The Victoria and Albert Museum is relocating its reserve collection from Blythe House to a new Collections and Research Centre in East London. As part of the preparations, we have been carrying out a survey of the paintings collection. Our initial findings indicated that we will need to treat around 200 paintings to make them safe to move: this will mainly involve fixing loose paint and preventive conservation – improving the way the paintings are fitted into their frames, and providing a backboard.

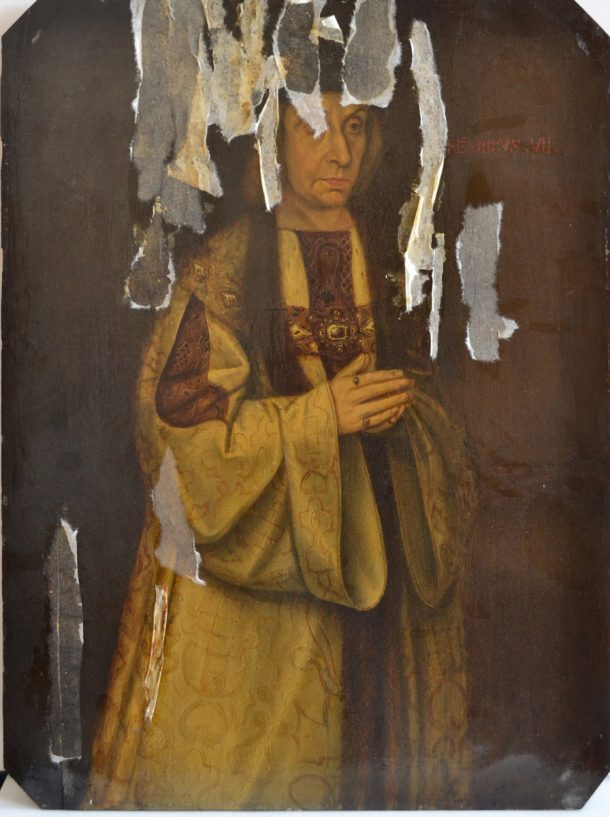

A month ago, I joined the Conservation Department at the V&A to support this venture by assessing and stabilising vulnerable paintings. As part of this project, I recently worked on the treatment of this portrait of Henry VII by an unknown painter.

Henry VII was born in 1447 and was crowned in 1485, the first monarch of the Tudor Dynasty (which lasted until 1603). The portrait was painted in oil on an oak panel – wooden panels were the standard support for oil paintings in Britain until later in the sixteenth century, when the use of canvas started to become popular. From the seventeenth century onwards, it became a matter of preference for the painter or the patron which support they chose, panel or canvas.

Wood is a hygroscopic material that absorbs and releases moisture according to the relative dampness or dryness of its environment. The way the wooden boards were sawn from the tree determines whether the board will stay flat or will tend to warp (radial cuts are more stable). When several boards are joined to create a panel, the individual boards will still swell and shrink separately according to the prevailing conditions.

In the 19th century a technique was developed to try and keep a panel that showed signs of warping flat. This painting shows an example of this. Called a cradle, the wooden lattice on the reverse has fixed battens in the grain direction, and thinner battens across the grain. Although they can be effective, they can’t prevent the swelling and shrinking of the original panel where it is exposed, which can result in a ‘washboard’ effect, as a warp develops in between the battens – and can also cause new splits, which has happened here.

You can see an example of this ‘washboard’ effect on another panel being examined prior to the move – Frans van Mieris the elder’s The Oyster Meal.

On top of the splits caused by the cradle, the painting had areas of facing (see detail below). The facing tissue paper was applied to prevent paint loss, as the tension and movement in the wooden panel caused the ground and paint layers to detach. Facing is usually considered a temporary measure to prevent paint loss (although this treatment dates from 1986!). It can cause more problems than it solves, as the paint still has be reattached to the panel, and the old facing can be difficult to remove.

To remove the facing paper from the detached paint I had to reactivate the glue holding it in place with warm deionised water, and peel off the paper while leaving the paint on the panel. To reattach the paint back on to the panel, I used sturgeon glue, and applied gentle pressure and heat.

After treatment, the painting is back in its frame. The frame is glazed and a backboard has been fitted, which means that the panel will now be buffered from changing relative humidity. By improving the panel’s immediate environment, we aim to prevent further problems – an act of preventive conservation. Henry is now in a stable and safe condition to travel, and will be awaiting your visit at the new V&A Collections and Research Centre when it opens.