Tools of the Trade

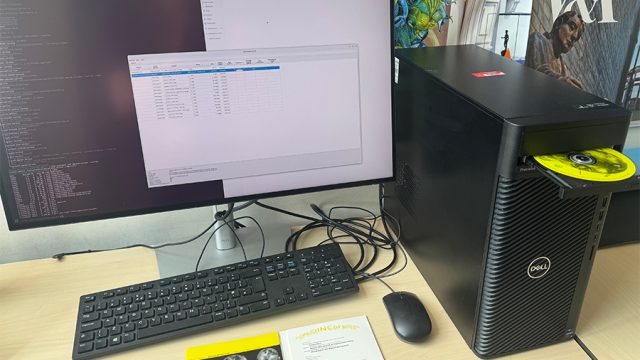

Here is a photograph of the tools I have brought with me for my month at the Metropolitan Museum of Art:

From its contents you may think that my profession leaned more towards that of the dental or woodworking industry than conservation but these really are some of the tools that may be required whilst conserving portrait miniatures.

Portrait miniatures are housed in lockets or cases. These can be ornate or simple; made from ivory, metals, (precious and otherwise) and sometimes bejewelled. They are not always contemporaneous – many have been replaced in later times. Some portrait miniature lockets/cases originally had lids. There are two such fine examples on display at the V&A: the Heneage Jewel contains a miniature of Elizabeth I by Tudor miniaturist and goldsmith, Nicholas Hilliard (1642-1619). The gold, enamelled locket is decorated with diamonds and rubies. The portrait miniature of Anne of Cleves by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/8-1543), is housed in an exquisite ivory box in the form of a rose with a screw on lid. The skill, craft and collaboration involved in manufacturing these objects is wondrous.

As I mentioned in my first posting, the world of miniatures is complex and releasing them from their lockets or cases can prove a challenge. Some of the tools seen here are used for such a purpose, such as the razor blade. Lockets may need to be opened for something as basic as cleaning the glass or more involved such as fixing flaking pigments. Some lockets are held together by small pins that secure the miniature’s housing and may need to be replaced once removed. The copper wire that you see in the photo is filed down to the appropriate size and shape to secure the locket parts back together again. The pin vice holds the wire firmly in place during the filing. The flat top cutter is used to get close enough to the locket edge so as to cut the pin and limit its length.

Grain tools are used to smooth and flatten out the end of the new pins. The goldbeaters’ skin is used to re-seal the miniature to the glass cover. It is so-called because goldbeaters used it to lay between leaves of metal whilst beating it into leaf. It is historically made from the outer membrane of ox intestine and for our purposes, coated with a size to make it sticky when wet.

Many of the tools you see come from specialist hardware shops that supply the watch and jewellery trade. These stores are located in Hatton Garden, London: an historic area linked to goldsmiths’ workshops for many centuries. However, the rodent-tooth burnisher was a gift made by paper conservation colleagues at the Met last year for a workshop on the conservation of portrait miniatures. It is a reproduction of the type of burnisher recommended by Nicholas Hilliard in his treatise, ‘The Arte of Limning’. Hilliard’s preference was a weasel or stoat’s tooth – small enough to burnish (smooth and shine) areas of silver or gold applied to the miniature.

Before attempting to open a miniature we investigate how the lockets or cases are put together – this is not always obvious. As far as I am concerned, opening miniatures is by far the most heart-stopping process of my training so far. It takes a lot of experience and some confidence to be able to get the miniatures out of their snug homes. It is also important to document how they came out so we know how to put them back together again.

What a fascinating world you live in.Thank you for sharing it in such an informative and interesting way.