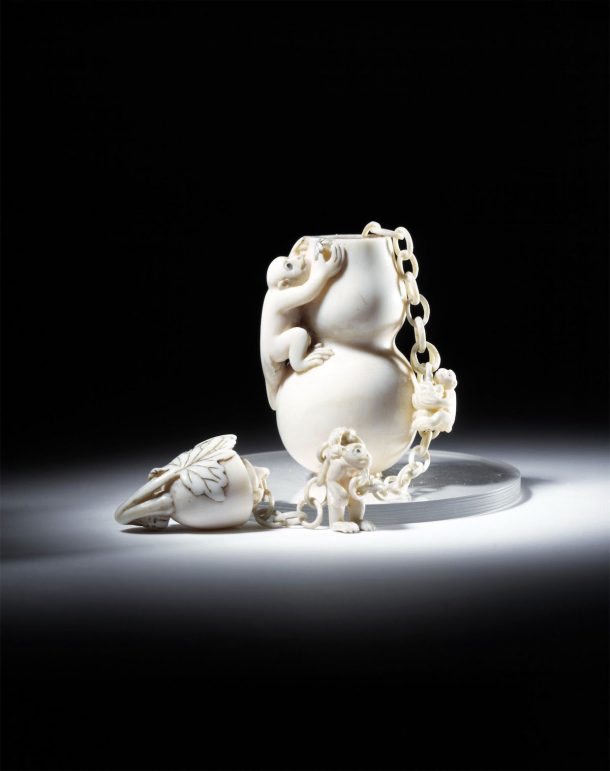

This Plough is not the only example of a cosmic calabash in history. Indeed, gourds are commonly considered to have mystical powers and often feature in rituals and ceremonies. In Japan, gourds are thought to have protective properties. Netsuke, the tokens worn as part of Japanese traditional dress, are often made either from a gourd or in the shape of a gourd. Because bottle gourds are believed to protect the wearer against falling over, this style is mainly worn by children and the elderly. For the same reason, geta – high platform shoes, examples of which can currently be seen in the V&A Kimono: Kyoto to Catwalk exhibition – are sometimes engraved with the sign of the gourd to prevent the wearer stumbling. More widely, gourds are used in fortune telling rituals in several cultures. For the Māori peoples of New Zealand, a gourd bowl known as Tipoki-o-rangi is believed to be the shrine of a powerful god. The base is filled with water, and the tohunga (priest) communicates with the deity, interpreting the responses from the agitation of the water. Female soothsayers from the Lenca people of Honduras and El Salvador tell the future by casting coloured beans from calabashes, and similar practices are performed in the Caribbean.

In Papua New Guinea, men from indigenous groups often wear a koteka, a dried and hollowed out gourd secured around the waist, to cover their genitals. These can be highly decorative and men tend to choose a gourd that fits in with the common koteka style of their community. Koteka have recently been in the limelight in a court case in Papua New Guinea, when Papuan independence activists were banned from wearing traditional dress during their hearing. Although the V&A has yet to acquire any penis sheaths, the British Museum has a well-endowed collection here.

From fancy phalluses to functional forms, gourds have also been used domestically for a variety of purposes. The Rappahannock people of North America made lamps from gourds, filling a gourd bowl with clay and adding a wick made of fatwood and pine. Peruvian fishermen use dried gourds as floats for their fishing nets, although commercial equivalents are becoming more common. Huqqa (or hookah/hukka) – pipes used for smoking – are common across Asia and the Middle East and can be made from gourds. In Iran, in particular, gourds were used to make the water reservoir which the smoke passes through before being inhaled. But perhaps the most common use of the gourd is as a drinking vessel. Gourd bottles are common across the globe, including in Africa, the Americas, and Asia. In Iberian and East Asian designs, the gourd is sometimes abandoned in favour of ceramics or glass, but the influence of the calabash lives on in the shape of the vessels.

502:1&2-1876 © Victoria and Albert Museum

Though at first they may seem humble, gourds are embedded throughout many cultures and have varied meanings. Next time you’re roaming the galleries of the V&A why not search for any overlooked gourds squashed away behind more glitzy displays and discover what secrets they may hold…

Hello Beth, Thank you for this wonderfully researched article. I have so enjoyed reading it and have been inspired to drop you a line to say “Thank You!” and when I’m at the V&A later this week, I’ll be on the gourd-trail.