Viewers of episode 4 of Secrets of the Museum might have noticed some conservation work on a very long and intriguing photograph. This post gives a little bit more about its background, and the amazing lengths taken by the museum to create copies of famous artworks.

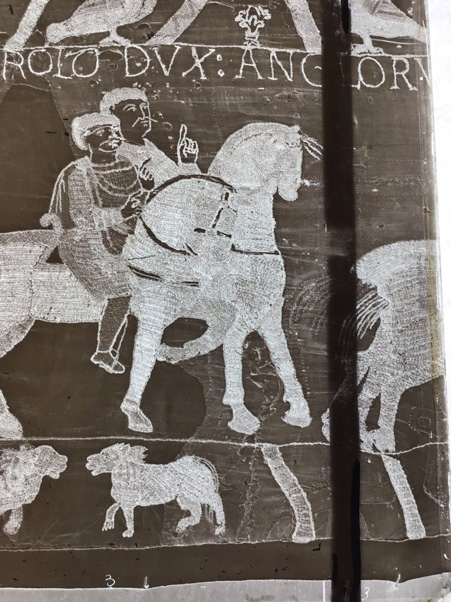

The Bayeux Tapestry is an embroidered strip of linen over 65 metres long that dates from around the 11th century. The embroidery depicts events leading up to the Battle of Hastings and the Norman Conquest of England in 1066. It has been on display in Bayeux, Normandy, since 1842. It is made up of eight conjoined sections of different lengths, and displays over 70 scenes, with decorative borders running along the top and bottom. This post is not about the tapestry itself though, but about an enormous photograph made of it.

The South Kensington Museum began thinking about making a photographic copy of the Bayeux Tapestry in 1869 (to add to their collection of replicas of famous art works). As a result of careful diplomatic negotiations, Joseph Cundall, the Victorian photographer, was given permission to photograph the entire Bayeux Tapestry in situ in 1872 for the Science and Art Department. Cundall arranged it through his company, and commissioned a photographer called Edward Dossetter to do the work. Dossetter went to Normandy between September and December of 1872 and made over 180 glass negatives, detailing each section of the tapestry.

Dossetter found various challenges in the task, as Frank Rede Fowke recounts in his book about the tapestries written in 1875:

The work was, however, attended with great difficulty, for, although the custodians finally permitted the removal of the glass, pane by pane, so as to free from distortion the portion of the work under manipulation, they would in nowise consent to the removal of the tapestry from its case. The tapestry is carried first round the exterior and then round the interior of a hollow parallelogram, and the room in which it shown is lighted by windows at the side and at one end, so that the difficulty of cross lights and dark corners had to be overcome as far as possible; nor this alone, for the brass joints of the glazing came continually in the way of the camera, and great credit is due to Mr Dossetter for the ingenious devices by which he successfully overcame the difficulties with which he had to contend.

Owing to the difficulties of manipulating a large camera in the comparatively small space of the chamber at Bayeux, the negatives first taken were but half the size of the original; from these transparencies were made, from which enlarged negatives were taken, and from these also the reduced negatives for the illustrations of this work were produced. It will be seen that besides the series here given two sets of large reproductions exist, one the full size of the original, and one half that size, both of which are published by the Arundel society.

Because of the unexpected cost of enlargement, Cundall had to go back to the Museum’s Director Henry Cole with a revised quote for the work, but it all took place successfully. The final process required 180 glass plates to make and is the largest photographic panorama made in the nineteenth century. The printing from the negatives was done using a photomechanical printing process called the Woodburytype, invented and patented by Walter Woodbury in 1864.

The process works as follows: a layer of gelatine is exposed to the sun with a negative on top. Where the light hits, the gelatine hardens and becomes insoluble. The areas under the darker parts of the negative stay soluble and can be washed away after the exposure, leaving a contoured mould. This mould is placed on a sheet of lead in a press and squeezed into the lead. The lead takes the impression from the mould, which is then used to create a metal plate that can be printed from.

After the photography and printing was complete, the next challenge was the colour. There was no colour photography in 1873, so Dossetter’s involved process resulted in a black and white image. Wanting their replica tapestry to be as accurate as possible, the museum sent one of the prizewinning students, Thomas Walter Wilson, from the National Art Training School (inside the museum at this point, and later renamed the Royal College of Art) to Normandy to copy the correct colours on to the photographs by hand.

The completed replica was finally exhibited at the International Exhibition of April 1873. After the exhibition closed, the replica was put on display in the Cast Courts at the South Kensington Museum (as the V&A was then known), on a rolling mechanism that people could scroll through.

The Arundel Society made six full-size copies in total, each of them hand-coloured, presumably using Walter Wilson’s first hand-coloured version as an ‘master copy’ to get the colours right for the rest. Two of the copies were acquired by the South Kensington Museum; one divided into 25 separate sections of 2.5 metres, and the other on a 65-metre roll. The shorter sections were lent out to art schools around the country for art lessons. The painted photographic copies were the model for a textile replica of the tapestry made in 1885 by a team of English women embroiderers under the direction of Elizabeth Wardle, and this replica is now on display in the Museum of Reading.

The Arundel Society photographs were offered for sale at the expensive price of £216 each. Considering the amount of labour and ingenuity that went into their making, the high price perhaps seems reasonable today. These replicas were the cutting edge of facsimile technology in the 1870s, and the story of their creation shows the same ambition and dedication to copies as the Cast Courts at the V&A, which opened a few years later.

There is more on the V&A’s relationship with the Bayeux Tapestry here.